3609 08-01 Another rival to her own son, destroyed

CAUTION: Contains themes of war oppression child and domestic abuse and bigotry some readers may find disturbing.

The evil began when we all began, so long ago. But the first time her little child felt it, was when they lost her. No—after Charlotte, too loving and good for the world she was brought into, was gone. Little Char had yet to put a name to it, but certainly felt it, and feared it as one fears all unknown dangers: instinctively. The instant she arrived, Kynborow, the new Lady Wrathdown, along with her sisters, and their mother Lady Parnell, falling like a dark cloak around Castle Shanganagh, so indecently soon after Charlotte disappeared. The green had barely yet begun to reclaim the soil over her grave.

The women of his new step-family smiled at little Char, so encouragingly. The smiles that reached their lips but not their brows. They seemed to read her secret heart and accept her, in a way even her own mother had not quite done. And yet some part of the child knew her mother’s love had been true, and her reservations sincere, whereas this affection was not. Kynborow had been introduced to Char’s father, Lord Wrathdown, by Sindonie, Kynborow’s older sister, a recent widow, who had been placed with them as Charlotte’s lady-in-waiting. The Lords of Skremen were another of the most powerful families in the Pale, and important allies to the Wrathdowns. Despite Sindonie’s undoubted competence and commitment to her duties, the then-Lady Wrathdown had not taken her on from personal friendship, and maintained a reserve towards her that something inside Char took note of.

Even before Char’s mother died, Sindonie had come across them: Char and her mother in their matching silk dresses, eating little honey-and-spice cakes Cook had helped Char to make and serve her mother. After looking thoughtful for a moment, Sindonie had smiled a secret little smile that was more predatory than friendly. Without understanding why, Char had known the smile was wrong. In fact, the knowledge had come not from the character of the smile, which was unfamiliar to the innocent child, but from the slight, sudden stiffening in her mother’s shoulders, a wordless signal that warned her child without either of them even being consciously aware of their primordial communication. It was good Charlotte who felt the first touch of evil upon her child, and transmitted the feeling as a warning to her daughter on a level deeper than breath itself.

Before that time, her father had paid little enough attention to Char. He had no interest in children, and children instinctively knew to stay away from him. He was not evil in the same way as Sindonie. Or perhaps, the operative fact was, his evil was not interested in Char yet; had not taken notice of her, and therefore had not reached out to ponder her yet. And in any event, a parent’s evil is always the hardest for a child to see. Thus it was Sindonie’s evil that first intruded upon Char’s awareness, much like the fearful shiver of a night pedestrian hurrying past a darkened alley.

Though Char didn’t know it, it was Sindonie who had first whispered “popinjay,” a term she had picked up on her travels to London, to the senior Roland, a word the Lord Wrathdown soon began associating with, and using to refer to, his youngest child.

It was not until her mother was gone that the full weight of Sindonie’s and the Skremen family’s insidious evil fell upon Char; or that Char’s innocent young mind grasped what it was faced with. Sindonie, in her role as one of Charlotte’s ladies, made it her special mission to pay attention to Charlotte’s three surviving children, and care for her youngest. Char’s surviving two older brothers (their parents having lost four children here on the rough-and-rugged edge of the Kingdom) were Young Roland and Rash Henry. They had taken a liking to Sindonie from the first time they set eyes upon her; a liking Sindonie carefully encouraged them and everyone else to accept was a natural fondness for the mother of their friend Oliver, a difficult but talented young man about halfway between Roland and Henry in age, who became inseparable from Rash Henry almost from the beginning.

The first artificial blush on Char’s face was put there by Miss Sindonie, to give her wan, drawn cheeks a bit of color for her mother’s funeral. It was not, Miss Sindonie emphasized, ladies’ makeup; but an herbal tincture to restore her health. An herbalist herself, Miss Sindonie stood out from her peers (including her own sisters) by her own refusal to wear makeup, which she confided to Char was “compounded by charlatans” from metals and poisons that threw the body’s humors completely out of balance. Char had not minded the medicine, and indeed would not have noticed how it complimented her delicate features unless Miss Sindonie had taken special care to point it out that evening, encouraging her to refresh it the next morning, and until she started feeling herself again. Each day, she carefully helped Char with the tincture in the morning, encouraging her with how much better it would make her feel, and how much easier her day would be with the confidence it inspired, until Char would have felt misgivings if she skipped it. Also, when her father was not around—which was usually the case—Miss Sindonie put Char in one of the dresses that matched her mothers’, and even let her and Cook make and serve honey-and-spice cakes to Sindonie and Edith, listening patiently and encouraging Char to remember how close she felt to her mother, reminding her how special it felt to dress and look like her.

Miss Sindonie was not one to spare the rod, on Oliver or on Rash Henry or Char, a nickname she herself bestowed on the girl to her face (restricting her own use of the term “Popinjay” to her private conversations with Roland and her own family). But she was very attentive and even caring, even if a wall of ice surrounded her that never quite melted to anyone except, on the odd occasion, her own son. Char loved her new nickname, loved the way it sounded and made her feel, a proper girl’s name like her mother Charlotte’s. And although a part of her remained wary of Miss Sindonie, it sank into subconsciousness because what Miss Sindonie showed her—unlike other adults, who were too busy to do so—was attention and effort, not siblings but certainly cousins of affection.

And Char sensed a related truth: That Miss Sindonie was genuinely interested in her, in her development, in shaping and influencing her, in making sure she learned certain things properly, like the honey-and-spice cakes: more than simply mixing and heating the ingredients, but how to flavor them and encourage them with your voice and hands so they made the world a little brighter, the plants greener, and the sky bluer. Some part of Char knew the delight and pride in her shown by Miss Sindonie when Char cooked and served well was genuine, too.

The first time Char met Miss Sindonie’s sisters and mother was about a month after Charlotte Wrathdown’s funeral, at Kynborow’s wedding to her father Roland. They giggled and complemented Char and Sindonie on the fine silk, elaborate detailing, and decorations on Char’s gown, and how grown-up she looked compared with the other children in their simple, undifferentiating gowns. Lady Parnell, with a smirk Char did not quite like, even pinched Char’s cheek and praised how healthy she looked, pausing and emphasizing the word “healthy” with a widening of her cold smile. Char shuddered, that wintry expression so familiar from Miss Sindonie. With Miss Sindonie, she had somehow gotten so used to it it didn’t register any more; but recognizing the same expression coming from Lady Parnell and her other daughters struck her all over again, as hard as it had the first time she’d seen it.

Lord Roland Wrathdown treated Char with contempt and a simmering anger that might have been higher since Charlotte’s death, but were not categorically new. Something even more hostile and cold had passed across Lord Roland’s features when he caught sight of Char at the wedding, but not so unusual it struck Char as odd; and the fact he ignored Char after that, even excluding her from the wedding party, was thoroughly in keeping with his past treatment.

It was not for six months that the unease Char felt for her father’s treatment—an unease she didn’t really distinguish from the overwhelming misery of losing her mother—crystalized into horror, damage, and more loss on Char’s part. She was too young to even recognize that dread had been in anticipation of something like the storm that finally broke that day in the chapel.

Mistress Kynborow—Char could not even think of her yet as Lady Wrathdown—disappeared with Lord Wrathdown for a fortnight after the wedding, not to be disturbed (as if Char would want to see either of them). Soon after they resurfaced, Lady Wrathdown commenced holding court on a more-or-less daily basis with the other gentle women of Wrathdown who lived close enough to Shanganagh Castle they felt safe traveling to it. Predictably, most women who could persuade themselves to feel safe, came to mingle with the Baroness regardless of the actual risk.

Their daughters over seven, and well-behaved children like Char and a couple of the girls, were allowed, and therefore expected, to join them for embroidery, games, and of course prayers, when not in the castle’s Dame School with Miss Sindonie, who had taken it over upon her sister’s arrival.

“I miss my father,” Edith admitted wistfully, at one such gathering, about six months after the wedding. “And I worry about him.” She had moved to an arrowslit on the South wall, which served as one of the chapel’s windows, and was peering down at the Bray Road below trying to see the horsemen they had all heard clattering past. The arrow slits, being cruciform, were in a way quite appropriate for the chapel, which was being used as a makeshift classroom for the petty school students aged 4-7 when it wasn’t being used for Lady Wrathdown to hold court.

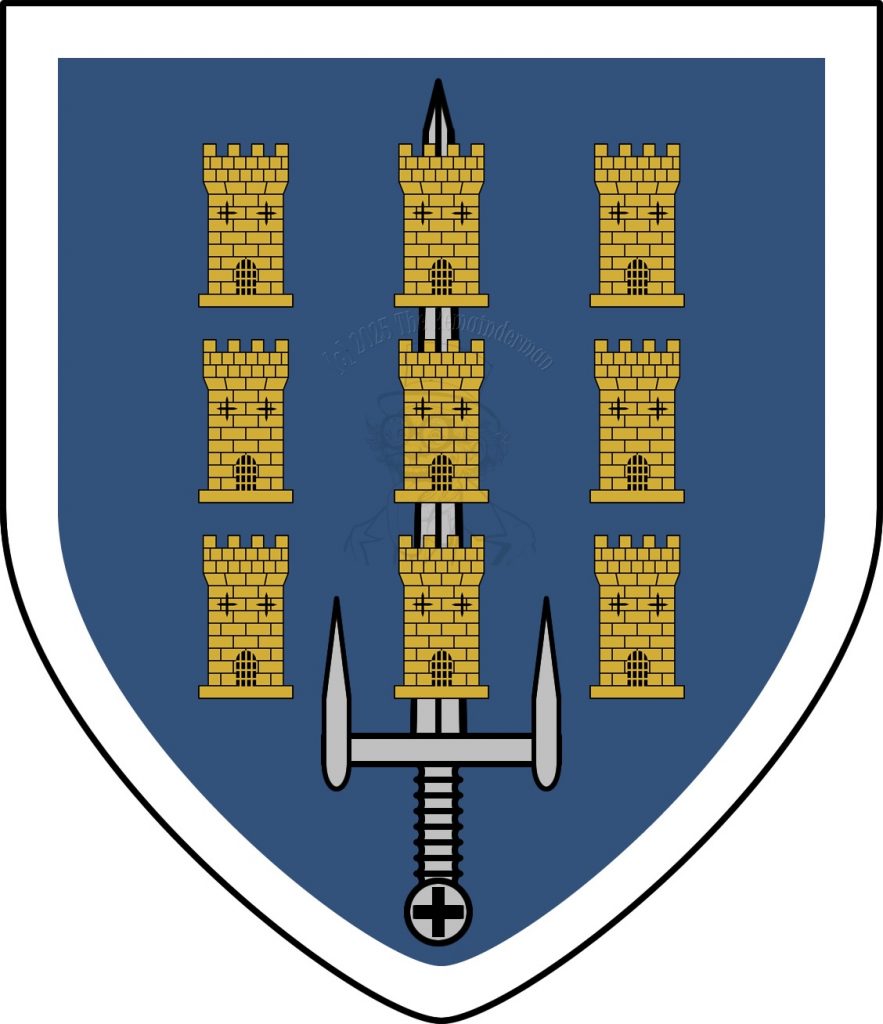

Edith and her friend Char were embroidering their Lord’s banner together, working on a magnificent bolt of blue silk from China. Char was using fine golden thread to embroider a castle, one of nine on Baron Wrathdown’s coat of arms, while Edith was using fine silver thread to embroider the raised sword beneath the three castles in the center column. As they did so, Edith’s mother, Char’s stepmother, and their teacher SIndonie, were gossiping and brushing the girls’ long hair.

Char was sitting with one thigh over his stepmother’s leg and her bottom on Miss Sindonie’s lap, as she had been for most of the morning. The women liked to keep her close, their hands on her waist or hips, even at an age when other children were beginning to separate a bit more from their parents. Lady Wrathdown was so hugely pregnant, her lap could no longer accommodate Char. They said her baby had grown quickly and could come any day now. When Friar Hugh was teaching, Miss Sindonie often acted as surrogate stepmother.

The other ladies of the half-serjeanty sat around them with their daughters, working on projects while the children’s tutor, Friar Hugh, an Augustinian who assisted Sindonie with the children’s Latin and religious studies when he was in Wrathdown, wrang his hands and tried to decide how quickly he could excuse himself to chase down the rest of his students—the women’s sons, the girls’ brothers—who had bolted excitedly from their lessons to see what all the racket was about. The clergyman couldn’t quite mind their absence for a bit; they bleated and fidgeted like excited goats. Girls might not have the intellect for learning, but they certainly had the superior manner.

“I want my father to come back,” Edith frowned.

Char responded matter-of-factly, “I don’t,” provoking a dutiful tutting sound of disapproval from her stepmother and step-aunt, and a satisfied smirk from her step-grandmother, Lady Parnell.

“Your fathers’ work is important!” Friar Hugh reminded both of them, presumably intending to comfort or reconcile them to the situation in some way, but sounding more like he didn’t want anyone to overhear them saying such things, deciding to bolster his position with an unnecessary and arguably pompous lecture: “All Ireland is divided into three parts: Gaelic, Norman, and English. The wild Irish savages have overrun most of the North and West, and unfortunately, the wilderness just to the South of us, while the King has been focused elsewhere. Most of the ancient Norman lords, themselves bastardized by their time in this godforsaken land—”

“Sir!” Miss Kynborow laughed, scandalized, pausing in her hair-brushing to put her hands over Char’s ears. Her ladies laughed with her; and their daughters, according to their age and disposition, either smiled uncertainly or looked nervous. “We are the source of civilization here. We must set an example!”

“Quite right, Lady Wrathdown!” Friar Hugh agreed, looking flustered and almost tripping over his words. “The Norman Earls beyond the Pale—they’ve become more Irishthan the Irish, lacking all appropriate devotion to Ireland’s proper Lord, our blessed King Henry, designated to rule here by the Pope himself! They aren’t reivan’ and raidin’ us like the Irish sinners, but they aren’t loyal, either! Only we, the good Kings’ men of the Pale, the land behind the wall, the Lordship of Ireland, defended by your fathers, are the lone outpost of true English culture here! Your fathers’ work defending the Church and law and order is the work of King and Christ, children!”

“Yes, sir,” the children dutifully responded, exchanging meaningful looks expressing their fervent hope his speech would not inspire another lengthy prayer begging God to strengthen their fathers’ hands against the murderous clans to the South.

But Friar Hugh was going in another direction, shaking his head, lost in thought: “Beyond the Pale it’s all chaos and cannibals—”

Edith gasped excitedly. “Cannibals!”

“Thank you, sir,” Lady Kynborow gave their priest a significant look. “I think that’s enough on that topic.”

Friar Hugh turned bright red and shuffled nervously. “Yes of course, Lady Kynborow. I just meant, they’re barbaric! They don’t even wear shoes!”

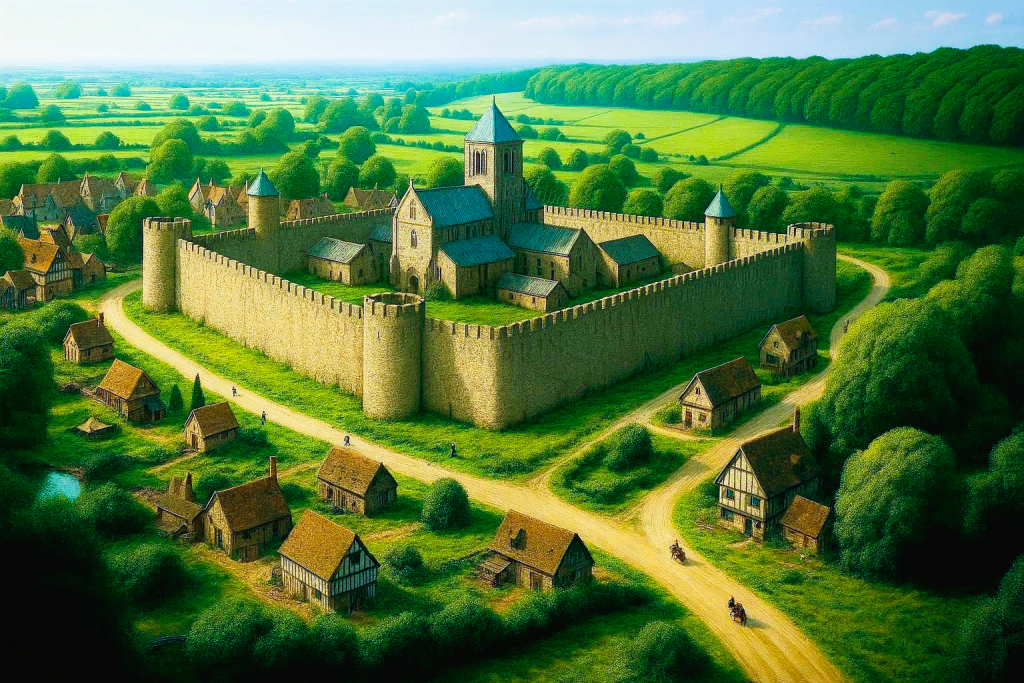

The girls giggled, while Lady Kynborow’s mother, Lady Parnell, muttered: “No need to mind your language on our account, Father. There’s not a child in Shanganagh Castle left with tender ears,” provoking more giggling from the older girls. Wrathdown was shaped and practically defined by its role defending Dublin against perennial Irish raids from the Wicklow Mountain country. It had a rough-and-ready martial character that preceded, but certainly could not eclipse, its present Lord, who practically personified the Norman warrior ethos of old. The force of his personality had imprinted itself on every male in the castle and the countryside alike, and even attracted a number of rugged young adventurers from England and elsewhere to try their hand against the Irish. It helped in recruiting that there were more manors than knights here on the border, available to anyone with the wit and strength to secure a hold for themselves in the name of the Pope and the King. Even in a man’s world, the Irish frontier was man’s country in 1516, with women living on the margins of daily life.

“Mother!” Lady Kynborow repressed a smile.

“Don’t pretend otherwise. Char’s muckspout father—”

As if to make her point, at that very moment Baron Roland, Lord of the Half-Serjeanty of Wrathdown himself, threw the door open hard enough for its hinges to rattle and the latch to chip off a bit of stone from the wall of the small castle. Very much a Marcher Lord, wielding a real and direct military power that most English barons lacked to prosecute his King’s war, the Baron maintained nine front-line castles shielding Dublin from the depredations of the Irish natives to the South, all connected by earthen barrier walls running from the Irish Sea at Wrathdown Castle to the border with Uppercross past Templeogue Castle. They imposed a significant burden on the modest revenues of the Serjeanty, even with the subsidies he received from the viceroy’s Dublin Castle administration.

So it was hardly surprising the castles were compact, efficient, and coarse, combining the functions of defense with those of daily life. The chapel, occupying the third floor of the small castle, was used for everything from mass to feasts to rare tax-exempt markets and classes like this one, especially in warmer months when the welcome light and fresh air provided by the third-story arrowslits compared most favorably with their drawbacks in winter, a time when they were usually filled with loose bricks. The ground floor was the great hall where they slept and ate and even cooked; and the second floor, Lord Wrathdown’s private chambers, storerooms, and utility rooms.

The Baron’s impromptu retinue, the excited boys of the castle Friar Hugh had been fretting over, swarmed back into the room, swirling around the Baron and his companions like a Huntsman’s dogs howling and barking in excitement while dodging the hooves of angry stallions.

“God’s light! Finally! Here you all are. I practically ransacked the castle. What divine office are we celebrating mid-afternoon?! We thought the damned savages must have taken the lot of you!”

Lady Parnell directed a look at her daughter as if the obvious had been revealed, but otherwise there was little enough room for anyone else when Lord Wrathdown took the stage. Stinking of smoke, sweat, and offal, his clothing and skin were stained and spattered reddish-brown with dried blood, the clean patches of his head and chest revealing where he had removed his helmet and cuirass upon entering the castle.

“Papa!” Edith cried as her father, Sir Ambrose, entered behind his Lord, thwarted in her attempt to hurry to him by her mother, who hugged her tightly. Sir Ambrose was half-leading, half-pulling a copper-headed, dazed-looking barefoot boy of about 5 or 6—Char’s age—in a gown behind him. Both of them were as bloodstained and filthy as the Baron; and the boy’s air of detachment and lack of focus were only reinforced by the contrast he made with the intensely involved and overstimulated castle children. Edith’s father smiled encouragingly at her, but with a gently raised palm, urging her to wait. No adult in the room imagined it a good idea to compete with their Baron for attention. And in fairness, the man was larger than life, well over six feet tall with broad shoulders, strong arms, and an impressively-long beard demonstrating his virility. His personality was as loud and brash as his speech. Edith’s father could not have competed with that if he’d been of a mind to; and he was far too sensible to have any such thing in mind. Only three of Roland’s half-brothers, half of the children of his father’s first wife, had survived childhood. One, it was rumored, had gotten in the way of Roland’s ambition and died gruesomely. A second, eager to stay out of his way, had joined the church. The third, and eldest, was an Earl of the family’s main estates in England, and doubtless hoped Roland’s inheritance in the Pale would keep him too busy to come after him.

The last member of their party to enter, marked with the same stains and smells as the other three, was Young Roland, the Baron’s firstborn son, unmistakably of a piece with the Duke himself, Char, and Rash Henry (wherever he was): Every member of the family’s hair, on both sides, shone a blazing yellow-gold. Theirs was the hair of lions, not just yellowish, but a strong, saturated hue that made other shades of yellow look washed-out or dirty.

“Yesterday was a magnificent day! We caught half the damned O’Tooles, and the O’Byrnes too! Out looting and burning in Bray and Shankhill. I collected six Irish heads!” he roared proudly, gesturing impatiently at his son. “Show ‘em, lad!”

Char and the ladies cried out and recoiled in horror as Young Roland, grinning proudly, held up two strings of four heads each, with their hair braided and bound together with rope like obscene cloves of garlic. “I got two of my own, Stepmother!” he boasted enthusiastically, smiling so proudly she felt obliged to smile back at him with the same enthusiasm a peasant woman would greet a housecat returning with a dead mouse in its jaws.

“That’s nice, dear!” she applauded, doing her best and elbowing Char, who, jaw set and arms crossed, ignored her. “Isn’t that nice?” And when ignored by Char, pressed her husband: “God bless you on your victory, my Lord!”

He rumbled angrily. “More of a draw. But it was a glorious, unholy bloodbath! The manor of Raheen-a-Cluig’s a goner. The men of the village were strung up and cut up into ribbons, and the women and children who weren’t raped and butchered were taken by the O’Byrnes.” Neither Lady Kynborow nor anyone else in the room thought about chiding the Baron for his language. “Lost for good up in the mountains. But it wasn’t all bad, we left the dirt soaked with their tainted Irish blood, and caught a few slaves for the lead mines. Oh! And here, give me the lad!” Roland gestured to Ambrose, who gently nudged the dazed boy toward his Lord, who in turn, seized his arm and yanked him forward. “My knight and his wife were dismembered with the rest of the manor in most grisly fashion, must have screamed for hours! But this one hid. Or, more like, the Irish just didn’t want anything to do with this odd fellow.” Roland shook him slightly for emphasis to make sure Parnell and Kynborow understood who he was referring to. “Their son and heir. He’s my ward now, and in addition to bringing me his rents, the parish priest in Bray says he’s a sage in the making. That note’s for you, Father,” Roland jabbed his finger toward a reddened scrap of paper pinned to the collar of the boy’s robe. “He’ll be a perfect tutoring companion for that worthless son of mine, who wasn’t with the rest of my wild dogs—” he gestured vaguely towards the boys tripping over themselves to follow him around. “Where is that Popinjay?”

Something in Kynborow’s guilty expression must have alerted the Baron to the truth because his eyes widened and bulged out, his face turned a mottled purple, and he bellowed: “My son?! You’ve got my son there brushing his hair?”

Young Roland guffawed nastily, and even the unfortunate orphan blinked twice, the closest thing to an expression of any kind, facial or verbal, he seemed able to muster, as Lord Wrathdown dumped him unceremoniously onto an empty pew and barked “Shut up!” to his eldest. Nobody else in the room required such a caution; not one of them, not even the stupidest of the castle boys, dared meet the Baron’s eyes, let alone make any sound that might catch his attention. “He’s SEWING?!?! MY SON is SEWING with the women of the Castle instead of playing with his friends?!”

“These are my friends!” Char murmured, ducking his head and shrinking back into Kynborow even as he spoke. “not them!”

“Please, my Lord!” Kynborow—having no way to avoid her husband’s attention—pleaded. Because she and Miss Sindonie were behind her, Char couldn’t see their expressions; and the Baron was too distracted to pay any attention to them. But although Kynborow was doing an impressive job keeping her face in character with a distressed woman, every bit as well as she was going to lie, Sindonie’s face betrayed the faintest hint of a smile despite her best efforts to suppress it. “We’ll bring her—I mean, him—along, but we want to keep him as his mother made him for a little while longer, to comfort him. He’s only lost his mother last winter—we want to give him some time to recover and grieve before we bring him into our family!”

“SEWING AND PLAYING WITH GIRLS?! The Baron Wrathdown’s SON?! NEVER!!! NOT FOR ONE SECOND MORE!!!” Baron Roland roared, his face turning purple and wrathful while veins bulged alarmingly from the sides of his neck. “Clearly he’s better off with her dead!”

His attention was distracted back to his son as Char burst out crying: “I’d only be better off with you dead!”

“HOW DARE YOU?!?! Not just a woman, then, but your sex warped back again into a shrew?! What’s wrong with you?!” Lord Wrathdown thundered incredulously. “God, and therefore Wrathdown” (it was unclear here whether, having taken the Lord’s name in vain, he was referring to himself as the Baron, or taking it upon himself to speak for the entire half-serjeanty) “will not tolerate such an abomination as a baedling! I’ve got to STOP THE ROT for the sake of our family!” Roland growled again, wading forward to tear the child forcibly away from his stepmother, throwing him down over a pew and thrashing him with the flat of his blade—cleaner than his own flask, and doubtless the only thing beside his horse and other weapons Lord Wrathdown had made sure were tended after the battle—while the Skremens wept crocodile tears,. Miss Sindonie, her eyes glittering cruelly, held Kynborow back, and every other woman in the chapel started shrieking. Even Friar Hugh murmured nearly-audible protests, waving his hands ineffectively as he considered whether and how he dare intervene. Continuing to wallop mercilessly on poor Charles’s bottom, the Baron continued his diatribe: “We’ve got to get you away from the evil influence of these damned women! You’ve clearly been coddled and indulged by women long enough!”

“No, please!” Kynborow wept convincingly, as the Baron’s arm rose and fell, rose and fell, over and over again, on his bawling, kicking, crying child. “Please, Roland! Surely that’s enough?!”

“NOTHING’S enough for a son of Roland Wrathdown who sews and brushes his hair like a woman!” It almost sounded like Lord Wrathdown was weeping with his frustration and rage, his eyes filled with the same aubergine fury that stained his face and every inch of visible skin, as spittle flew out of his mouth. “No son of Roland Wrathdown plays with girls instead of boys! I thank the lord he gave me six my other good and manly boys before this one was sent from hell to disgrace us!”

Lady Parnell and several other women were trying to restrain the hysterical Kynborow who was screaming and crying and trying desperately to protect her stepson, while Sir Ambrose and Friar Hugh edged nearer to the Baron with their hands raised placatingly, ineffectively trying to encourage the Baron to stop. Behind them, the red-haired boy sat still and slumped where the Baron had dumped him, staring listlessly toward the altar with his unfocused, haunted sapphire eyes, showing no interest in—or even awareness of—the maelstrom around him.

“And YOU!” He jabbed his finger towards Lady Parnell and her daughters, startling them. “You can stay to help my Kynborow with the birth but as soon as my boy is born, YOU—” he poked his finger into Sindonie’s shoulder, “and YOU—” he pointed his finger rudely at Lady Parnell, “AND you!” stabbing toward the youngest sister, Thomasin, “Return to your own Lord in Skremen! I won’t have you poisoning my next boy!”

“What if it’s a girl?” Kynborow asked, perhaps before thinking better of it, but only thinking whether they might be allowed to stay in that circumstance, instead of leaving her here alone in this masculine demesne so far from Skremen.

“Then I’ll blame YOU for breaking my perfect record of boys!” Roland roared, so focused on his own concerns he couldn’t imagine any of his wife’s.

“If I thought he was man enough, I’d squire him to Lord Nethercross, he’s a hard man! But this prating grovelsimp is already RUINED!” Lord Wrathdown’s eyes widened, as he hit upon the solution to his remaining problem: “None of our family have gone for the church in generations—only our money. It’s time to recoup on that investment! I’ll send him, to live among men, and eradicate every bit of female weakness! AND he won’t corrupt our blood by breeding!”

“We would be honored,” Friar Hugh assured him eagerly. “In a year or two, when he’s ready—”

“ARE YOU LISTENING TO ME?!” As if any of them could fail to do so. “Not a year or two. NOW! Before he becomes a full-on eunuch!” Lord Wrathdown growled dangerously, turning his attention to the terrified Friar Hugh. “Get away from me, you worthless fopdoodle!” The Baron struggled to find words, flinging his bawling son away from him without even letting him catch his balance. “I can’t stand to touch you right now!” Instead of walking, Char careened several feet across the stones and fell onto the lap of the orphaned boy, who absentmindedly folded his arms over Char and began rocking him gently and patting his back, repeating “there, there” without even looking down in a mechanistic way that was much creepier than his dazed silence had been. Char shrieked and wailed, burying his head in the boy’s lap and hugging him tightly back, kicking his own legs in a desperate gesture to discharge the intense emotions and physical pain that were overwhelming him, threatening to swallow him whole.

Lord Wrathdown looked askance at the orphan a moment more, then shook his head. “Smart or no, there’s something badly wrong with that one. But that makes two of them. And they seem well-matched.” Nodding and shrugging, he looked at Sir Ambrose. “And at least he is male!”

“Certainly true, Lord Roland,” Sir Ambrose agreed. “A perfect companion!”

“You’ll take them both, father!” Lord Roland barked, deciding it on the spot. “Today! Take him to that—choir school I sponsor at Christ’s Church!”

“Oh, good, they can… sing, Your Lordship?” Friar Hugh asked, sounding as reasonable as a canon lawyer but cringing all the same hoping the question would not provoke Lord Roland.

Apparently Friar Hugh had no such luck in store. “DOES IT MATTER?!” Lord Roland demanded loudly.

“Not at all,” Friar Hugh assured him, backpedaling, “only, it’s just, Father Luke, the Choirmaster, is quite the martinet, he runs the choir as a tight ship, likes to try out and hand-pick the boys himself—” Everyone other than the Baron could see how conflicted and agitated Friar Hugh was, swallowing and practically wringing his hands with anxiety as he considered his position, how to explain his actions to his superiors if he turned up with two underaged no-talent boys, trying to insert them into another friar’s choir and school when doing so would interfere with the progress of the rest of the class.

It would surprise exactly no one in Castle Shanganagh to learn Father Luke had been the newest and lowest-ranking member of his order in Ireland when he was assigned as the tutor to the nobility and gentry here.

Even as Roland began turning his head to fix his eyes on Friar Hugh, Friar Hugh achieved the breakthrough he urgently required, bringing his deliberations to their speedy and vitally necessary end, babbling: “Actually… not at all. Of course not. It doesn’t matter at all, Your Lordship. Everyone can sing! I mean, everyone has a voice. And of course, Father Luke will be so thrilled to have another of y—to have such a high-bred young man and his—er—” Luke had no idea what to say about the orphaned boy, knowing only that by birth, he was a member of the gentry. But after all, that was probably enough: “His gentle companion, er—ah, thank you, My Lord, thank you for—for entrusting them to us.”

“That’s better,” The Baron allowed, his eyes widening with pleasure to see the unmistakable lust on at least Kynborow’s—and Sidonie’s—faces. Kynborow was still crying, speaking no words but now begging him for something different with her eyes.

“Fuck!” the Baron rumbled, adjusting his codpiece. “After yesterday’s battle… and you’re carrying our little one…. This is my point! Your sympathies are misplaced! A woman wants a real man! Coddling the little ponce won’t serve him in the long run. Come on, we want our child to be vigorous and healthy!” he urged her, pulling Kynborow against him, rubbing his crotch against hers, and stroking her breast without a thought to subtlety. “Ah… Help your sister, Sindonie,” he breathed raggedly, eyeing his sister-in-law, before pulling his attention back to his wife and his wife towards the stairs to their bedroom below. “It’s practically a duty! Come, welcome your Lord home from battle properly!”

Literature Section “08-01R REWRITE The Pustlular Bloom of Evil”—more material available at TheRemainderman.com—Part 1 of Chapter Eight, “The Wild, Wild West”—about 2134 words [5450-3316=2134 additional words]—Accompanying Images: 3605-3616—Published 2025-12-30—©2025 The Remainderman. This is a work of fiction, not a book of suggestions. It’s filled with fantasies, stupid choices, evil, harm, danger, death, mythical creatures, idiots, and criminals. Don’t try, believe, or imitate them or any of it.