3839 08-02 Entering Heaven in Dublin–St. Patrick’s Cathedral

PREVIOUSLY: Two traumatized boys of 5 or 6 residing on the militarized Southern border of the Pale have just been given into the care of the Augustinians: Char, youngest son of Lord Wrathdown, a finicky mommy’s boy and a bit of an airhead, has been banished to the Church to make a man of him; accompanied by a new ward of his father’s, the refugee of an Irish raid, who was meant to help him learn, but is still in a state of shock from whatever he has experienced there. NOW:

“I don’t think I’ve ever been so far from home before!” Char broke his silence in wonder all of ten minutes and a third-mile from Shanganagh Castle; and once he did, the dam was well and truly broken. The thoughts seemed to go racing straight from his brain to his mouth in a continuous flow like the water of the Liffey River.

“Really?” Friar Hugh asked in surprise. “Probably for the best, in an area as wild as this.”

“Lady Parnell doesn’t like any of us to wander far,” Char nodded, explaining: “There’s Irish savages everywhere.” And then added proudly: “I’ve seen them. One of them even talked to me!” he admitted in a scandalized voice.

“Why?”

“He was on the road and asked what the castle was named. I’m not supposed to speak to them, but he seemed human enough. Except I could hardly understand him. Even his English sounded Irish.”

“Did you tell him?”

“Yes,” Char admitted. “I didn’t want to be impolite.”

Friar Hugh, covering his amusement, asked: “And were there any ill effects? Of speaking to an Irishman?”

“There were. Lady Parnell was furious and smacked me on the mouth as a reminder not to use it with Irish.”

“Right,” Friar Hugh answered wryly. “Cause and effect it is.”

Rubbing his jaw as if to evaluate the spot, the child said: “I miss my mother. Ladies Parnell and Kynborow don’t like me,” he observed matter-of-factly. “But they aren’t nearly as bad as my wicked father.”

On a typical day, Friar Hugh might cuff a child for speaking ill of his parents; but he was trying to be mindful the boy’s whole life was changing unexpectedly today. The vulnerable, emotional quaver that frequently modulated Char’s voice helped to remind Friar Hugh of that. And, of course, in the case of Char’s father, it wasn’t disrespect so much as a simple statement of fact. The Wrathdowns and their ilk were among the most-notorious families in the Pale, and Lord Wrathdown was worst of the lot. Except, perhaps, the Shambler of Hell—although he was not a Wrathdown per se, he was one of the ilk and a terror in his own right.

By the time they were a half-mile from Shanganagh Castle, Char’s voice sounded like a cross between amazement and boredom: “Are we still in Wrathdown?”

In truth, Friar Hugh never felt as confident as he would have liked, about his location traveling between Dublin and Shanganagh. It wasn’t like there were signs providing decorations, or even clearly demarcated roads. Wandering astray would always be a concern here, so close to the Irish areas. But at least they were headed North to Dublin; it wasn’t like the trip South, where getting off the road entailed a real risk of getting so lost one could cross the pale in an unfortified area without even realizing they’d left English territory. “Aye, until we pass Castle Dundrum and a bit.”

“It’s so big! I knew there were nine castles, but we haven’t even seen another one yet!”

Friar Hugh laughed out loud at that. “Not so very big. Carrickmines and Dundrum are the only two you will see today, on the road to Dublin from Shanganagh. After Dundrum, we’ll leave the Pale behind us.” Char, and presumably the other boy, understood Friar Hugh was referring now to the earthen battlement and ditch itself, that stretched between the frontier forts around the English territory and gave it its name, rather than the region within it. “Dublin’s in the middle, of course. Your young friend came from around Keen Bray Castle, at the very Southernmost tip of Dublin County, and of the Pale. Probably, I don’t know…” Friar Hugh mused “Another five miles South of here?”

“Five miles?!” Char exclaimed. Then asked: “Is that far?”

“Not so very. But it means he’s walked further than you, so no complaining.”

“What’s his name?” Char asked suddenly, frowning at the other boy with curiosity.

“Pendragon… Pendragon…” Friar Hugh consulted the paper from the boy’s chest. “Pendragon Argent.”

“Pendragon,” Char repeated carefully, evaluating the boy and asking “You’re named Pendragon?”

The boy said nothing.

“He should answer me when I speak. I’m his superior!”

“He’s had an even worse day than you,” Friar Hugh pointed out. “Perhaps show him the same kindness I’m showing you.”

The little blond boy seemed to accept that, and nodded. “I will. Unless he doesn’t speak at all? Is he dumb?”

“The note doesn’t say anything about it, so I’d think not.”

At Carrickmines, and then Dundrum, the soldiers and their families addressed Friar Hugh and Char both, their officers recognizing Char and addressing him as “Young Master Charles,” even as he referred to them as Master, in an odd reciprocal show of respect for aristocrats and adults. They stopped at Carrickmines Castle for sext, the noonday office, praying, reciting psalms, and chanting with the soldiers there. Pendragon knelt and bowed his head, but did not sing, chant, or pray with them.

Several times on the long journey from Shanganagh to Dublin, Char’s mind—and thus his speech—wandered back to how sore he was, and what a brute his father was. But to be fair, he never spoke worse of his father than others. What the boy didn’t seem to give much thought to were the Irish, which were never far from Friar Hugh’s mind on his long, but fortunately infrequent, travels between Dublin and Wrathdown. How he longed to return to Dublin full-time, instead of feeling like a prisoner of the Baron—or more accurately, he supposed, a prisoner of the Irish forced to endure the oppressive presence of the Baron—in Shanganagh Castle. If he could have run the ten miles or so, he would have seriously considered doing so. As it was, he started every time he heard an unexpected noise, and moved warily, his heart racing, when they passed or were passed by other travelers on the long, lonely stretches of road further from Dublin, expecting they might prove themselves a captain of the road… or worse, a clansman. And he was a mendicant! When he took his vows as an itinerant monk, he hadn’t anticipated actually having to do so quite so much mendicating in a war zone. But at least, he told himself, he was poor; and his robes announced as much to all and sundry. The Irish called themselves Christian; surely they would not attack a man of the cloth. Especially one without anything to steal! He wasn’t a high-and-mighty prelate living like the king in an ecclesiastical palace. And the boy’s inability to remain focused on any one idea seemed to serve them as well as Pendragon’s stupor in keeping the boys moving. As impatient as he was with the children’s pace and constant distractions, at least they weren’t complaining much (or in the daft boy’s case, at all); and it wasn’t until they stopped for None that Char first remarked on being glad to get off his feet.

Hugh was almost embarrassed to find himself walking with this—apparently—utterly unafraid or even unworried boy, when Hugh himself was so anxious. But, he reflected, the boy was a privileged fool; that was all. He was more ignorant than Brother Hugh, not more courageous.

In addition to the size of the world and the sins of his father—that small fraction of them he knew about either of those subjects, anyway—the child’s topics jumped between the countryside, the weather, the few farmers and travelers they passed, the possibility of lurking Irish brigands, the state of the road, and occasionally his companion, whose hand Char still held, tugging him along behind him. It was a curious grip, holding on almost as if his life depended on the connection, even as he kept tugging on the quiet march boy every time the latter seemed to slow down or stop. Friar Hugh couldn’t tell if the daft boy was getting distracted, or simply was so lost inside himself he’d just stop and remain rooted to the spot for disinterest without Char’s constant urging. For Char’s part, there seemed to be two main drivers of his behavior: he was at once the typical little bossy Lord’s son assuming everyone else would and should follow him, and the young outcast child, needful and hungry for reassurance, clinging to the redheaded boy as much as leading him. Whatever the case, Friar Hugh consoled himself, Char kept the boy moving, and in the right direction, which was a blessing for Friar Hugh.

“So many houses,” Char marveled, shortly after None. (Friar Hugh counted 3 or 4 in sight, but they’d passed several others in recent succession), as they approached the River Dodder near Milltown. “How can they all survive on such tiny farms?”

“Some of them work at the mill.”

“The mill—is that it?!” Char asked excitedly, as a mill along the River Dodder came into view ahead of them, on the opposite shore of the river. Then he burst out laughing: “That must be the biggest wheel in the world!”

“I doubt it,” Friar Hugh demurred, eying the wheel appraisingly. It was a breastshot wheel, perhaps 10 or 12 feet across, with wide blades catching water from a millpond behind a stone dam perhaps 5 or 6 feet high. The water poured onto the blades about halfway up the wheel, spinning it counterclockwise from their viewpoint. “Yes, it’s a flour mill,” he confirmed.

Char giggled nervously when he realized the road ended at the edge of the water and resumed on the other side, excited and worried at the same time. They had already forded several streams on their way from Shanganagh, but nothing close to the Dodder. Char had never seen a rush of water like this one. “There’s no boat. Do we have to wait for a boat?”

“No. The water is shallow here. We’ll ford it.”

“We’re going to walk through a river?!”

“We are,” Friar Hugh grinned. “Now you shouldn’t cross a river when you don’t know what you’re doing, because they can be treacherous. So don’t take this too lightly. But I travel between Dublin and Wrathdown several times a year. Unless it’s been raining—which it hasn’t, particularly—the river is quite low here, and shallow, with good footing. I think you’d be fine on your own, but since the water moves a bit fast, we’ll hold hands just in case.”

“How high will it be?”

“Maybe up to your hips at the very middle?”

“I’ve never been in a river before!”

“After today, you won’t be able to say that again.”

As they approached the shore, Char’s breathing got heavier with nervousness, even as he felt his companion start to slow and resist more. Char stopped, turned to face the boy so the boy could not help but seem him despite his refusal to make eye contact, and holding both his arms, stressed seriously: “Pendragon? Pendragon!” He seemed satisfied when Pendragon finally flickered his focus across Char’s eyes for a moment. “We’re going to walk through the river! Do you understand? Come on! And stay to the left of us!” Once he understood their intention, he came willingly enough, surprising Friar Hugh, even stepping into the water before either of his companions.

“Are you sure it’s safe?” Char asked anxiously.

“Safe enough,” Friar Hugh responded, somewhat reassuring if not quite what Char was hoping to hear. Turning his attention to the other boy, he warned: “Hang on tight there lad, don’t get ahead of us! Hold tightly to young Master Charles.” Once they entered the water, Pendragon seemed much more solid-footed and confident than Char, which seemed to concern Char a bit at first.

“Have you done this before?!” Char demanded, an almost accusatory tone in his voice.

But of course, the dumb boy said nothing, except holding fast when Char, distracted, lost his footing and fell, prevented from being swept down in the current only by his two companions.

The day’s highlights, however, were still to come, hard to rank because they were each so different. But Char’s reaction seemed to be most pronounced at the first of these marvels.

After the river, farms and even villages became more frequent; and Dublin itself began to creep up on them, its urbanized liberties sprawling to the South of the City proper. It all hit Char, and possibly Pen, at once as they came over the crest of a small hill. Pen stopped in his tracks, and when Char glanced up, he gasped: “Holy Mother—excuse me, father! That—that—”

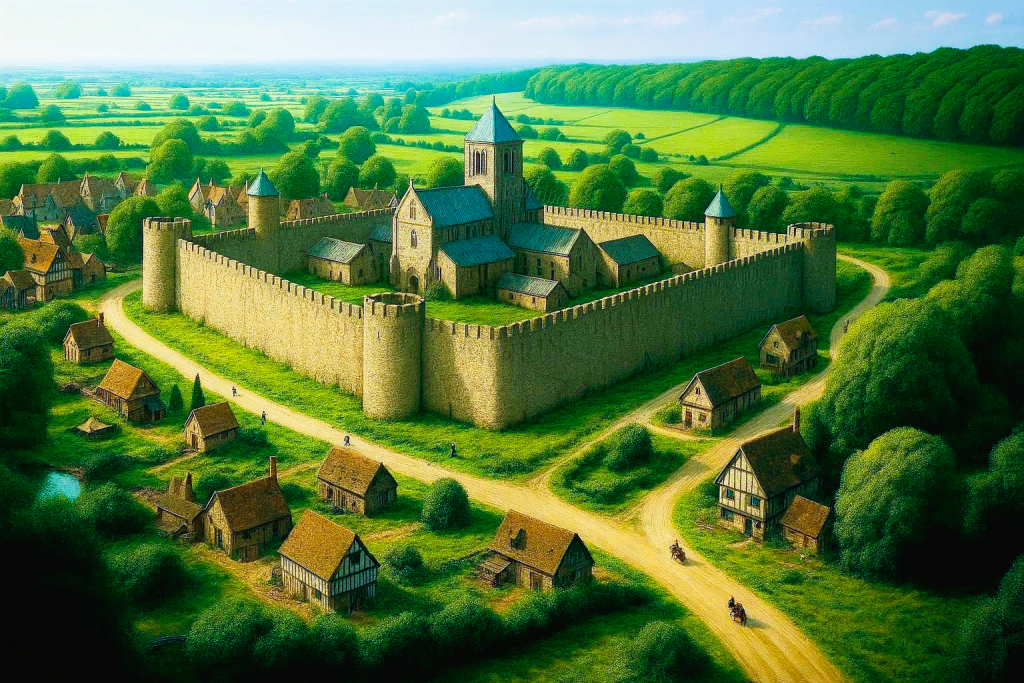

Friar Hugh laughed. “That is St. Patrick’s Cathedral, the largest church in Ireland!” A great stone church soared into the sky before them, comprised of two arched arms forming a cross, surrounded by an impossible number of homes, shops, and larger buildings clustered tightly around a network of narrow streets filled with people and wagons bustling about in every direction. The vast majority of the buildings were wooden, with a very few stone structures scattered among them. And looming behind them all, the massive stone walls of Dublin City stretched across the horizon.

“Is that where we’re going?” Char breathed in amazement.

“No, we’re going to the oldest cathedral in Ireland, Holy Trinity. Often called Christ Church. It’s our church.”

“Ireland’s?”

“Ireland’s, yes, but I meant, our Augustinian brethren’s, attached to our friary.” And with obvious pride, he told them: “Dublin is the only city in Ireland—maybe in Christendom, probably except Rome, of course, with two Cathedrals.”

“What makes a church into a Cathedral?”

“Trust your eyes, young master: It’s as near to heaven as any place on earth. Formally, it’s a church with a cathedra. And before you ask, the cathedra is the throne from which a Bishop rules his principality.”

“Does that mean there are two Bishops of Dublin?”

“No, a single Archbishop of Dublin with a single palace at Holy Trinity. But he has two cathedrals.”

“What does he need two cathedrals for?”

Friar Hugh’s face fell a bit, into a puzzled expression. “I… don’t know. Nothing, I suppose. They used to have a big to-do about it but they held a synod to reach a truce between the two cathedrals. So now they share the Archbishop.” Then he shrugged, nodding with renewed reassurance: “But the point is, Dublin has two cathedrals, and ours is the real one.”

“It must be truly amazing,” Char speculated, “To be chosen over this one—auckgh! I smell animals and shit and—and—I don’t know wha—!”

This time, Friar Hugh, deciding he was being too liberal and knowing a potty mouth on the boy would not serve either of them well once they reached the Friary no matter how horrible the language he must be used to hearing, did cuff him this time, cutting off his sentence and chiding him: “Time for you to remember you’re a church man, now! The days of cursing and imitating the vulgar ways of farmers and animals are over! The sooner you master that lesson, the better off you’ll be. And for your information, that, unfortunately, is the smell of Dublin. It’s not usually quite that bad, but you’ll get used to it.”

They were soon passing in the shadow of St. Patrick’s, and then that of the city walls as they entered through the massive St. Nicholas’s Gate. On a normal day, had the Cathedral not already jaded them, Char surely would have exclaimed with excitement to see, and then pass through, the gate. But he did proclaim his relief that they didn’t have to ford across this river, which Friar Hugh identified as the River Poddle. And Char did not try to keep moving when Pen came to a dead stop inside the tunnel, looking straight up above him at the grate and the murder holes. Instead, Char seemed fine with it, laughing at the sight of a boy lucky enough to be up in the fortress above them, perhaps the son of some officer, who was mimicking firing an arrow down on them. Char gamely fired back while Pendragon marveled at the massive stone around them, until Friar Hugh took Char’s hand, the same way Char already had Pen’s, and tugged both boys forward.

“You two, stay very close to me from now on, do you hear?” Hugh warned them, putting himself between the two boys so he could hold their hands. “It’s obvious you’re newcomers to Dublin.”

“Yes, Friar Hugh,” Char answered for both of them. “Why is that important?”

But there was no need for him to answer. The next moment, the first of Dublin’s beggars and street sellers began assailing them. Especially Char, who deduced it must be because his clothing was so much finer than that of his companions. But also, he thought, feeling just a little bit pleased, it just might be because he looked the most beautiful. That thought, in turn, darkened and troubled his mood, reminding him of the injustice his father had done to him today, how badly his back and bottom and thighs hurt (as if he needed more reminders of that), and most of all, of the massive and devastating consequence: that he had been banished from his very home! And while that suffering was his dominant reaction today, being recognized as beautiful (Char would not have said or thought that he looked like a girl, exactly—that was his beastly father’s insult), was always gratifying. It always had been, as long as he could remember. And now, although he wasn’t really aware of the fact, there was slowly emerging a in him a sense of defiance and even strength in who he was and his distinctness; especially that validation provided by the fact that he was beautiful and appealing to others, despite the awful untrue words of his father.

The rest of their walk was a blur to Char, so overwhelmed by new sights and smells and sounds and pitches from street people he could hardly keep up with them all. Even if Char had been inclined to loiter and observe anything more, Friar Hugh wouldn’t have let him. Fretting about the imminence of the ninth hour of the day, he urged them to walk faster despite the distance they had already come since morning.

When they finally arrived at the Friary, Char’s main feeling was one of relief: relief that their long walk was over and he could rest his feet and legs; relief that Friar Hugh would not be taking Char any further away from the only home he had ever known (although he wished fervently, he was not as far away as he was); relief from the constant sensory overload of the unfamiliar city streets around them; and relief that the Friary seemed, well, nice. Or at least, as nice as anyplace other than Shanganagh Castle could ever be. Char was quite relieved Friar Hugh didn’t ask him what he thought about how the Cathedral compared with St. Patrick’s. Char knew he ought to answer Christ Church was better; and he wanted to. He was loyal! But the truth was, he didn’t even know how to compare them to each other. They were the two largest churches he had ever seen, and while he could tell the architecture, outer buildings and even, to some extent, the layout of the buildings were different, they were really, compared to everything else he had seen in his young life, similarly remarkable. They were more like one another, and distinct from everything else. Probably, he would come to appreciate how Christ Church was better than St. Patrick’s as he learned more about his new home.

Char was astonished when Friar Hugh led them around the cathedral and back into yet another one of the teeming streets of Dublin to reveal yet another church, right across the street from Christ Church! Compared to the two cathedrals, he supposed this latest church could be considered a regular church, even a small church; but it was easily the size of Shanganagh castle itself. And Char was pretty sure he had seen more churches to his left and right in the short time it took them to get from St. Patrick’s to Christ Church. Char thought there were more people on each block and lane they saw, than he had encountered in his entire life living at Shanganagh Castle; but even so, he couldn’t imagine what they needed so many churches for. Not when Christ Church and St. Patrick’s were so huge! He was sure the entire English population of Ireland would be fit into either one of them without feeling crowded. Finally, beside the second church, across the street from Christ Church, they reached a cluster of suitably sober wooden and stone buildings a couple of blocks Northeast of Christ Church Cathedral itself.

Just as they approached the entrance, they heard a peaceful, joyful, musical sound coming from high above Christ Church Cathedral. Char whirled and looked up for their source, asking: “Are those bells?!” Even Pen instinctively looked up for the source and gasped.

“They are. They’re announcing the hour.” The boys certainly understood he meant the canonical hours. They were practically the only hours that counted, for most people. Friar Hugh led them onto the Friary grounds, finally letting go of their hands as they entered another small church (which Friar Hugh explained was a private one for the friars), then turned through a door in the side of the nave that led to the back of the refectory, where a man Char would soon learn was the Archbishop of Dublin himself, was calling the brothers to Vespers, the sunset prayers. Catching sight of them, he frowned curiously at Friar Hugh, who Char thought reacted almost as if he were nervous, before returning his focus to the office. This one was much longer than None had been, or indeed any service Char had ever been to except the mass, consisting of an opening responsory; the singing of hymns, psalms, and canticles; a reading from the Bible; another responsory; the Magnificat, including the canticle of the Blessed Virgin Mary, accompanying antiphons, and Gloria; the spreading of incense; the intercessory prayers, the Lord’s Prayer, the collect, and the blessing; followed finally by the Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament.

Again, Pendragon made the appropriate physical motions, matching those of everyone around him; but did not sing, chant, or pray, and neither seemed to pay attention to, or disregard, the Archbishop when he spoke. Char couldn’t believe how long the office continued. Even back at the castle, it was all he could do not to fidget and get in trouble.

When adults caught Char, or one of the other problem children, rolling their eyes during the service or complaining about it afterward, he would stress how the interminable singing and chanting and reading of Bible verses they had heard a thousand times before and frequently several times earlier in the same day was supposed to make them feel reflective and contemplative. When Char had laughed, quite spontaneously and unintentionally, at the idea, his father—the most impious person Char had ever encountered—walloped him, and he learned to act contritely no matter what he was feeling inside. Well, mostly. Now that he had joined—or, more properly, been joined to—the religious life, he was about to encounter a daily divine office, six times a day and once in the middle of the night, he could never have imagined before. Poor little Char. Even with this first tiny taste of the many spiritual challenges the religious life would confront him with, he had no idea.

After it was over, Friar Hugh waited nervously, greeting those of his senior brothers who made eye contact with him as they left the refectory. Most of them had spent the time between None, announcing the end of the workday, and Vespers, in the cloister or the calefactory beyond. Now they went to ready themselves for bed. Their curious glances, and the intimidating glare of the archbishop, made it clear how unusual their presence here was. It also struck Char what a contrast the two of them made, Char clean and fine in his embroidered dress and expensive shoes, while Pendragon was rough and barefoot in his simple dirty and blood-spattered robe.

With a sharp sigh of resignation, Friar Hugh motioned them forward and Char took Pen’s hand to pull him after them: “Come on, stupid.” The archbishop had signaled two other, older brothers to wait with him, whose robes marked them as holding rank within the Augustinian Order; but having never been to a religious community of any kind before, Char could not identify their offices from their appearance as readily as he could identify the Archbishop.

Friar Hugh bowed his knee to the archbishop, imitated closely by Char, greeting him as “Good evening, Lord Dublin. Provincial Clement. Prior Stephen.”

“Good evening, son,” the archbishop responded on behalf of all three men, his frown sharpening at Pendragon, who seemed to notice his companions kneeling but was slow to imitate them, something like confusion touching his otherwise still-daft features. “Now who are these children, why have you brought them here, and what is wrong with that one?”

“This is young Master Charles, My Lord, the son of Lord Wrathdown.”

“‘Pon my Faith,” the Archbishop interjected without even thinking, at the mention of one of the Friary’s biggest sponsors, shaking his head. “Another one?”

“I apologize, My Lord,” Friar Hugh clarified. “I was unclear. This is his youngest child by his marriage to the late Lady Wrathdown.”

“A legitimate son? That’s going to be a different problem altogether, isn’t it?” the archbishop looked askance at his colleagues, who nodded ruefully.

Char didn’t understand what they were talking about, or what could possibly be unclear about describing him as his father’s son.

Looking back at Friar Hugh the archbishop demanded: “And you agreed?! And to this… who or what is this?” he gestured towards Pendragon.

“Lord Wrathdown is… I’m afraid, most persuasive, my Lord.”

“Horrifying, you mean!”

“But perhaps we should discuss this privately?” Friar Hugh suggested, looking askance towards Char.

“Can Prior Stephen deal with this?”

Friar Hugh looked pained. “Ah… Lord Wrathdown suggested they might join the cathedral chorus…?”

“God’s fury! Choirmaster Adam—” And with a glance toward Char—whether from concern for a child’s welfare, or concern about what said child might reveal to Lord Wrathdown, was unclear, “Yes. Of course. Come along to my office.”

The boys followed the men out from the rear door of the refectory into the cloister, where several monks wearing heavy leather gloves were paired against one another, hitting inflated bladders back and forth between them, sometimes even bouncing them off the walls, while other friars watched or spoke with one another. Char, and even Pendragon stared in amazement at the spectacle, both of them stumbling over the same crack in the cloister walkway as they stared backwards instead of watching where they were going.

At the sight of the Archbishop, men shifted nervously or looked away. Before Vespers, the cloister had been much more crowded. Playing after Vespers was not strictly prohibited, but his gaze reminded them they had better things to do to prepare themselves for sleep so they could rise refreshed at 3 in the morning for Matins. Had the Archbishop remained in the cloister, or the adjacent calefactory, doubtless the monks would have quickly found better and higher purposes for themselves.

After a quick walk down one side of the small cloister, they stood in a corner with an open door to a library on their left, and an open door to a short entryway in front of them, with the calefactory on the other side of it and a steep stone stairway to the left of it. The archbishop led his friars up the stairs and out of sight while Friar Hugh herded the boys against the wall of the cloister into the small corner between the two doors. “You two, wait right here and watch the game,” he instructed them, nodding for emphasis, before turning and hurrying after the archbishop.

Char, his ears burning to know what they were saying about him and his family and why they didn’t want him to hear, immediately looked at Pendragon and urged him: “Come on, let’s go!” He began walking and pulling Pendragon’s hand, but when the red-headed boy followed him too slowly, he hissed: “We can’t wait! Keep up!” over his shoulder. Frustrated with Pendragon’s lack of speed, he let go of Pendragon’s hand, and hurried up the stairs before any of the monks sitting in groups chatting animatedly around the fireplace in the middle of the calefactory, took any notice of him.

The stairs wound tightly in a “U” shape, to a hallway above the calefactory leading to a muniment room (a vault for protection of the brothers’ vital papers), other small dark rooms, and the Archbishop’s office, or episcopacy. Char was just in time to see the episcopacy door closing behind Brother Hugh. Motioning Pendragon to follow, Char scurried quietly to the door and pressed his ear against it.

It was only then, turning his head back the way he had come so he could push his ear flat against the door to listen, that he realized Pendragon was nowhere to be seen. Pressing his lips together to prevent himself from cursing aloud, he felt torn about whether he should go find him. But the chance of the boy going anywhere without Char pulling him seemed small, and he was simply too curious to abandon his post.

The archbishop was speaking: “He’s never shown any interest in song or—” the archbishop snorted as the other men in the room laughed. “Any aspect of Christianity or civilization, for that matter, before. Except weaponry. Is it his new wife? Does she have an interest in the church?”

“No… Lord Wrathdown is concerned the ladies of the castle are exercising an undue influence on him, and wants us to make a man of him.”

“Then why doesn’t he squire him out like his brothers to one of the other marcher lords?”

“The lad does have more of a… religious disposition,” Friar Hugh explained. “Patient and social.”

“He didn’t even know what to do with the boy, did he?”

“But, unfortunately, ah—not a serious intellectual.” Charles felt himself blush red with a combination of humiliation, hurt, and anger, knowing it was true but still affronted to hear others saying it. It made it worse he couldn’t completely make sense of what they were saying. But he understood this.

“Ah,” the Archbishop pronounced, as if finding something wrong with a discounted apple. “Of course not. And the bastard—a simpleton?”

“I actually don’t think he’s Lord Wrathdown’s. According to this letter from Brother Matthew, the parish priest for Keen Bray, he’s Pendragon Argent. His father was Lord of the Manor in Raheen-a-Cluig. The whole family, and practically the whole manor, were slaughtered or enslaved by the O’Brians and the O’Tooles.”

The other men made sounds of sympathy and condemnation.

“He claims the lad is quite bright and intelligent, although he hasn’t spoken a word since seeing his family butchered. Lord Wrathdown wanted him to accompany his child into the church as a tutor to help him with his studies.”

“It seems that would be useful,” the Archbishop conceded, “If he’s actually diligent, and if he recovers from his stupor. Otherwise he’s just more dead weight. But in any event, he’s still another lamb from Wrathdown for us to tend. Are they particularly good singers?” he asked hopefully.

“I don’t know, My Lord. Lord Wrathdown didn’t say.”

“Didn’t imagine that was important for our chorus, did he? I mean,” laughing again, “He’s never shown any interest in song.”

“Or prayer,” Provincial Clement noted.

“Or, really, any part of the service,” Prior Stephen concluded as the three of them chortled.

“Brother Matthew’s letter pleads in the strongest possible terms for Lord Wrathdown to place the orphan in a school, the best to be found,” Friar Hugh explained. He didn’t need to add “which is us”—it would seem almost like a betrayal of the Augustine order to suggest otherwise. “He was more interested in his own boy’s education and vocation than singing, I think, My Lord,” Friar Hugh suggested.

“He wants that Manor for one of his older legitimate children, you mean,” the Archbishop retorted. “The daft lad is never going to be a knight no matter what his disposition. But if they can’t sing—you know how particular Friar Adam is about his angel choir! Every one of them must have the perfect voice and the perfect look. He’s threatened to quit before! I’ll never hear the end of it if I force him to start taking on bright-haired choristers just because they want to go to school!”

“Perhaps they could attend his grammar classes, but not the choral ones or sing in the choir?” the Provincial proposed.

“But they’re obviously still children! What do you think—at least another year or two until they’re ready for grammar school? The Augustinians don’t operate dame schools!”

“Or any facilities for the care of children, except—”

“The bastard house.” There was a shuffle of uneasy laughter.

“I’d prefer we refer to it by its proper name, please: The Augustinian Charity House of Our Ladies of Lesser Mercy Mary Magdalene and Salomé,” the Archbishop clarified, his tone managing to change from warning to thoughtfulness in the course of a single sentence.

“But… surely not for the Lord’s legal child?” Prior Stephen sounded worried.

“It’s been good enough for his bastards. Not a word of complaint in almost a decade now. Not from any of them.”

“Not a word of any interest at all,” the Prior conceded, “but for a child carrying his own name….”

“There doesn’t seem to be great warmth between them,” Friar Hugh conceded.

“Then why not just send them to Sister Phillipa?”

“That wolf’s den?” Provincial Clement asked skeptically. “I mean… Phillipa’s were one thing, and that made it logical to send the others, but… They’ll eat these two alive, won’t they?”

“It’s the only orphanage in Dublin!”

“But what other choice do we have?”

Sounding thoughtful, the Archbishop mused: “What if we put them in the Charity House, but we could find them a more-suitable guardian?”

“What lady of character would agree to live there?”

“She’d be living at the orphanage, not the… grange buildings. It’s a perfectly respectable street. What about the boy’s governess? Could the Baron be persuaded of the importance, for continuity and his acculturation…?”

“I’m not sure,” Friar Hugh prevaricated. “The Baron seemed… personally fond of her…”

The Archbishop, the Provincial, and the Prior all groaned loudly and incredulously.

“And she’s the boy’s step-aunt. But the Baron ordered all of his new wife’s family to leave Wrathdown as soon as his next child is born because he doesn’t want any weak female influences on his next son. So…”

“That’s ridiculous! Who else is going to raise children this young?! I’m going to consider how we might persuade her to join us at the Charity House, preferably without Lord Wrathdown learning about it quite yet….”

“Another one!” Char was confused for a moment trying to identify the voice, that of someone new, so intent on hearing the faint speech through the door he was ignoring the hallway altogether, before he caught movement from the corner of his eye and scrambled to something like a position of attention at the sight of an elderly man with a slightly hunched back moving with difficulty, but determination, dragging Pendragon behind him.

Char, caught and momentarily panicked, looked around as if there might be somewhere for him to run; or indeed, as if he had any reason to run. But having been found, any reaction was already too late. The old man was throwing open the door of the episcopate and hauling both boys inside by their arms.

“These must be the little scoundrels Brother Hugh brought us!” he roared, as the men in the room turned and looked at them in surprise.

The Archbishop’s office was unremarkable except for its relative warmth, a product of its location above the calefactory: The space itself was quite small, and although his personal effects were well-appointed, appropriate to his position as a member of the nobility, they were not excessive. It was more a case of the reasonable things anyone would keep in their office, being of the finest quality; than an ostentatious display of wealth showcasing unnecessary possessions. It was entirely in line with Char’s own experience and expectations; if anything, it was the simplicity and basic functionality of the Friary’s other furnishings that stood out to Char. It would have been too strong to say this room was the first place he felt at home, even with a rough manor like that of Castle Shanganagh for home; but it was familiar to him. There were only two chairs besides the Archbishop’s own, occupied by the Provincial and Prior, with Friar Hugh standing attentively to one side of his three superiors.

“I found this one listening outside the door, My Lord!” the old man growled as Char turned scarlet with embarrassment. “And this one tearing up the books in the library!”

“I would never damage a book!” Pendragon exclaimed, surprising them all not only by speaking, but with his vehemence in defense of books, which turned immediately to a gushing tone of praise: “You have so many, I just had to investigate! Father Matthew told me about the libraries in Dublin but you have three whole rooms of books! And the moment I saw your Pentateuch I knew at once it was an illuminated manuscript!”

The room froze for a moment. The four churchmen determining the boys’ fate looked nonplussed as they tried to catch up with the rapid sequence of interruption, charge, and information bombarding them. Char, who hadn’t really believed Pendragon could talk at all, stared at him in shock for that fact alone, without registering anything about the content of his speech. But the old man seemed to be the most surprised of all, well and truly flabbergasted at the words coming out of the boy’s mouth.

“What?” He asked, automatically, without even thinking about it.

“They’re even more beautiful than Father Matthew said! I want to make illuminated manuscripts.”

The churchmen looked at one another suspiciously for a moment, as if trying to sort out how they were being tricked.

“You can’t read!” the old man charged impulsively.

“He’s of gentle birth, Brother Griffin,” Friar Hugh explained. “Despite his appearance. He’s just barely survived an Irish raid that destroyed—well, a bad Irish raid,” he amended hastily, not wanting to re-traumatize the boy. “Can you read Latin?” he asked the boy, feeling compelled to prompt him as if, by being forced to bring him to Dublin, he had become the boys’ involuntary sponsor and patron.

“Latin and English well, Father. A little bit of French and Irish too.”

“Iri—!” several voices began at once.

But fortunately for him, he immediately diverted their attention by concluding: “But I want to learn Greek, most of all!”

“You what?!” The Archbishop asked incredulously.

“Greek?” Char blurted out, confused and still off-balance from being caught. “What’s that?” And then, without meaning to or understanding he had done so, he asked what everyone in the room was thinking, but none of the clergymen wanted to ask because questioning the desire to learn was so at odds with their educational mission and role: “Why?”

“Father Matthew says that by reading works in Greek, Erasmus—”

“Erasmus!” several voices cried in surprise.

“—is discovering an entire lost world of knowledge and faith! More important than the Spanish Conquistadors in the New World.”

Pendragon stopped, realizing everyone was staring at him slack-jawed and misinterpreting the silence. Nervously, he added: “I’m sorry for speaking out of turn, Masters.”

A cunning smile slowly spread across the Archbishop’s face, beginning in his eyes before reaching his mouth. His Augustinian brothers, familiar with this look, suddenly glanced at one another nervously. “You’re sincere in this, aren’t you, child?”

“Oh, yes My Lord!”

“I only know of one speaker of ancient Greek in all of Ireland,” the Archbishop spoke slowly, looking at Father Griffin. “And he’s most eager for students.” It would have been more accurate to say, he was vociferous in his praise for the ancient Greeks, their philosophy, and their language; and seemed unable to contain himself from urging his brothers to take up the language and suggesting the ability to read Greek was a virtue in the church.

“I would be honored to meet him, My Lord.”

“You already have. He’s standing right in this room.” Pendragon looked astonished.

Father Griffin’s face, cycling rapidly between expressions, betrayed the fact he might have objected in other circumstances; but he was clever enough to recognize when he had managed to entrap himself, and sensible enough not to argue from a position of weakness with the Archbishop once he’d made up his mind. He grasped at the only means of escape available to him:

“But—My Lord, they’re children! Not even ready for grammar school. Not yet of an age where they can even comprehend reason.”

“Brother Griffin is right, of course. You both are too young. As they have both demonstrated tonight by ignoring Friar Hugh’s instructions. But as I reflect upon our conundrum, your father” he addressed Char “and your mesne lord, now that you’re the head of your family,” he looked meaningfully at Pendragon, “Has made it clear his will is to place you in our care, whether any of us think you’re ready for it or not. So, you have exactly two choices,” the clever Archbishop, an expert manipulator of people, concluded. “You” (looking at Pendragon) “can, against all odds, have your heart’s desire, to learn Greek, as you claim you wish—if that is what you truly desire, if you only help your young master here to behave himself and learn well enough to remain with us. And you” (looking at Char) “Can learn what Greek is, and at least do your best to act like you’re suited to being a man of the church, while you try to become one with the help of your young friend.” Turning to Father Griffin, he continued: “You can show your brothers the value and inspirational meaning of Greek, andI can let Brother Hugh report back to Lord Wrathdown that his wisdom is indisputable and his donations to the Augustinians are as useful to him in this world, as they will be in the next.”

“Or.” He paused, looking around at all of them to ensure they understood the gravity of the next part, landing on Charles first. “We can send you back to your father, telling him you’re too undisciplined for the church, ignoring your superiors and listening at doorways!” Char shrank back, swallowing and shaking his head at the suggestion, even before he finished the thought: “You’ll have to squire for him and your older brothers if no one else will have you.” Prior Stephen looked pained at the degree of stress the archbishop was putting on the poor boy. The Augustinians all knew returning him to his father would be an extreme last resort because it would incur his displeasure. But Char didn’t; or at least, he was much more sensitive to the ire that would be directed at him, than at these churchmen. Turning to Pen, the archbishop continued: “And we can send you back to Brother Matthew, telling him he overestimated your interest and aptitude.” Finally turning to Brother Griffin: “And you can give up on this rare opportunity to share your gifts with someone who is genuinely interested in them.”

“I understand, my Lord,” Brother Griffin answered, seeming more chastened than upset. “Your wisdom is indisputable. But truly, I’m afraid I know little about teaching and caring for children.”

“None of us” and here he may have been referring to the religious brothers of St. Augustine in Dublin, or more broadly to the entire male gender, “do. Or even about the teaching and care of young men, except Brother Adam. These two will have to live for now with the other children in our care, at Our Ladies’, until they are old enough, and their voices ready enough, that we can induce Brother Adam to accept them. See if a singing teacher can be arranged for them and let Sister Phillipa know they should have a separate room from the others. With a window, in case Lord Wrathdown should inquire. And attention and care appropriate to a noble child. In the meantime, the boys will attend the Dame School in the morning and study Greek with you, Brother Griffin, in the afternoon. When they can convince you of their ability to study and behave, they will commence studying Latin, French, and English with the other choir boys in the morning; and when they can convince Brother Adam they’re ready, they can try out for his choir.

“In the meantime, they will observe the full holy offices when they are in our care, just as the choir boys do; but when they are with our lay brethren, they may continue the more relaxed observances at Our Ladies’. Since the chorus, the library, and the orphanage are all properly affiliated with Holy Trinity Friary, I’m certain Father Stephen can coordinate the details of their care and schedule as he sees fit without being troubled by Provincial Clement or me.”

Provincial Clement looked as pleased with the arrangement as Archbishop Dublin was with himself for solving several problems at once whilst extricating himself from all of them, spoiled only when he saw the look of confusion and worry on Pendragon’s face. “What?” he asked, not quite with the solicitous tone of voice a young man under the Cardinal’s care might want to hear. But the prelate couldn’t have imagined what was coming next.

“My Lord, it’s just—” Pendragon swallowed nervously, looking around the room, looking embarrassed, before whispering: “Holy Trinity Friary is in Dublin!”

“Aye?”

“How did I get to Dublin?!”

Literature Section “08-02 Between Heaven and Dublin, England”—more material available at TheRemainderman.com—Part 2 of Chapter Eight, “The Wild, Wild West”—6657 words—Accompanying Images: 3839-3842—Published 2025-12-27—©2025 The Remainderman. This is a work of fiction, not a book of suggestions. It’s filled with fantasies, stupid choices, evil, harm, danger, death, mythical creatures, idiots, and criminals. Don’t try, believe, or imitate them or any of it.