4553 08-03 Charite Hous exterior

CAUTION: Contains themes of fighting, bullying, and abusive behavior towards children some readers may find disturbing.

If this account is closed, look for “Remainderman” or go to theremainderman.com

PREVIOUSLY: Two traumatized boys of 5 or 6 residing on the militarized Southern border of the Pale have just been given into the care of the Augustinians: Char, youngest son of Lord Wrathdown, a gentle nontraditional boy and a bit of an airhead, has been banished to the Church to make a man of him; accompanied by a new ward of his father’s, Pen, the refugee of an Irish raid, who was meant to help him learn, but is still in a state of shock from whatever he has experienced there. Accompanied by Char’s tutor, Sindonie, and her son Oliver, they are being taken to their new home. NOW:

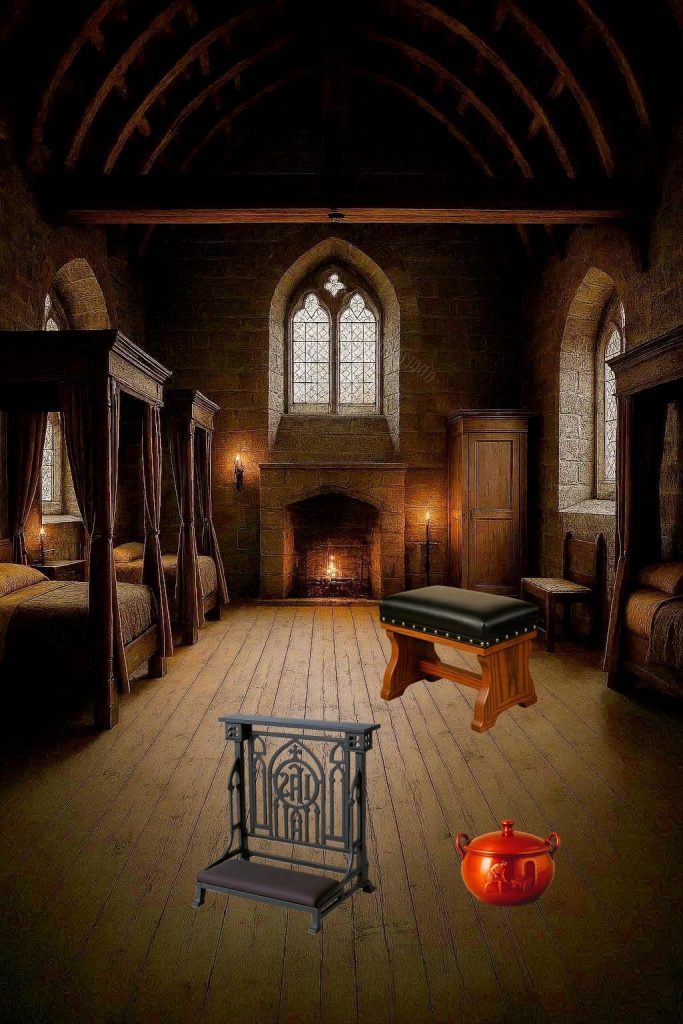

Just as Friar Paul knocked—well, pounded—the heavy wooden door of the Charity House again, they heard an eruption of children’s voices from inside. Movement from the windows on the right caught their eyes and they saw children’s excited faces pressed up against them, eager to see who could possibly be knocking on the orphanage door at such a late hour.

Vespers had come and gone on the road, shortly before they dropped the Archbishop off at his Palace outside the City; and it could fairly be judged Compline—bedtime—now. Brother Paul cringed visibly as he braced himself for Sister Phillipa’s reaction to the obvious disruption their late arrival had caused.

Arriving on Bothe Strete outside the Charite Hous, Brother Paul had hesitated with one foot out the door, forcing Sindonie to reverse her forward momentum to follow him, he cleared his throat: “Oh, and by the way, you can call Sister Phillipa, Mother Phillipa.”

Sindonie was taken aback: As in every sphere of life, titles and ranks were the prerogative of men, with a very few exceptions the nobility preserved to protect their own families’ special privileges. “Mother” was an honorific the Church was practically loathe to bestow on any woman; and was normally reserved for those few, rarified sisters named Abbess or Canoness the male bishops and cardinals could not seemly avoid appointing to run esteemed all-female institutions of the church.

Sindonie knew before they arrived, of course—had known the moment the orphanage was first mentioned—it could not possibly have been an esteemed institution. It was understood; orphans were little better than madmen or criminals; indeed, many if not most of the orphans had probably been found in the street and rounded up in the first place by the City Watch for breaking the vagrancy or other criminal laws, and offered to the Charite Hous because they seemed even younger than most. By extension, Charite Hous was little better than the Black Dog: Dublin’s notorious prison, housed like a parody of an inn in one of Dublin’s decaying defensive towers above a space rented to the slightly-less-notorious tavern that lent the prison its name. That was the City Watch’s next stop for anyone Mother Phillipa didn’t like the look of; a responsibility she wore heavily, as evidenced by a fair fraction of the children any other nun in the city would have turned away instead of fighting, valiantly, to save.

“Mother Phillipa—she’s the Abbess of St. Mary de Hogges?” Sindonie asked in shock.

Friar Paul laughed. “No, of course not. Just salt of the Earth. But everyone calls her ‘Mother.’”

“Even though she’s really a Sister?”

“It’s much simpler.” Char and Pen both giggled behind her at that suggestion. The fact they shared a sense of humor ought to help them bond; and she was inclined to laugh, too; but she settled for the skeptical look Father Paul caught on her face as he helped her from the carriage. “That does sound odd,” he admitted, allowing himself a smile. “But you’ll see. All the children call her ‘Mother’ anyway. And there’s another Sister Phillipa; this keeps them straight.”

“As long as the Abbess doesn’t mind…” Sindonie suggested tentatively.

“Not at all. Mother Phillipa isn’t known for putting on airs or getting above her station. Salt of the Earth!” he repeated, as he pounded on the door of the orphanage’s neat but generally—with the exception of several brass plaques announcing its function—modest and simple exterior.

Thus prepared, Sindonie was curious but not surprised when the door was opened by a fat, tired nun who looked entirely unhappy to see them. She was plainly as uninterested in facing and handling another unexpected situation today, as the small children behind her were thrilled by the break in their routine. Especially just before the wearying nightly ritual of going to bed. Sindonie could detect no airs at all floating around her; just practicality, exhaustion, and good intentions. She liked and pitied the woman immediately. The only thing about this woman that didn’t match Sindonie’s expectations was her apparent lack of resentment at her surroundings, her situation, her very life. It was Sindonie and her charges who didn’t belong here. (They soooo didn’t belong here…. But there was no benefit dwelling on that.)

Mother“What—” she began wearily and suspiciously. When her eyes fell on Sindonie and the three children clustered around her, her shoulders tightened and she started shaking her head. “Oh, no. You—” and then she saw Friar Paul and her entire countenance, from face to body, fell into something closer to simple exhaustion and disbelief. Her voice was flat: “Brother Paul.” The soldiers, barracked at Dublin Castle, had peeled away up Castle Strete when they turned down Bothe. But the carriage, its weary, sore driver, and its likely weary, sore horses, still stood behind them. At the sight of them, Mother Phillipa seemed to shake her head signaling it was too much for her to process. Fancy coaches didn’t come down Bothe Strete quite this far; they stopped at Pillori Place at the King & Lord, or occasionally at one of the other, relatively-moderate establishments buffering the successful merchants and nobles staying at the King & Lord, from the orphans at the Charite Hous, and the even less-savory forms of life further down the road.

“Bless you Mother Phillipa, it’s not as bad as it appears, I promise,” Paul began, sounding apologetic and pleading, a tone close to whining despite the weighty credentials he began by asserting: “Lord Dublin has been asked by Lord Wrathdown—” (she groaned) “but this is different, really!” he felt compelled to promise, before plunging on: “These three boys come with their own governess!”

That did get Mother Phillipa’s attention, and she looked back askance at Sindonie, running her eyes up and down her, giving her the same expert rapid-fire appraisal a hog-farmer might make of a pig at market, her eyes finally catching and sticking on the little blond child and his fine clothing. She might have gasped, just a little bit, she was so surprised. “No… surely…”

“Yes,” Friar Paul nodded and smiled encouragingly, confirming her most unlikely imagining. “This is Young Master Charles, youngest son of Lord Wrathdown’s name.” Something stirred among the children behind her, although none of the nocturnal arrivals could really tell what it was about; and wondered if perhaps they’d imagined it.

“And of course, the other two are…?” Mother Phillipa began, hesitant to say “bastards” or anything similar to it. She had actually taken on this mission, long ago, with the thought she could find satisfaction and help herself by helping orphaned children. She wasn’t a mother to them, at least not on purpose; but she didn’t actually dislike or resent the children, the way some of the nuns assigned to help her from St. Mary de Hogges did.

“This one belongs to me,” Sindonie smiled with genuinely motherly pride, letting go of Charles to bring her son in for a full hug close behind them, something defiant daring anyone to argue with her or minimize her child creeping into her expression and voice as she announced him: “Oliver Manning of Swords, rightful heir to his Manor, and Squire of Lord Skremen. He will be staying with us while his grandmother is attending my sister, Lady Wrathdown, who is with child. Lady Parnell will take her back to Skremen with her when she returns.” As intended, she had dropped more names and titles and estates in those three sentences than Mother Phillipa and all her wards combined could drop if they were given as much time as they needed to compose lists. As was inevitable, her circumstances—being sent to an orphanage to tutor for a noble child banished here—hinted at a great deal more back-story, only confirmed by her edge of defensiveness.

Nonetheless, Mother Phillipa, as practical and hard-nosed a woman as she was, curtsied. “Such an honor,” she offered, not quite what Sindonie, Oliver, and Char were technically owed; but more polite than anyone was likely to demand of her under the circumstances. “And this ragamuffin?” she gestured at Pen.

“Pendragon Argent,” Friar Paul answered. Since none of them was quite sure what the boy’s future would hold given his precarious position as a ward of the ungenerous and unkind Baron Wrathdown, he finessed it: “His father was Lord of the Manor of Raheen-a-Cluig, attacked two days ago. He and a priest were the only survivors left behind.”

The better side of Mother Phillipa’s nature revealed itself in her look of genuine sympathy. “Poor boy.” She frowned. “He looks like he walked all the way here by himself.”

“He did, Mistress!” Char answered. “Lord Dublin said it was almost five miles past Shanganagh, which is five miles—”

Sindonie giggled, covering his mouth and shrugging apologetically before Mother Phillipa’s frown could turn into a complaint. “No one’s talking to you, Char!” she reminded him, and a couple of the children in the doorway grinned at one another. “And mercifully, the Archbishop let him ride in a carriage after his oh-so-long walk was over!” she concluded Char’s story for the benefit of the other children. They all turned their eyes appreciatively to the fine vehicle behind them, and the driver even managed to bestir himself enough to make half a gesture toward a smile and a salute.

“We’re not set up for gentle folk,” Mother Phillipa scratched her chin thoughtfully. “Why did the Archbishop send them here?”

Brother Paul shrugged, revealing all the truth before he even started talking: “Because you’re known as the Mother of All Dublin.”

“You’re a dreadful liar, Brother Paul,” Mother Phillipa blushed, unable entirely to resist the clever and charismatic young man’s charms, the girls behind her giggling. “I think your shrug was the better answer: ‘cause he has no idea what else to do with them.”

“Lord Wrathdown has committed Young Master Charles to the choir and the church, but the Archbishop felt he wasn’t quite ready—”

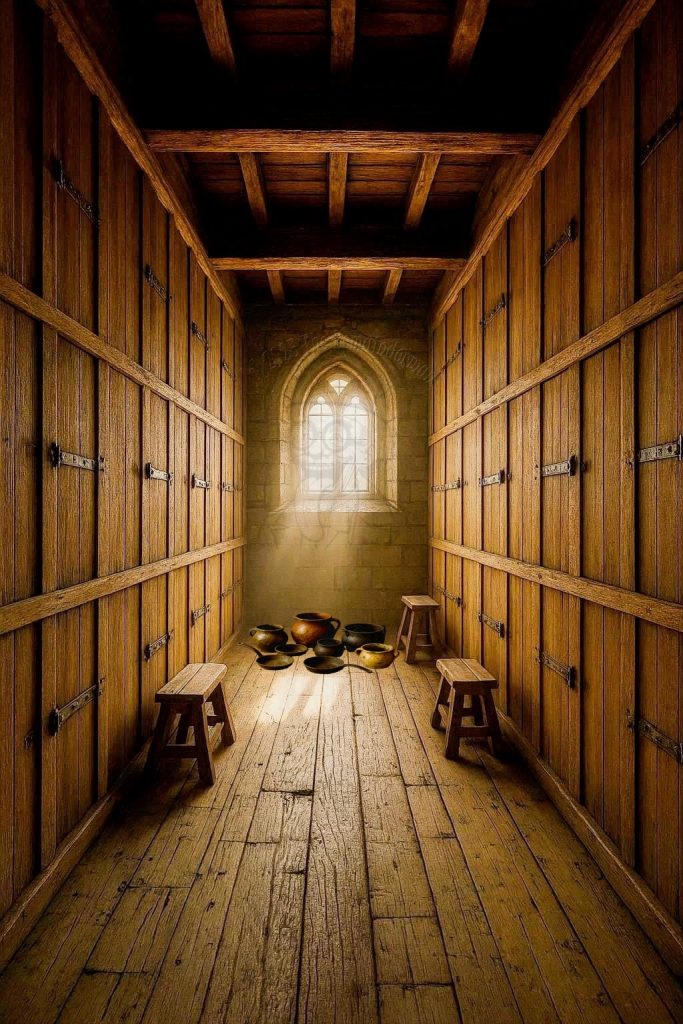

Mother Phillipa laughed, genuinely, at that. “You mean Father Adam would quit the Church before he’d accept underaged children he hadn’t personally vetted for his precious choir.” And in fairness, the boys’ choir of Dublin was a wonder to hear. “Well… I think we have a spare box they can share in the boys’ room,” she allowed.

Paul’s eyes bulged. “Er, the Archbishop had thought perhaps the Baron might expect a separate room for his son—” he began, breaking off because Phillipa’s laugh was so genuine and spontaneous, it obviously wasn’t calculated. And even the children started laughing. Friar Paul wasn’t sure what he’d said that was so funny, but he could tell there was something he didn’t know.

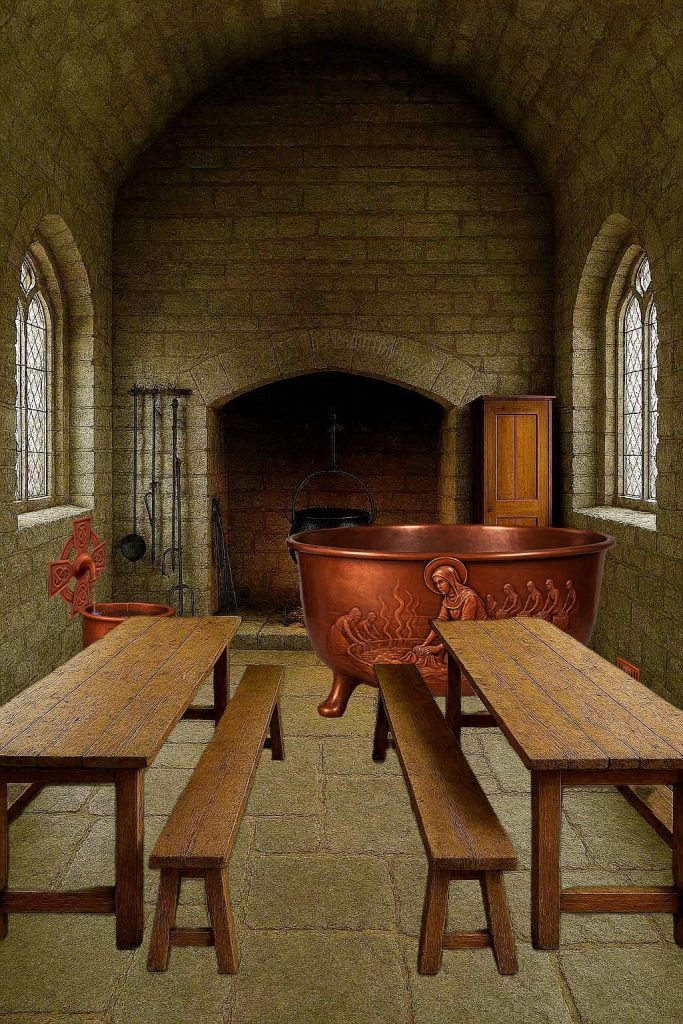

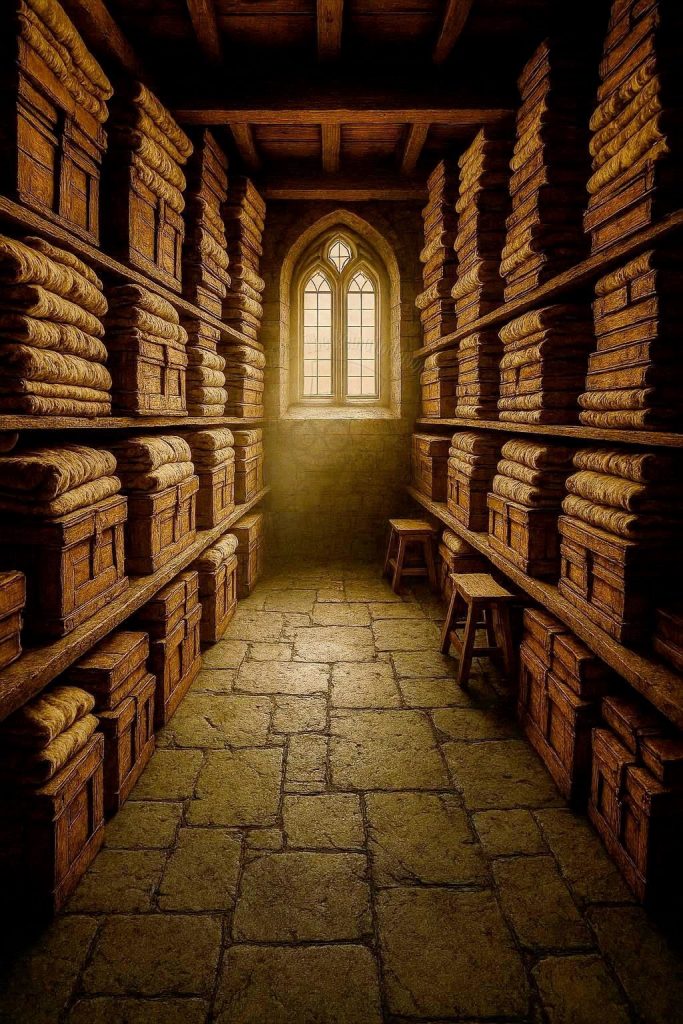

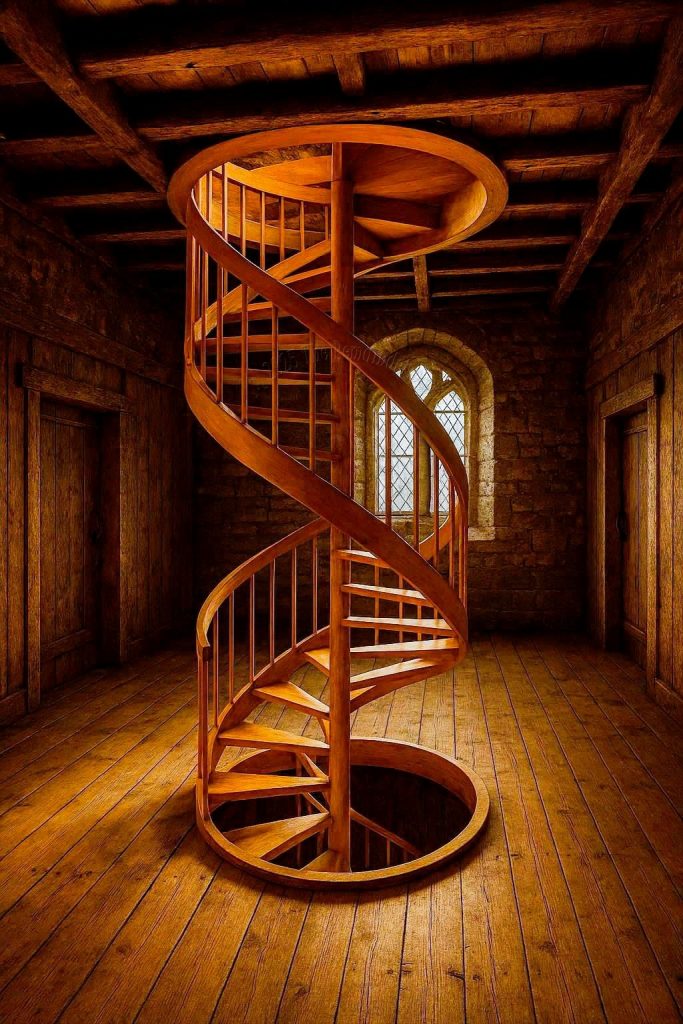

“We have exactly six rooms in our Hous: boys’ bedroom, girls’ bedroom, kitchen, schoolroom, storeroom, and matrons’ room. Which one of them did the Archbishop have in mind?” On a roll, and further encouraged by the solidarity of the children behind her, she suggested: “I’d suggest the storeroom. You know we actually store our own supplies in the other rooms, because you lot have filled the storeroom with the Church records? We had to borrow a ladder from the work-house so we could stack the records up to the ceiling, just so we could keep the floor clear,” she concluded.

Friar Paul opened his mouth, his eyes betraying how frantically he was trying to come up with a solution that would please the Archbishop, but Sindonie stopped him with a good-humored gesture and a glance, turning to Char and saying: “You’ve never slept in a box before, have you?”

“No, Mistress,” he shook his head.

“I’m told they’re ever so warm, and you’ll get to sleep with your friends!”

“You’re pretty!” One of the girls told Char. This made several of the boys snigger meanly. Unsurprisingly, given Char’s station, he did not immediately appreciate what that portended; and indeed, he didn’t even show any signs of embarrassment. It was difficult to read anything into Pen’s reaction; but Oliver, even as thick as he could be sometimes, understood it immediately. She was proud to see that it instinctively bothered him to see a boy he had grown up with, targeted that way.

“You could sleep in the girls’ room?” the girl suggested.

“Clemence!” Mother Phillipa growled, chiding her with more force than she felt, obviously thinking the girl needed it. As the other children laughed, she continued: “You girls are already packed in four to a box yourselves. And Christian boys and girls—English boys and girls—” she looked sharply towards three children standing together adding “boys and girls of Dublin—” (leading Sindonie to suspect the three children were probably from Irish families) ‘”do not sleep together unless they’re married!” Children being relatively guileless, there had been many times over the years when confused-looking children had protested and given examples from their own benighted childhood of unchristian relationships maintained right in front of them; but that wasn’t an issue tonight. She squeezed Clemence, mussed her hair, and told her fondly: “Charles will sleep with the other boys, where he belongs!”

Seeing that Charles seemed receptive to the adventurous idea of sleeping in a box, Sindonie turned back to Mother Phillipa and concluded proudly, as much for the benefit of the other children as for her: “My three boys grew up on the Pale. They’ve slept on the floor and carry their own knives like everybody else. A box will be perfectly fine. For them,” she emphasized.

“We have three beds in the matrons’ room,” Mother Phillipa responded to the suggestion. “With two sisters from St. Mary de Hogges on night duty, you’ll have to share a bed, but it should be quite comfortable.” Mother Phillipa then continued, raising a warning finger, “However, I can’t stand vermin, and I won’t have them in my orphanage! Most of these children come from the worst sewers and slums of Dublin and they come to us familiar with things that would make you turn white as a sheet. Things such as your little gentlemen there can’t imagine.” She spared the three of them a glance. “We teach them how to be Christians first, healthy second, and productive third,” she summarized their mission in a sentence. “And although doubtless these three little lords are pure and clean as fresh snow,” (her tone suggesting skepticism), “I can’t let these other children see me making any exceptions. Before any of you can sleep in this house, you’ll have to bathe and be checked for lice.”

“Well, if I must bathe, so be it,” Sindonie agreed, looking delighted at the prospect. “Please, show us the way. Oh—and where should these gentlemen put my trunk?”

“Third floor, on the right, for your trunk.” Friar Paul and the driver managed not to grimace at being volunteered for one final task before they could leave. The Archbishop had volunteered that Friar Paul could wait until the morning to return to St. Patrick’s and make copies of the letters; but the driver, and perhaps some poor stable hand awakened for the purpose, would have to care for the horses before he could go to sleep. The driver began unfastening the trunk from the roof. The treasure, of course—even the two harp brooches, which the Archbishop had promised to keep for Pen, reckoning they would simply be stolen in the orphanage—had been unloaded at St. Sepulcher, so Paul and the driver could wrestle Sindonie’s trunk up to the top floor without worrying about guarding the carriage.

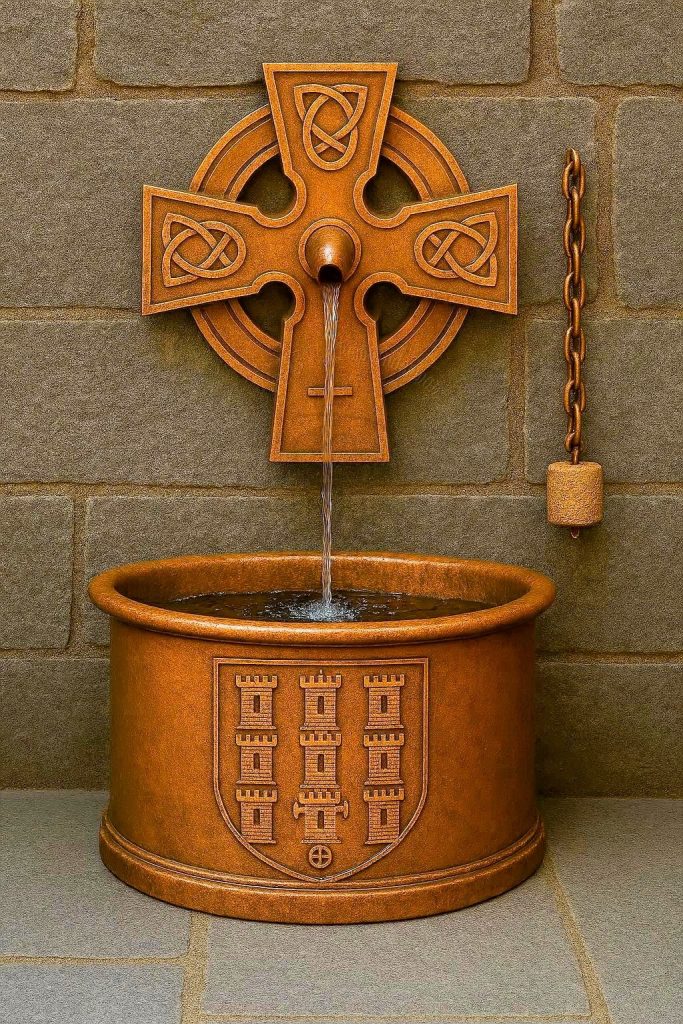

Meanwhile, Mother Phillipa was communicating to Sindonie: “And the bath is right here,” she gestured to the kitchen and dining hall, where they’d seen, and still saw, children looking out the window. “Next to the hearth, for heating the water; and the fountain provided by Lord Wrathdown.”

“The fountain?!” Char exclaimed excitedly, forgetting himself in his astonishment. “You have a fountain inside the house—Mistress?!” He added her honorific hastily at the end.

“Yes, thanks to your father, Lord Wrathdown,” she explained, interested but not surprised to see the boy didn’t seem care about the praise of his father; or perhaps, even to look slightly dissatisfied with her answer.

“How, Mistress?” the red-headed boy asked, his face filled with wonder.

Sindonie could see that Mother Phillipa was in no mood to answer questions from rude boys about things she couldn’t explain anyway; and was not accustomed to dealing with children who thought their questions and reactions mattered to adults. Heading off another potential problem for the sister, and, she hoped, demonstrating how valuable she could be if Mother Phillipa made her an ally, she gave his hand a squeeze and promised the boy: “That will require some investigation. But if you have patience, we can inquire and find out.”

“Yes, Mistress,” he agreed, seeming mollified.

Sindonie made Mother Phillipa’s evening, demonstrating both her practical knowledge and her work ethic, by pulling the curtains closed for privacy, heating fresh water in a clean cauldron over the fire, bathing all three of her boys, draining the tub, and tucking the boys into their box, without complaining, asking for any help or even advice, or even acting fussy and resentful like the two duty sisters. She thus allowed the other three women to get the other hundred or so children tucked into their beds as usual, wondering silently at the number of orphans in the Pale.

Without being asked, Mother Phillipa took it upon herself, as soon as the boys were sitting in the tub, to inspect each boy’s head very closely, even running a very fine comb through their hair before any of them washed it. She was looking for lice. And quite thoroughly, Sindonie thought, giving a mental nod of approval. But of course none of her boys were lousy, she thought loyally. Not even her new one. She made sure all three of them bathed thoroughly, confirming by observation that the new one had been well-enough raised to wash himself.

The boys’ bedroom was a narrow walkway, from the door to the central hall, to a hearth at the end of the building; with chamber pots and little footstools cluttering the floor, wooden walls on either side, and three rows of four double doors in each of those walls. Each set of double doors opened onto a box, about half as big as an adult bed. With 24 boxes total, the boys averaged about two heads per bed, although the biggest 4 or 5 boys seemed to have boxes to themselves, making for several boxes with three younger boys in them. The girls’ bedroom was just like the boys, but at the end of the building without a fireplace. Even if Phillipa hadn’t confirmed it earlier, Sindonie could have calculated the girls must be packed in twice as densely as the boys because they outnumbered them about two to one. Parents were more likely to keep boys and give up girls for the same reason the boys’ room was the one with the fireplace: because boys were valued more than girls.

When she brought her own boys up to bed, the other matrons were just getting the last of the other children settled. With a nod, Phillipa confirmed what Sindonie had guessed, that the empty box at the bottom with folded sheets hung neatly over the entrance, furthest away from the fire, was for the new boys. She saw Char start to get his back up and squatted down in front of him, brushing his long hair gently with her hand, explaining to him quietly, but with Pen and Ollie close enough to overhear her: “At the end of the day, Char-girl, you are as you were born, the master of all these other children, and you’ll enjoy the privileges that come with that. But you’re not in your father’s house any more; you’re in a school. And what you need to do in school—what every child needs to learn in school—is that you can be yourself and hold your own, even when you’re treated like everybody else. You need to take this chance to learn what these boys’ and girls’ lives are like by living the same way they do. Because they’ll be serving you the rest of your life, and you can’t manage them if you don’t understand them better. I know this isn’t going to be easy for you, honey. Some of these children are going to be mad at you.”

“Why?” Char asked.

She shook her head. “You’re an arrogant little shite, Char,” and she giggled at his shocked expression. “I saw you getting upset because you three got assigned the worst bed. These other children have all gotten the worst bed their whole lives, and they expect to go on getting the worst bed until the day they die, while you get the best. Try to imagine they see your father when they look at you, with—”

“I’m nothing—”

She put her fingers over his mouth and shook her head. “I’m not saying you are. I’m saying you look that way to them. You can be mad at them for that, it’s fine, but try to understand it too, and that they might feel about you the same way you feel about your father. Just—think about it. And I’m sorry you have to do this. But your father has sent us here to teach us the lessons he wants us to learn, and some of them are going to be hard. For both of us. But we’re going to learn them, and keep our heads high, so when we see him again he knows we’re tougher than him. Do you understand, sweetie?”

Char nodded, hesitantly, not entirely sure if he understood all of it or not. But thinking he did, a little bit. Especially the last bit. She tried again: “Your dad put us in this position. And I can’t make it too easy on you because you’ll need to face your father again at the end of this and show him what he expects to see. But I will get you through this,” she assured him, squeezing his hands tightly in her own and pulling his attention into her eyes, watching his lip tremble a little bit, even as he nodded sharply and decisively. She smiled proudly and hugged him, carefully making sure her head was against Char’s left cheek so that Pen, just to her right, would be able to hear what she said to Char: “And you’ve got Oliver here for the first few nights, don’t you? He’s going to be a big help, isn’t he?” Char pulled back, frowning at her, and nodded slowly as they shared a secret smile that Pen saw. She kissed him and hugged Pen before turning and hugging her own son and whispering what she wanted him to know: “I’m going to come check on you after my bath. Do what Sister–Mother Phillipa tells you, take care of the other boys, and if anything happens, I’ll help you sort it out then.”

“Yes, mom,” he answered. She didn’t quite know what he understood. She never did. It broke her heart to even think it, but she knew her son wasn’t quite what other children were in some ways. He was as simple as he was big for his age. But he could hold his own when he had to. And she knew he trusted his mother.

Pulling all three of them in close, she whispered: “I want you to behave here, and treat Mother Phillipa with the utmost respect. But when you’re alone with the other children, you may need to worry about them first and accept the consequences later.”

“Yes, Mistress,” the chorused, ranging from confused—Pen—to determined (Char) to simply accepting (Ollie).

“Good night, boys. Good night to all of you boys!” she said to the room, waving gaily, getting responses from many of them before walking out.

She had noticed that each of the little boxes had a latch on the outside, presumably allowing the matrons to lock misbehaving or problem children into their beds. Frowning thoughtfully, and hiding a smirk, thinking that was a terrible idea if children in Dublin were anything like children on the Pale, she returned to the kitchen below, rinsed the tub, drew her own bath, and hummed quietly, reveling in it. She almost imagined she could hear the matrons leaving and going to their own room. Then, she almost imagined she could hear thumping and crying from the boys’ room; but she wasn’t really quite sure. As much as Dublin City shut down after curfew, the human sounds never really stopped here. And like many buildings belonging to the church, this one had been built to last, muffling the sounds from other rooms as much as it did the sounds from outside.

A bath with a faucet, fire, and drain in the same room? She marveled at the idea. She’d never imagined anything so luxurious. She might have to treat herself to a bath every night! She had been to Dublin before, and knew at some level water was brought into public fountains in the city; but she had never heard of a building with its own water supply before, not even a castle or a palace! Not that she’d even been to a palace, or even a truly prestigious house, before. There were nobles, and there were nobles. Here in the Pale, there were the City and some of the county aristocracy who thrived on trade and large estates; and then there were folk like hers, marcher folk or folk like her mother, who came from gentry so humble they looked for opportunity out on the frontier. The Royal Court in England? Well, that was something she’d heard about, but couldn’t really imagine.

She snorted, amused at herself, lying with the towel Mother Phillipa had provided, and that she had already used to dry the boys covering her eyes, feeling for all the world like the Queen, unable to believe Catherine of Aragon could actually feeling any better or more fine than she was on this night. Sindonie stayed in the bath until the water started to cool. Pulling the plug out so it could drain, the water rippling down to the lowest part of the floor where a drain at the bottom of the wall let it escape to lower Bothe Strete on the downhill side of the Charite Hous, she quickly splashed fresh cold water on the tub and scrubbed it with some rushes to clean it. Then, after a moment’s thought, she refilled the big cauldron a third time so the water could heat over the embers that were still fierce, but no longer flaming. Wrapping the big warm towel around herself, she brushed her teeth, enjoyed a handful of fresh water from the fount, put the cork back into it (and laughing when, inexperienced with such things, she was too slow pushing the cork in and sprayed herself with a brisk wave of cold water), before bouncing up the stairs to the second floor.

Quietly, she opened the door a crack and peered in, squinting in the dim light until she was sure. As she had expected, the latch on her kids’ box had been snapped home, trapping them inside. She snorted. “Little sarding shites,” she hissed to herself, smiling, knelt on the floor in front of the door, and opened it, blinking to speed her eyes’ adjustment to the even heavier darkness inside the box.

She snorted again and shook her head, teasing the three of them gently, speaking loudly enough for all the listening boys around the room to hear: “You three look like a litter of sad little puppies.” And they really did.

Giggles and snorts came from the other boxes, at the expense of her boys; but she couldn’t quite help seeing the humor in it, either.

“They—” Char began, and she silenced him by putting her own finger over her mouth, making sure both Char and Pen got the message, even as she said—while shaking her head—“I don’t want to hear it!” Then she crooked her finger at Oliver and helped him silently out of the box. When Char tried to follow, she held up her hand, smiling and nodding encouragingly, and put her finger over her lips again.

Not entirely happily, but trusting her, Char settled back down on the mattress, and the watchful Pen simply waited silently with an expression of uncertainty.

“I’m glad I checked on you,” she said in her stage whisper. “I’m leaving this unlocked and I want you silly boys to leave it unlocked in case you need to pee. Do you understand me?”

“Yes, Mistress,” the three boys chorused.

“Good night,” she sang, and as they answered her, she shut the door of their box before pulling Oliver by the hand out of the room with her. She closed the door to the hall most of the way, just leaving it cracked, and indicated to Oliver he could peek through the crack, while she stood behind him, petting his hair.

For a few minutes, nothing happened. Then Oliver tensed in excitement, presumably seeing what Sindonie had expected. A moment later, she heard snickering at the same time a bolt—doubtless, the latch on the box Char and Pen were trapped in—slid closed.

“Hey! Hey!” she heard Char’s muffled protest, and louder laughter from several boys. Oliver looked at her for confirmation and she gestured for him to do whatever he was going to do. Like a dog released into a pen filled with rats, he threw the door open and raced in, too busy and focused to make any sounds besides some natural growling and grunting. The other boys were much louder, crying out in surprise and then protest, rage, complaint, pain, and fear, generally but not entirely in that order.

Oliver was eight. The orphanage was intended for children seven and younger; but as the Archbishop had explained the previous day, there were older children—by their appearance, she guessed up to eight or nine or even ten—who still resided here because there was no place for them to sleep where they apprenticed. She guessed several of the bullies—it sounded like there was more than one of them—were probably Oliver’s age or older. Oliver was a bit big for his age, but it wasn’t really his size that made the difference. It was the intensity and focus he had about things he took seriously. And maybe a little something else, Sindonie suspected sometimes. There was a brief pause in the sounds of struggle when she heard what she presumed was Oliver unlocking the box to liberate his friends, and she beamed with pride that her son gave them a thought even in the midst of battling others.

When the door of the girls’ room opened behind her, Sindonie looked back over her shoulder and saw what she expected: a bunch of girls, already out of their boxes and shivering in their colder room, wide-eyed. When they saw her, they almost closed the door again but she just grinned at them and ambled over to the boys’ door, opening it so they could all see the fight transpiring there, and leaning against the door frame, crossing her legs at the ankles, her feet cold on the floor and her wet hair cold on top of her head. But Mother Phillipa had only laid out one towel for all four of them to share, and she had to use that around her torso, not only to avoid shivering, but for modesty! So she brought her arms in tight to try and stay warm as she watched the expected scene playing out in front of her.

Ollie was mowing through all opposition. Char and Pen had jumped out to support him and, being younger and gentler, came out on the worse end of every exchange with any of the other boys. Still, they felt obliged not to abandon Ollie, and acquitted themselves nobly if ineptly. In the big scheme of things, it didn’t really matter; Ollie was all that mattered, and all that was necessary, for the victory; Char’s and Pen’s sole function (although they were probably too young to understand it) was simply to demonstrate loyalty and courage to the other boys.

Honestly, it went on longer than she expected. Not because Ollie disappointed, but because the other boys were tougher than she might have given them credit for. The bullies who’d come out to torment had stayed to fight, hanging in there even as they took a drubbing, just as Char and Pen were doing.

She braced herself when she heard heavier feet slapping on the stone stairs behind her.

“WHAT IN THE NAME OF ST. EDMUND IS GOING ON HERE?!” Mother Phillipa demanded as she launched herself off the stairs, jumping over the last three or four steps and landing on the wooden floor, surprisingly nimble for a woman of her bulk.

With a burst of gasps and panicked noises, the door to the girls’ room closed and Sindonie bit her lip to keep from laughing as she imagined how they must all be slithering back into their boxes and pretending to be asleep.

With great difficulty, Sindonie wrestled her features into a semblance of seriousness, managing to look a bit lost and unsure by the time Phillipa came even with her, giving the impression of a woman who had never come across anything like the scene in front of her before and didn’t know what to do about it, rather than an instigator-in-chief laughing her ass off at the chaos she’d stirred up. But if there was anything she understood, it was boys. Char and Pen were going to get their asses kicked here at Our Ladies. It was for the best they should do so while Oliver was the center of attention so the two weaker, lesser boys could demonstrate that even if they were wimps, they were not cowards. And having Oliver fighting by their sides made it much more likely they would, in fact, demonstrate bravery. Being outnumbered and overpowered at the same time, with absolutely no hope of resisting and absolutely no allies, had a way of encouraging cowardice. That was not what the other boys needed to see from them.

“Mistress Manning—what?! This is unacceptable!” she screeched, charging into the boys’ room in only her nightdress and nightcap, followed by the two duty nuns from St. Mary-de-Hogges. One senior boy was sitting on Char, holding his hands down over his head with one hand and punching him in the face with the other. Two senior boys were wrestling with Pen, who was putting up a surprising fight; but then, the boy was probably half-wild and half-crazy after the events he’d witnessed in the last three days. Meanwhile, Ollie was, in a more-or-less leisurely fashion, continuing to toss seniors and boarders into walls, knocking them down to the floor, and yanking them furiously by their hair as they squawked and cried out in surprise.

The mere sight of Mother Phillipa, somehow twice as terrifying dressed like a wild Irishwoman in bare feet, nightgown, and nightcap than in her usual neat uniform, was enough to send virtually everyone other than the primary culprits scattering back into their holes as quickly as they could get there, hoping that if they could disappear fast enough, they and their transgressions would be forgotten or overlooked. And even the real instigators and their three victims shrank back and fell passive at her sight or touch. The other two nuns weren’t exactly idle, they just weren’t all that effective, either; lacking both Phillipa’s authority and conviction. When they seized boys by their shoulders, the boys so seized would quiet down and look guilty the instant they saw who they were dealing with, even before the sisters started swinging their arms.

And none of the three nuns were shy about that: Phillipa slapped Pen so hard his eyes shot wide open and he practically came to attention, looking startled and starting to apologize profusely and sincerely. So much so the nun realized he’d been dealt with with a single blow and she could turn her back on him and move on to the next. One of the others put one hand on each of two boys attacking or approaching Char and pulled them off him, slamming them back and holding them pinned against opposite wooden walls for the few seconds it took them to calm down, come to their senses, and slump into submission.

Ollie, she was happy to see, saw Phillipa before she even reached him and withdrew from combat, hanging his head in resignation and accepting a final flurry of blows from his opponents without really reacting at all. Which made them feel really stupid, that they could be fighting him with all their energies while he quit, essentially showing them they didn’t matter at all to him, and he didn’t even need to fight them to hold his own.

It didn’t take Phillipa more than a few seconds to shock and subdue all of Ollie’s opponents; and after she did, there was a second—just a second—of silence and stillness while Phillipa took a deep breath and forced herself to relax. Then she turned to Ollie and the two biggest and oldest boys in the room, who had been fighting with him: “What happened here?! Where’s Roger?!”

All three boys stood silently, looking down at the ground.

“I asked what happened!” Mother Phillipa shouted. With enough presence of mind and self-control it was clear she was in in control of herself and determined to get to the bottom of things, not giving into her likely anger and frustration.

“Answer her, Oliver!” Sindonie commanded, similarly assertively but not angrily, softened by the genuine love she felt for him.

“I’m sorry, Mistress,” Oliver answered. “Someone locked us in our box.”

“WHAT?!” Mother Phillipa screeched, genuinely shocked, the fact she was actually upset having an electrifying effect on the children in her care.

“My mother—Mistress Manning—unlocked the door and checked on us some time later and as soon as she left someone tried to lock us in again. So, I stopped them.”

“You mean you attacked them!”

“Yes, Mistress. I’m sorry, Mistress.”

“Who was it?!”

“Ahh…” he hesitated, looking around from face to face. “I’m honestly not sure, Mother Phillipa. It could have been—was probably one of these fellows,” he said, gesturing vaguely at the older boys around him, “but I can’t really say.”

“Cutter!” she shook one of the older boys, a mean-faced sullen fellow with spiteful black eyes and enough black hair for a horse. “Exactly what I would expect from you! But where has Roger gotten to?”

Cutter didn’t answer, even when she pinched his arm brutally and insisted: “Tell me!”

One of the other boys broke at a glance from the nun and whined: “Hard Henry locked him in the cellar overnight for talking back!”

She signed, taking a moment to digest that, seeming both saddened and accepting of it as a necessary fact.

“And YOU!” Mother Phillipa rounded on Sindonie, shoving her harder than she had intended, enough for her to fall back against the door frame and have to grip it for balance to avoid falling over. “What kind of tutor—what kind of mother—” she broke off, taken aback by the way Sindonie’s pupils dilated and she breathed a little bit heavier, not a reaction she had expected or was quite able or willing to interpret.

Taking another deep breath, Sindonie explained: “The border. I—”

“What?” Phillipa was honestly confused.

“We’re Pale folk. From the frontier.”

“And this is how you–?”

“More or less,” she nodded, spreading her hands and shrugging. “Of course. This is exactly how we do it. We settle things. Don’t you?” And when Phillipa’s incredulous face communicated that, no, they did not think the same way, Sindonie shrugged. “Maybe the barricade just makes it obvious. The lines are clear. Everything gets clarified.”

“‘More Irish than the Irish,’” Mother Phillipa shook her head, shocked. “I’ve heard it said all my life, but I never—really—understood. But it’s not the way we do things in Dublin. This is a proper English city.”

“I’m sorry, Sister–Mother,” Sindonie apologized. She was still breathing a little too heavily, and while Mother Phillipa didn’t quite understand it, she was definitely unsettled. But she seemed quite sincere, and Phillipa had seen how genuinely she was proud of her boys. A little parental affection and care went a long way with a woman who spent her life trying to repair the damage done by people who viewed their own children as nuisances. “We’ll figure it out,” Sindonie promised earnestly. “I swear it. I’ll do better.”

“You’re like barnyard animals! This is Dublin City!”

“We’ll get used to it, Mother. Please! Give us a chance.”

Her face softened. “Of course, I’ll give you a chance. I’m just not sure that will be enough. Get out—all three of you, go on, get to bed.” And she turned back to the roomful of tired, scaped boys around her, as the other three matrons left the room. “Nothing like this has happened since… I don’t even know when, and I promise you it will not happen again in your lifetimes! I’m too angry right now to punish you, but in the morning, I’ll make sure none of you ever forget this was the worst mistake you’ve made in this house,” she assured them, sending a shudder through the room. (And she qualified her threat mentally: If you didn’t count the times various children had nearly burned the building down around them, mishandling or even trying to play with fire. But it wouldn’t help any of them to share that thought with the children.). Instead, her tone softening, she changed her focus. “First things first tonight. Are any of you idiots seriously hurt? Does anyone need attention? Cuts? Broken bones? Pain?”

Outside in the hall, Sindonie stood at the foot of the stairs, blocking the two duty nuns until they came up short, their eyes widening as they realized she was intentionally getting in their way to force them to heed her. “The big bed next to Sister-Mother Phillipa’s is mine,” she announced quietly, but convincingly. “Tonight, and every night. You two can share the small bed against the wall opposite Mother Phillipa.”

Both of them glowered at her, and the larger of them—taller and bigger than Sindonie—sneered and stuck her jaw out. “No, that’s my bed, and I’m going back to it. Don’t try to stop me.”

Sindonie stepped right up to her, looking almost vertically up into her eyes. “Mother Phillipa sent you two to bed, so go to bed. Just not my bed.”

“She sent us all to b—she told all of us we could go to bed,” the nun corrected herself.

Sindonie smiled, like a wolf, with eyes that held no trace of any friendship or levity: “She sent you to bed. And now I’m sending you to bed. Your bed. The small bed the two of you are sharing. If I find you in my bed, I’m going to choke you out and then roll you out onto the floor when you’re unconscious.” Smiling wider, she let her towel drop to the floor so she could ball her hands into fists at her sides, pushing forward naked and ornery into the larger woman, shoving the top of her breasts into the bottom of the other woman’s. “And if you don’t want to do what I say, right now, we can handle this the Pale way. You know what you have to do. So either prove you’re the boss, or go to your bed.”

The woman’s jaw worked for a moment, while her fellow Augustinian looked at her, both their expressions revealing the same shock and confusion. Ultimately uncertain how else they could handle this mad woman, she shook her head and growled: “You’re not worth it. Tomorrow night I’ll be back in my own cell, and you’ll still be here, doubtless challenging the next duty nun. You crazy bitch!” She concluded, both of them circling warily around the smaller woman and hurrying up the stairs, leaving a bit of their dignity behind but keeping their common sense a great deal better than Sindonie.

The frontier woman wrapped herself back in her towel before Mother Phillipa came out of the boys’ bedroom, pulling the door shut and then turning around, surprised to catch sight of Sindonie.

“What are you doing, still down here?”

“I have a gift for you.”

“What?”

Sindonie tried to encourage her to go down the stairs. “It’s already done. I know I’ve made a mistake—”

“No, I’m too tired—”

“Please.”

“Augh! Fine, for one minute, you vexing woman!” she agreed, unhappily following Sindonie down the stairs into the kitchen.

“How long has it been since you’ve allowed yourself a relaxing bath at the end of a long day?”

“I don’t take baths to relax!” she protested, trying to turn back around towards the stairs.

“No—please—I want to do this for you,” Sindonie insisted, pushing the kitchen door closed and using the same physical blocking tactic she had with the two sisters upstairs, but with less open aggression. “I’ve upset you and made a bad impression on our first day here and I want to show you I’m committed to this, to you and to the children in my care. I want to learn!”

“You can learn tomorrow! I have to think how to handle what you—what happened—”

“You know how to care for this houseful of children—” Sindonie laughed “this house bulging with an army of children.” Mother Phillipa couldn’t help but acknowledge the truth of that.

“I know how to take care of weary soldiers.”

“I’m not a weary soldier—”

“You so are,” Sindonie disagreed, using the bucket to draw hot water from the cauldron and pour it into the bath.

“I don’t need a bath.”

“You don’t need to wash,” Sindonie corrected her, noticing with satisfaction how longingly Mother Phillipa’s eyes lingered on the big tub she was filling with hot water. “But you need to let yourself be cared for. You care for every orphaned child in the Pale. Who cares for you?”

“God cares for me,” Mother Phillipa answered, meaning it, but unable to avoid the truth of Sindonie’s next statement:

“Which is true, but in context, means you can’t name a single person who does. We have to care for one another in this world. Especially we women. If we’re going to wrangle children side by side in the same house, we need to care for one another, and having caused you such difficulty tonight, difficulty I know you will still be dealing with tomorrow—please!” Sindonie suddenly urged her, giving up. “Please, I can do this. Let me apologize.” She fell to her knees before Mother Phillipa, looking up at her earnestly. “I beg of you.”

Mother Phillipa’s resistance collapsed. Defeated, she sighed. “You’re terrible,” she complained, rolling her eyes and taking off her cap.

“Thank you!” Sindonie bounced to her feet happily, leaning over the edge of the tub to dip her elbow in it and test the water temperature, deciding to add two buckets of cold water, then testing it again and adding another bucket of hot, before nodding with satisfaction and holding Mother Phillipa’s arm to steady her as she climbed into the tub.

“I’m not feeble!” she protested. “Oh! That water is perfect!” She sighed. “I haven’t heated bath water for myself in… so long.”

“You take cold baths?!” Sindonie asked in astonishment. Then amplified: “You take primary care of a hundred wild orphan children in a cold stone six-room converted… whatever this place was built for, clearly not this!” And she laughed, seeing the smile start to play around Mother Phillipa’s face, seeing her muscles start to relax and her eyes close as she lay back against the back of the tub. “Helped only by a handful of resentful women who don’t like children—”

“Maybe,” she conceded, sounding embarrassed. “A little bit…”

“On the wild, wild Western frontier of England,”

“Well… yes…”

“And the only thing you have that any covetous person would envy is a copper bathtub next to a cauldron in the only room I have ever been in or seen or even heard tell of, with running water….”

“Fine!” she was laughing now, shaking her head with her eyes closed. “Yes!”

“And you give yourself quick ice-cold baths to avoid any possibility of time off or pleasure for yourself so you can hurry back and start giving warm baths and warm meals and attention to your hundred orphans?!”

“I’m a nun!” she laughed.

“You mean you’re a zealot,” Sindonie laughed back.

“I’ve dedicated my life to God, not to my own pleasure.”

“The Bible doesn’t say we have to be miserable. It doesn’t tell us to hurt one another, but to care for one another. This is more comfort than pleasure. Surely it’s good for us to give comfort to one another?”

“I suppose…” she admitted reluctantly. “It’s just…. It’s just…” but she couldn’t quite figure out how to finish the thought.

So Sindonie finished it for her: “It’s just, neither you nor anyone else has cared for you in so long, you don’t even remember what that’s all about.”

“Maybe,” she laughed. “Wait! What—”

Sindonie stepped in the tub and sat down, in the other end, facing her, giggling at the water sloshing over the sides, the innocence of her joy in the splashing water reassuring Phillipa. “This is care. This is human love, following the example of Christ our Lord. Just as the Royal Almoner himself does on Maundy Thursday,” she observed, taking hold of one weary foot. “Don’t try to tell me this is wrong,” she cautioned Phillipa, giving her a sharp look. “Not when we know literally Christ taught us to care for one another this way.”

Phillipa bit her lip as Sindonie began washing her feet.

“No. This has to be wrong. I don’t know how—it just has to—”

Sindonie snorted. “Smart Christians can be so stupid sometimes. Tomorrow, when you’re figuring out what to do with all the dumb boys, and remembering how angry you are at me while you’re picking up the pieces of the mess I made tonight, I’m going to remind you of this and ask you how it’s Christian to be mad at me for my mistakes—”

“I don’t want to think of that now!”

“—but not be grateful for my love. Oh, wait: You don’t want to think about that, but you don’t want to relax and enjoy yourself? What do you want?”

“I don’t know!” she shook her head, laughing. “You’re very vexing! I—I—” suddenly she gasped, opening her eyes and her mouth and looking straight at Sindonie.

“Whaaaat?” Sindonie asked uncomfortably.

“I know what I want. Not, I mean, in life. Well, maybe in life. Maybe it is what I want. But what I mean is, I know what I’m feeling anxious and worried about now, as you wash my feet in this tub—ohhhhhhh I’m pretty sure that must be sinful… it feels like what I imagine a certain—kind of sin—feels like—”

Sindonie burst out laughing. “You don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“I think I do!”

“I’ve been married. I have a child. I know exactly what you’re talking about.”

“Okay, fine, you know what I’m talking about,” she giggled, embarrassed.

“But you obviously don’t,” Sindonie laughed again.

“Of course not!” she protested.

“But tell me what you were going to say.”

“I don’t remember.”

“What you want?”

“Oh. Yes. I want things to stay simple. To be simple again.”

“Simple?”

“Yes. Like they were yesterday. Like they’ve been for a long time. Even if they’ve been boring. Even if it meant taking in another three boys without any more help. It felt… safe!”

“And… what, I’m not safe?”

“Oh, absolutely not!” Mother Phillipa laughed. “I could tell that the moment I set eyes on you.”

Sindonie didn’t know what to say, because she kind of knew she was trouble. So she just smiled a quiet little smile to herself.

“And you’re not simple.” And when Sindonie still didn’t say anything, Phillipa prompted her: “Are you?”

Sindonie had to burst out laughing, shaking her head. “No. No! I’m not simple.”

“Nothing about you is simple, is it?”

“Probably not one thing,” Sindonie admitted, gently switching between feet in the warm water. “I’m not simple. None of my boys are simple—well, I mean, in the way that you mean. I should say, there’s nothing simple about them. And there’s not even anything simple about the stupid Baron’s stupid plans—” they both laughed, Phillipa accidentally making a snorting sound she was so delighted to hear someone else express what one assumed, and in a most un-Christian fashion probably hoped, everyone thought—“Don’t get me wrong: his plans are stupid, they’re always stupid, but they always wind up making a complicated mess of everything for all of us….”

They both fell silent, reflecting on the very long, difficult day they had both just had. And because they were facing one another eye to eye, it was easier to sit and enjoy a moment of silence with their eyes closed, looking inward upon themselves, reflecting on the complexities of the day or the simplicity of the bath.

Perhaps it wasn’t surprising they both fell asleep right then and there. And fortunately, or by God’s grace, the cooling water woke them up again, long before anyone else was stirring in the house. And the snoring coming from the small bed on the other side of the matrons’ room reassured them neither of the nuns from St. Mary-de-Hogges was snooping on them or minding their habits.

Literature Section “08-03 Our Ladies of Lesser Mercy Mary Magdalene and Salomé”—more material available at TheRemainderman.com—Part 3 of Chapter Eight, “The Wild, Wild West”—8515 words—Accompanying Images: 4539, 4553-4564, 4585-4598—Published 2026-01-15—©2026 The Remainderman. This is a work of fiction, not a book of suggestions. It’s filled with fantasies, stupid choices, evil, harm, danger, death, mythical creatures, idiots, and criminals. Don’t try, believe, or imitate them or any of it.