PREVIOUSLY: By trickery and deadly threat, eight-year-old Pen has agreed to help the succubae until dawn, as they raid the Venetian capitol late on a storm-torn night of floods, seeking to destroy what the Venetian spy service has learned about the succubae and to release an imprisoned grandfather and a young girl accused of witchraft. Pen has now been geased to compel him and spelled to trust Channah and believe she is by his side. NOW:

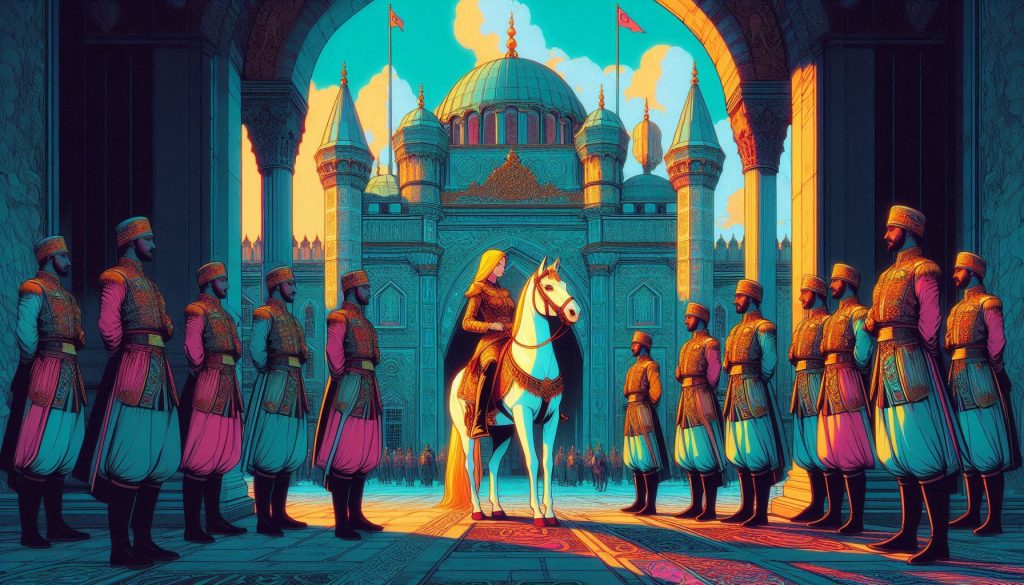

Pen, bound as a safety net by a leash attached to a harness, and following Chava’s reasonable suggestions and whispers, crossed the hallowed space, picked the lock (under a minor delusion that he was simply unlocking a difficult lock using several keys at once), opened the door of the archive, and crept inside to access the secret files of Europe’s, and perhaps the world’s, most-extensive and most-advanced spy agency: The Council of Ten of the Serenissima.

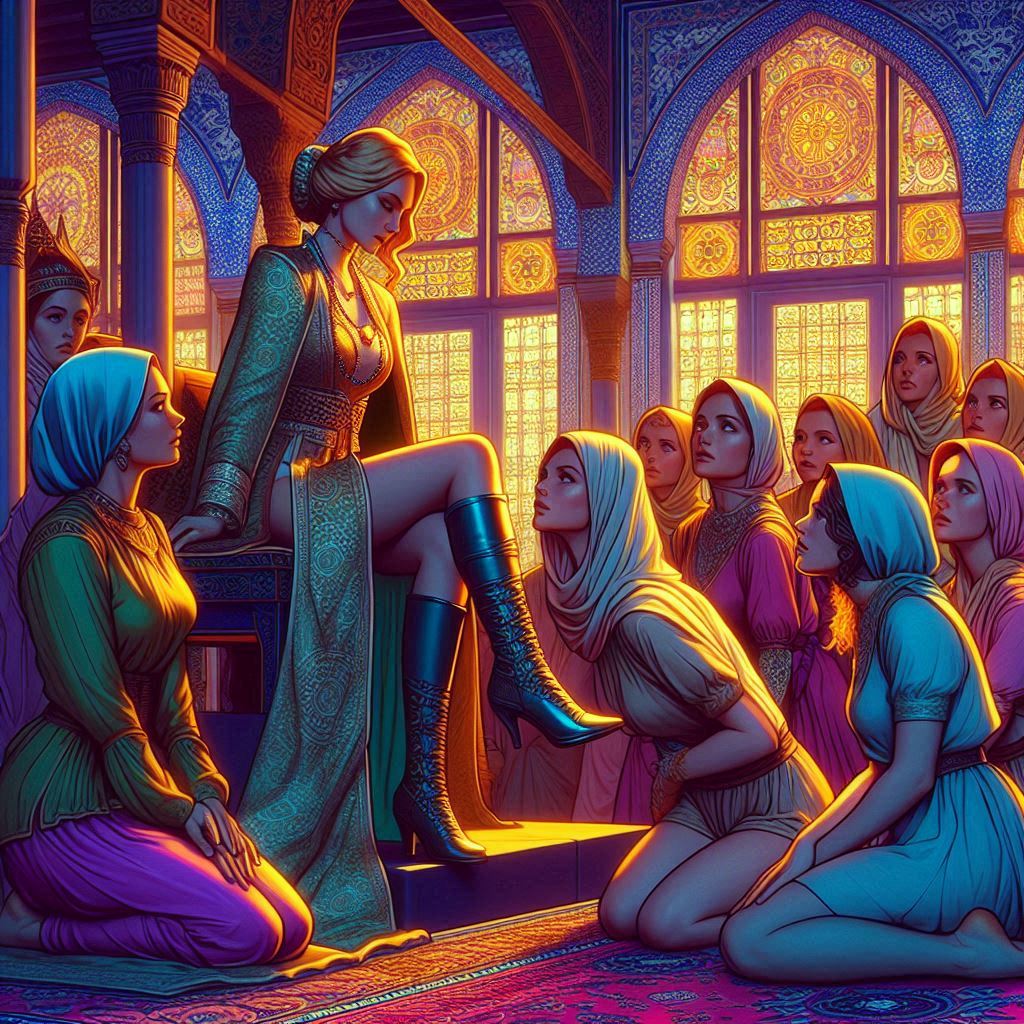

Within the windowless archive, with Chava’s guidance and encouragement, Pen found and raided the Venetians’ magic books, written in Latin, the language of religion and science in Western Europe, which Pen read and spoke fluently, along with his aristocratic caste’s language of Norman-influenced French, and his local language of English. He read all their titles for Chava, setting aside for Chava’s review the very, very few Chava didn’t already possess or hadn’t already known of, or that were so rare they would be difficult or impossible for the Venetians to replace. Although the books, collectively, contained many grains of truth, they also contained falsehoods and honest misapprehensions which the Succubae valued, not to keep their own magical primacy over humans, but to help them predict the actions of the humans who hunted them and the other creatures of hell.

Turning to the written records of the Council of Ten, even though they were written in Venetian (rather than Latin), a language Pen had only first been exposed to when his Aunt brought him to Venice earlier in the year, his Latin and French allowed him to read the spines, introductions, and section titles in the books well enough to locate what the succubae wanted most: The records of the interrogation, conviction, and execution of Anzola Ipato, by one Gasparo Orseolo of the Council of Ten, who had been burned at the stake on Wednesday, the 3rd of October, 1515. Morally, exposing an eight-year-old with even partial literacy of Venetian to such material was one of several testaments given during the course of the evening, to Chava’s limitations as a surrogate mother-figure. Technically, the very existence of the record was a testament to the efficacy of the Venetian secret service, which had accomplished something very few humans, human governments, or even human civilizations were ever able to achieve: identifying, capturing, and questioning an actual demon of hell: Tirtzah the succubus. After weeks of agonizing tortures, including especially vile and inhuman tortures methods devised by the Inquisition that were not normally performed by the Venetians (who relied heavily on the strappado), her mortal form, and thus her ability to visit Earth, was destroyed by fire, possibly the most agonizing form of banishment from the Earthly plane.

Chava had persuaded Pen to push, pull, and drag the heavy folio volume back across the church to her position in the Venetian Senate Hall. There, with Pen nestled on her lap, she read and carefully edited the record, using her magical powers and her great manual skills, to alter—as subtly as possible to try and evade any Venetians re-reading it from suspecting it had been changed—the text. As much as she estimated she could get away with, she replaced information learned about the succubae with inaccurate information that would be less helpful, or even self-defeating, the next time the Court of Lust tangled with the Serene Republic. Chava’s focus was on things Tirtzah had said that might hint at or reveal anything the succubae perceived as a potential weakness or exploit. Then she had made Pen reverse the difficult process of moving the volume back into the library. And because Pen lacked the strength to lift the folio-sized hardbound volume over his head back up to the high shelf he had pulled it from, she had him pull down all the nearby volumes and pile them up with the altered volume somewhere in the middle.

Pen also found and recovered for Chava, Tirtzah’s magical ring, which the Venetians had taken from Tirtzah. Ultimately, they had not been able to make much out of it since capturing it. By recovering it, the succubae ensured they never would.

Finally, Chava had tried various ways to help Pen make sense of a section of books written—and even labeled on their spines—with lines and geometric combinations of lines that Chava suspected was a Venetian code. This, neither she, nor any of the succubae, had anticipated: volumes so secret, they were encoded when written and kept within their very fortress and capitol?

In the end, she decided against doing anything with them, at least not tonight. Even if the boy started with the last volume and worked his way backward, dragging every single volume out to her, it might take him hours to bring her the volumes covering 1515. If, indeed, she could even identify which ones those were. And then to repeat her work on the Venetian-language records, she would have to decipher the code well enough not only to make sense of the text, but to try and replace existing words with credible substitutes. The only other option would be to burn the lot; but in addition to being a terrible and unnecessary loss of knowledge—a possibility she loathed on principle—it would be pretty clear to the Venetians someone had been in their secret archive and was trying to destroy at least something the Venetians had learned and hidden there. Chava couldn’t even be sure what the coded—or cuneiform, for that matter—books were, let alone whether they actually recorded anything about Tirtzah, which seemed unlikely. If they did, keeping a copy in Latin would rather tend to defeat the purpose of keeping a copy in code. And because Anzola Ipato’s trial was only two years’ past, thus alerted to an effort to tamper with their institutional memory, they could and probably even would reconstruct much or all of it—accurately—from living memories, which would completely reverse Chava’s efforts to destroy the Venetians’ Latin record of their recently-acquired knowledge of succubae. Destroying a vast knowledge without helping the succubae, and thereby making it unlikely she would destroy the limited knowledge actually harmful to the succubae? That would be the worst of both worlds, and she decided against it.

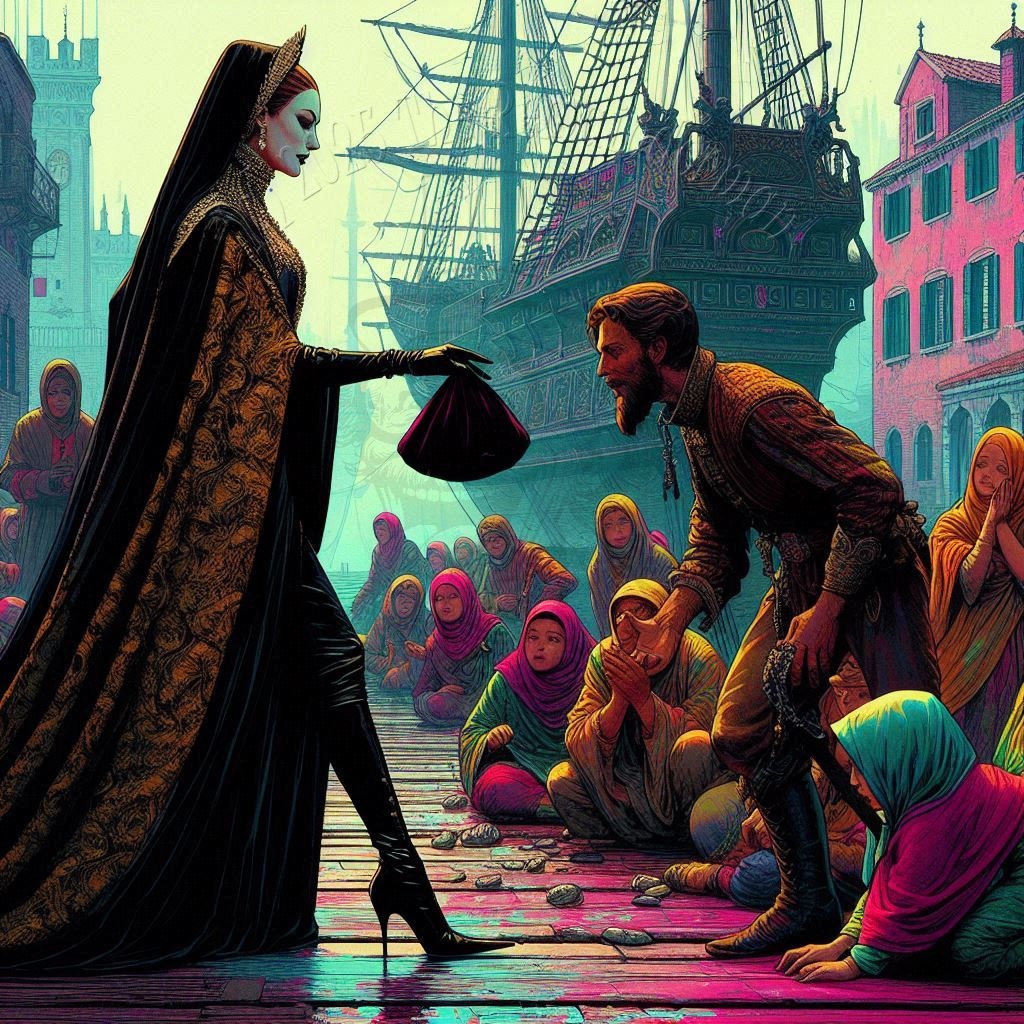

In the end, Chava—with Pen’s semi-witting help—completed her mission before Channah and Rivqah finished theirs. Instead of risking Pen coming out from under her influence while he was in the secret archive, and thus beyond her physical control, she brought him back to her and, inspired, decided to make the most of the opportunity by influencing Penny to do whatever he could, to save himself. Chava warned him he literally could not escape the succubae until dawn, and must avoid crossing Channah, or if possible even attracting her attention again, in the meantime. But once he saw any part of the sun, he should immediately, or as soon thereafter as possible, slip away when neither Channah, nor Rivqah, nor Miryam was watching him, and run for his very life. When Pen protested that Chava should come with him, or that he wanted to see her again, she promised that if he obeyed her like a good boy, she would visit him again in a week. Finally, still concerned that she had not impressed the danger upon him sufficiently, or persuaded him that a 5,000-year-old succubus didn’t need an eight-year-old boy to protect her, and having already used him to cross the sanctified church and plunder the secret archive, she added the force of compulsion to ensure his commitment.

Literature Section “06-124 Grimm Transformations VIII: Child Laborer or Child Soldier?”—more material available at TheRemainderman.com—Part 124 of Chapter Six, “Le Saccage de la Sale Bête Rouge” (“Rampage of the Dirty Red Beast”)—1264 words—Accompanying Images: 1960-1963—Published 2025-06-24—©2025 The Remainderman. This is a work of fiction, not a book of suggestions. It’s filled with fantasies, idiots, and criminals. Don’t believe them or imitate them.