PREVIOUSLY: Two traumatized boys residing on the militarized Southern border of the Pale, Char and Pen, accompanied by Char’s governess Sindonie and her son Ollie, have just been given into the care of “Mother” Phillipa and the Augustinian nuns who operate Charite Hous, the only orphanage in the Pale. In their first 12 hours at the orphanage they have fought, talked, and been beaten with their new fellows. And after doing her best for her charges, Sindonie must also think of herself. NOW:

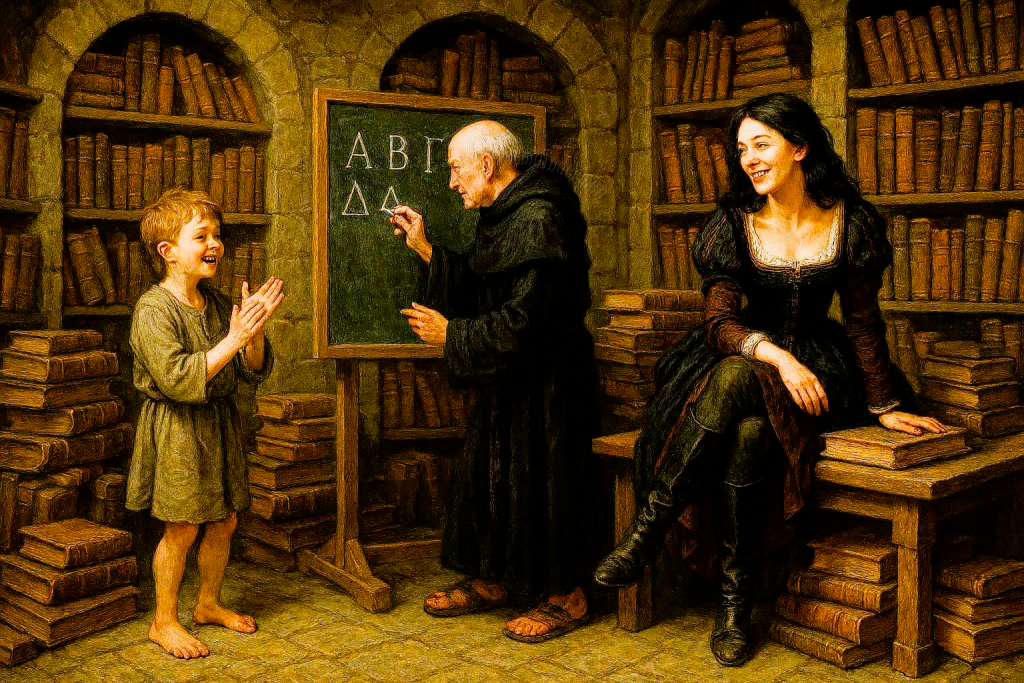

Their first day of classes—after the regrettable beating that began the morning—was a success. Oliver was not too interested at first, but started to enjoy what was—for him—strictly a refresher course in letters, counting, and English when his mother proposed a game: Oliver playing the teacher. The boys seemed to find it hilarious, and Sindonie, with the germ of an idea, or perhaps a concern, in her mind, very consciously encouraged Char and Pen to help Oliver teach themselves.

In the afternoon, Sindonie and Brother Griffin agreed there was little to be gained by making Oliver sit through a few hours of Greek before returning to his knight training. He agreed Sindonie could give him the run of the parts of Christ Church and the Holy Trinity Within that were accessible to the public.

Sindonie wasn’t that interested in Greek, either. But she knew she would need to understand at least a bit of it to help the boys and be effective in her job. It also crossed her mind that rarity was a source of value, and if Brother Griffin was the only person in Ireland to know ancient Greek, it implied there could be some value to the knowledge. With somewhat muddled purpose, she endured the first day with Char, the two of them exchanging dubious and skeptical looks every time Brother Griffin said something that sounded weird—which was pretty often, since he seemed to be suggesting that Latin—which both of them knew already, and they had been taught was the language of the Bible—had actually developed after Greek, and that parts of the Bible had been originally written in Greek, or translated to Latin from Greek, even if they had originally been in Hebrew or a language Char and Sindonie had never heard of before called Aramaic.

For some reason, Char seemed to find it particularly funny that “P” turned into “Rho” and Psi looked like a candelabra. Sindonie tried to keep both of them engaged in the lesson with Pen, without frustrating Brother Griffin too much. She could tell that sometimes, he seemed to positively want to find problems with the idea of teaching their motley crew Greek—she thought it was because it upset some very fixed and fusty old notions of propriety he had—while also finding that he was excited and enjoying himself, even if he wasn’t prepared to admit it. One sight of poor Char’s back, bottom, and thighs (Sindonie checked his bandages and wounds after every divine office), and Griffin seemed to get a lot more sympathetic towards the boy, showing him great patience, even impressed with him for being able to show any kind of interest or demonstrate any degree of concentration when he was suffering so much.

When they were finished, Sindonie, somewhat nervously, was thinking about the least-suspicious ways to propose that Char and Pen search the cathedral and other churches while she search the remaining areas. But mercifully, when they exited the library at Holy Trinity Priory, they found Oliver in the cloister, crouched on top of a square plank, helping a skinny, middle-aged man in the robes of an Augustinian religious brother who was sawing the end of it at a 45 degree angle along a diagonal line from corner to corner.

They all watched curiously, not wanting to interrupt until the task was complete. After sawing the last of it, the brother scanned the surface he had just cut with a critical eye, finally nodding with a begrudging respect. “What do you think?” He asked Oliver.

“Very smooth, Friar James; but I think it still needs to be sanded… here….” Oliver pointed with fingers of both his hands, indicating a region of the cut.

“Your eye is as steady as your hand, young man. I would suggest wood should always be sanded after cutting, as a matter of course, when you’re talking about weight-bearing architecture and decorations for a religious building. And I like to make everything I build as close to perfection as I can as a mere human. We are working with the body of living things, the trees. And it makes me feel like—” He looked up toward the sky, as if seeking inspiration there, instead spotting the boys and their governess. “I am following as closely as I can, in God’s footsteps,” he finished, and then smiled at the new arrivals. “I’m Brother James, the Priory carpenter.”

“It’s so amazing, mother!” Oliver positively gushed—for a child as calm and reserved as Oliver usually was— “Look how he cut these two lengths of wood… just here… with these sharp angles, so they hold together, even before gluing the wood!”

“That’s… very impressive,” she managed to nod, hoping she sounded half as enthusiastic as she was trying to.

“No one does that in Wrathdown… or Skremen.”

“I’m sure they don’t,” she agreed, smiling back at Brother James. “Thank you for showing this to my son.”

“It’s my pleasure and duty,” the brother assured her. “Carpentry is the Lord’s work.”

She gave him a sharp look, decided he understood what he was saying was funny, and smirked until he smirked back. “So it is,” she allowed. “Will you be working here again tomorrow?”

“For several more days, I expect.”

“Then we may see you again.”

“I hope so!”

Midnight. Or so said the city watch, passing by in the street, scaring her senseless.

She had awoken in a cold sweat, gasping with fear at the nightmare visions of burning and branding and hell that she had suffered.

She forced herself to lie still for several minutes, confirming she heard the steady breathing of Mother Phillipa and at least one of the two duty sisters sharing the third bed.

Quietly slipping from her own canopy bed, and carefully pulling the curtains closed behind her to discourage anyone checking on whether she was there, she crept to the door—which fortunately, Mother Phillipa left open at night to better hear any disruptions like the one that had brought her running the previous night. She moved silently to the stairs and down them, 1-2-3-, willing them to be silent. She chided herself for not having paid any attention to noises on her previous transits up and down the stairs as each step was another exercise in suspense: 4-5-6-7-she-skipped-8-straight-to-9-and-then-cringed-as-she-landed-on-it-with-a-slight-noise. Freezing and making a face, she eventually resumed her downward circle, waiting for one of the wooden landings to surprise her with a creak or squeal she might not have noticed in the chaos of daytime at the orphanage, but that might sound like a thunderclap in the silent night. But she dared not to try and skip any more steps in the dark.

Her next scare came just after passing the second floor, on stair number 20: she heard a creak. She was sure of it! And not from the 20th stair: from somewhere behind her, which meant the second or third story and maybe—if she trusted her instincts enough—from the boys’ bedroom.

She tried to persuade herself she wasn’t nervous as a cat because she was afraid of getting caught; why should she be? At this point, only she knew what she was about; and no one had told her she wasn’t allowed out of bed.

Yet! But if she had to bet, if she were caught, Mother Phillipa would be suspicious (she barely, well almost, stifled a giggle as she thought: although why on Earth she would suspect little old lay sister Sindonie, or whatever she was, for creeping around at night the second night in a row after being, er, linked at least to the terrible fight that had erupted, she couldn’t imagine….).

“Stop being silly,” she whispered to herself unhelpfully; but as certain as she was she’d heard something, it hadn’t been repeated. And really, who would be likely to wait silently longer than she had just done? None of the children had the patience; and she was more than 100% certain any of the three nuns upstairs would be curt, rude, and extremely impatient with her or anyone else they found wandering around in the dark.

Finally, her fear of loitering so long she lost her chance, overcame her fear of being caught; and she continued on her way down to the ground floor. Eventually, 36 long stair steps after commencing her progress at the top, she reached the bottom. It was there, three steps away from the staircase, that the complete and utter silence was suddenly pierced by the watchman in the street, hollering out as loudly as he could manage: “Twelfth hour and all’s well! The King’s Peace is unbroken, the night is cold, and the sky is clear!”

She clenched, she tensed, a expletive hissed halfway out her lips before she caught it and sucked it back in, her body still surging with the wave of adrenaline the cry had triggered. Who the sard thought it was a good idea for the city watch to be screaming out anything in the middle of the night, let alone the time and weather?! And, wouldn’t silence be a better way to demonstrate, even celebrate, the king’s peace being intact than hollering about it and waking people up? Despite being muffled through the heavy front door, when unexpected and coming out of total silence one had no reason to expect would be interrupted, it sounded LOUD!

She tried to count herself lucky these were just the regular watchmen, and not the waits—she had heard Dublin had them, like any civilized city back across the Irish Sea—singing and playing music as they wandered through the night streets like madmen playing pranks on sleepers.

She bolted to the storage room, and with a tiny squeaking noise, eased the door open just enough to slip in and pull it shut behind her, using the watchmen—if she couldn’t make them disappear, which she evidently could not—as noise camouflage. They seemed to be tramping downhill toward the harbor, so that after hearing them through the front door from the hall, she heard them last through the window panes of the storeroom:

“Your turn, mate.”

“I went right before you! It’s—it’s your sarding turn, fatso!”

“Neither of you took on a full turn! It’s not my turn yet!”

By the time she heard the muffled sound that she half-recognized from intonation as much as wording, of them resuming their cries, it was too faint for her to tell which of them had lost their argument.

Putting them out of her mind, she squared and shrugged her shoulders and took a deep, slow, calming breath.

Was she really going to do this?!

She couldn’t! She’d spent her whole life fighting to stay away from this. All her life, trouble had followed her. Was she really going to come looking for it tonight?

But no matter how much she thought about it—and she had kept thinking about it, a lot, from the moment her mother had first made it clear she expected Sindonie to come to Dublin—she couldn’t see a way around it.

She was so scared she couldn’t even sleep! And today had just made it worse, rubbing it even harder into her face that she would be at risk of exposure every day she lived in Dublin.

It scared her enough she almost—almost!—mustered the courage to defy Lady Parnell and Baron Wrathdown alike. She’d fantasized about doing so often enough, and for the longest time: with her mother, all her life; with the Baron, since she had first met him.

Could it really be any harder than staying here, to take her children and flee? Wexford, Chester, Bristol, London, Paris… anywhere, just far enough away to put her out of Lady Parnell’s and Baron Wrathdown’s reach. Was anywhere in Ireland (by which she meant, the Old English palatine lordships outside the Pale; the wild parts of the island would never even have crossed her mind) far enough from her—from either of them—to be safe? Was anywhere in England?

Maybe Scotland! She thought. Entirely independent of England and Ireland; but in much of which, English or its cousin Lowland Scots (which she was confident she could fathom) were spoken.

The desperate idea of leaving Char behind even crossed her mind, despite the guilt that immediately followed it. Without them, Char and Pen, the world would belong to her and Ollie. She couldn’t hope to marry, not a gentleman; no one even close to her rank. But she was still young enough to appeal to many men—most men—as a lover. And she was skilled, and willing. She could trust Oliver to stay out of trouble while she found them a new and magnificent home, perhaps some Scottish keep high in the mountains (but not the Gaelic Highlands—somewhere scenic, but civilized).

Or maybe a reiver Lord, on the border between England and Scotland. They were practically made for that, coming from the Pale, and Ollie would love it. Those borderlands had been contested so fiercely and so long, she had heard there weren’t just areas where both sovereigns claimed authority, but areas both sovereigns had forgotten about: liberties owing allegiance to no higher authority. If she could seduce the Lord of a Liberty who owed no one allegiance…. Now that was a near-perfect fantasy!

Only near-perfect, because while she could really imagine herself finding the courage, one day, to liberate herself from her tormentors…. She was afraid she could never overcome the part that was afraid to take Ollie away from the Pale. This was his world; and while he might have a fine and happy life on a reiver liberty surrounded by strangers, the life she owed him, better than an acceptable life, was here, where he was a squire, his grandmother was married to one Baron, his aunt was married to another Baron, and his mother…. Well, she had some connections at least, the connections he needed. If he could stay in the Pale, without his mother dragging him into infamy, then this is where he belonged; and where she wanted him to be. There was no way she would ever let her mother take possession of Ollie, or leave him behind to the impulsive shenanigans of the Baron Wrathdown when she was too far away to rescue him.

And anyway, she thought fondly, she could never bring herself to leave him behind and build her own life without him in it, or let him build his own life without her. Never.

Which brought her back, here, to this place, this situation, this pickle she was in. If she could… ah… avoid notoriety in Dublin (and the stake, a traitorous part of her mind added) she could almost get excited about the possibilities. Almost. It was crowded, and it stank. Two characteristics a wild child from the Pale would never feel reconciled to. And not free from either of her tormentors, but at least at a distance from them, able to live 90% of her own life for herself, instead of dancing to their tunes every minute of every day. And she was no longer at the center of their plans, she had been put out to pasture on the periphery. Let them concentrate on manipulating her sisters and Char’s brothers for a change. And the wealthy men… there were a lot of them in Dublin. She might have to go to Bristol or London itself to find more of them. Surely, she could find one rich man she could stand…. Char and Pen were supposed to be with Brother Griffin all afternoon, every afternoon but Sunday. Surely, she could find a man who found it convenient to socialize in the afternoons, allowing him to return to his wife and duties in the evenings?

All of which brought her back to this moment.

This threshold.

She was terrified to cross it, and with eminently good reason. For another second, she permitted fantasies of liberties on lost mountaintops between England and Scotland swirl back into her mind, even knowing they were pointless.

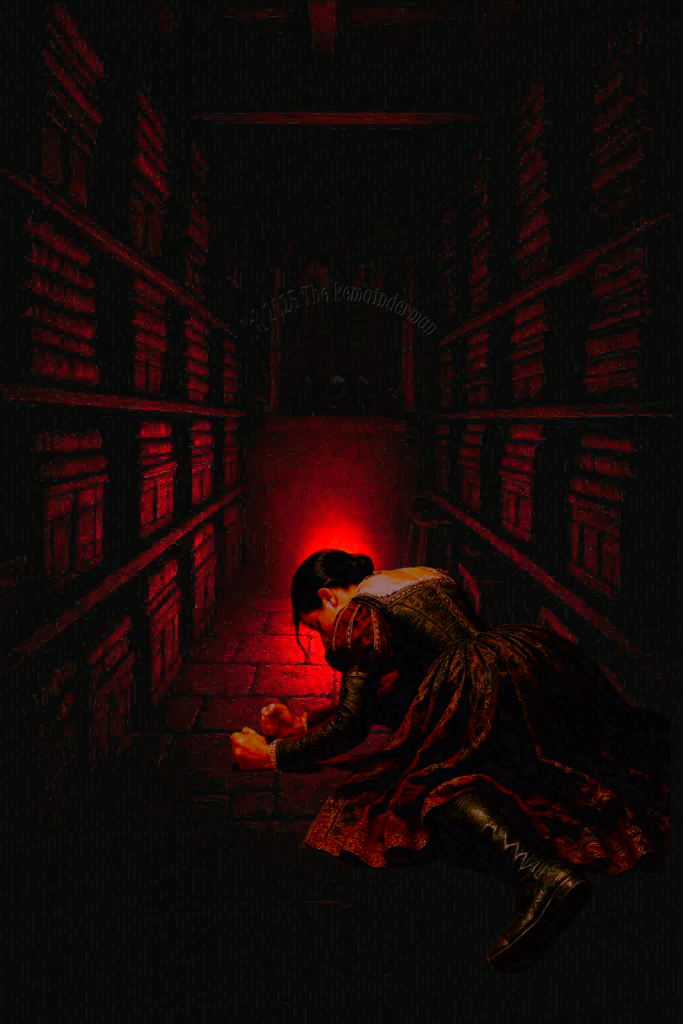

When she finally fell to her knees in the storeroom, using her fingers to summon her ink and to begin smearing her runes on the floor, it was more an act of surrender than of will. She wasn’t really acting deliberately towards a goal. Instead, she had exhausted herself, her own ability to resist, to fight reason and sense, so her body could do for her what it had to do.

She began whispering, the words pushing away her awareness of everything outside the room, even as the words began slipping into a cant, and then a chant, writhing and writing on the floor using her hands, sometimes together, and sometimes alternatively, to touch herself, evoking her medium, and then spreading it in precise and arcane patterns on the floor, invisible to the naked eye but blazing like beacons under that other sun.

Of all the nasty humors and pusses and fleshes and bones that filled the oft-disgusting human body, a few were useless; most were good only for a narrow, specific set of spells relating to them in particular; and only a very few—notably breath, mothers’ milk, blood, cum, spit, piss, and shite—were generally potent and efficacious media for magic, without effecting permanent damage or loss upon the body. The last three were too negative to ever cast on herself; they were for defiling others, her enemies and victims. The first three were too intimate and personal—breath binding lives, milk families, and blood oath-makers. Cum, a binder of friendship and convenience, could be intimate but without hard-core risks to life or sovereignty unless mixed with that of the opposite sex, a chemistry too powerful for mages to safely control.

Cultivating an open and liberal mind was a wise and valuable activity for anyone practicing magic, because to the extent one could experience lust for the object of one’s more practical and instrumental desires, cum was a cheap and safe medium for binding and supplication.

By the time She appeared, Sindonie was embarrassed by the intensity, intimacy, and inappropriateness of the thoughts and feelings she had worked herself up to feeling. Thoughts and feelings that by their nature, entreated Her to appear. If the demoness took her entreaties literally… she blanched, fearful and uncertain, suddenly thinking a little embarrassment wouldn’t be too bad…

It had started before she even realized it. As she pleaded and chanted, she despaired that she would succeed; what did she really know of such things? Being a victim of circumstances was different from trying to arrange them; perhaps they were the very antitheses of one another. But even as she felt hopeless, the room was darkening around her. For a moment, she wondered if she was losing consciousness, perhaps from her position kneeling on the floor, the intensity of her efforts, or her own success making herself delirious with arousal. But then she realized the room actually was getting darker; or rather, a thin dark mist was gathering near floor level; the mist expanding in a larger circle even as it became thicker, and then columnar in the middle of the circle like a stalagmite rising from the floor.

Next the mist started glowing, appearing as if it were heating on a stove, igniting from black to reddish-brown to an angry crimson-orange and finally a bright glowing cumulonimbus cloud of reddish-orange light, beginning to move and swirl as it thickened and brightened around the figure of a red demoness, more orc than human, more hided than skinned, heavy and thick with muscle and fat, horns decorated with engraved copper caps glinting in the flickering light; matching copper ribbons hanging from her horns and tail. She stood with her back to Sindonie, magnificent in her casual, unintended sexuality. She glistened and shone with sweat, moderated by soot; in gauntlets, apron, chaps, and boots that covered the front part of her body, the part facing fire and anvil as she crafted from iron and fire and smoke, from neck to floor; while leaving her backside scandalously bare, the leather straps holding her chaps and apron wrapped tightly around her skin and pressing into it like bonds, matching the decorations depending from her horns and tail; over only a thong and bra. Her tail flicked and curled and coiled from side to side behind her, a restless force in itself, separate from her conscious mind. Even being half-naked was not brazen enough to keep her truly cool in her hellish furnace, but it was less cloying than being mummified on both sides. As she became aware of the spell swirling around her and pulling on her, slowly bubbling up from the unconscious where Sindonie had begun her seduction, to the demoness’s subconscious and finally into her active mind, she set down the glowing, evil-looking little cage she had been holding to the fire in a pair of tongs; and peeled her monstrous obsidian-eyed leather mask off her head, flinging sweat from her soaked hair and the inside of the mask, as she looked around for her summoner.

Sindonie scrambled back and up to her feet as she finished her spell, to avoid touching the sparks and swirling flames that were somewhere between the fire of her forge and the burn of Sindonie’s spell, drawn to and slipping like a living thing through the cracks between that place and this one. She found herself hyperventilating with a sudden panic, shocked at what she had done, just as the beast’s eyes found hers. A second of silence stretched out awkwardly before Sindonie recovered her presence of mind enough to offer curtsy and courtesy: “Mighty and ingenious Dama Chava, thank you for receiving me; and welcome to our plane.”

Looking around her curiously, and stepping through the curtain to appear clearly in the storeroom bringing a storm of fiery, smoky, sweaty, perfumed air with her, Chava responded slowly: “Where are you—we? This? Exactly?”

“Your unholiness, we are in the city of Dublin, Ireland, in the orphanage of Our Ladies of Lesser Mercy Mary Magdalene and Salomé.” And then she added, uncertainly: “Er, on Earth, I mean.”

Turning her attention on Sindonie, she looked surprised. “I remember you, Sh-? Sh-something….”

“Sindonie Hyde, Dama Chava,” Sindonie curtsied lower.

Chava looked uncertain. “Sindonie?” She rolled the word around on her tongue, testing it. “Was that it? I certainly never thought to hear from you again,” Chava marveled. And then, her face softening: “And perhaps, I hoped—for your sake… well, when I heard your invocation…”

Sindonie reddened again. “I’m sorry, Dama, I—”

She laughed sharply. “Be sorry for yourself if you don’t want what you beg for. But I was only going to say, I was very surprised. Of all the livestock who’ve fed us, you were memorable for your disdain and resentment. I thought you, of anyone, would be done with us.”

Sindonie took one deep breath, then another, faster, stilling herself again and keeping her emotions at bay with great effort. Her eyes flickered with the sting of tears demanding to pour, but despite her tightness of voice she kept it level, after only one or two wavers: “I was supposed to be done—to be done with—the inferno. I prayed for it. But I’m not!” Traitorous tears forced themselves onto her eyes and cheeks, undercutting her dignity and mocking her determination to present a strong face to hell.

Chava, with just a hint of sympathy, waited a moment before prompting: “It can stick. The taint. The whiff of brimstone…. Tar is easier to set down and leave behind.”

Sindonie wanted nothing more than to bawl; but knowing well the myriad and extreme dangers of summoning, forced herself forward, trying to keep the interaction as short and professional as possible: “I think she knew—she didn’t warn me, but she arranged it so I would reach into the churchyard instead of entering it—I’m sure she knew!” Chava was just watching her, with more patience than she would have expected from any demon. She hurried forward before that patience could become exhausted, forcing it out as a rapid-fire whisper: “My mother made me come to Dublin to act as a lay sister with the Augustinians and they expect me to confess. But I can’t even enter sacred ground without my flesh catching fire! Let alone—I mean, I haven’t dared to think about sacraments since—” she dared to resume and maintain eye contact with pleading eyes.

Chava frowned in confusion, then burst into laughter again. “Oh dear. Do not tell me you’re seeking a demon’s help to attend church?!”

“You—you all—did this! I need you to undo it!” Sindonie burst out, before she could stop herself, her face red.

“Oh, no. No, you acted. And, it seems, you were judged. Not by me. We demons really aren’t ones to judge,” she smirked, before sympathy returned to her eyes, perhaps at SIndonie’s stricken look.

“I didn’t have a choice!”

“If there were consequences for you? Apparently you did.”

“That’s not fair!”

“Nothing is.” A twisted look crossed her face before passing. “I didn’t say you had an attractive choice.”

“But—but—you have to have some way to—to undo it—” She seemed to take Chava’s gentle shake of her head as a prompt to speak faster: “Take the taint off me, or—or at least hide it!”

Chava’s slowly shaking head was relentless. “We deceive humans. All the time, every day. But we can’t deceive the Holy Spirit. No one and nothing can. I can tell you—” suddenly she stopped, turning her head back over her shoulder, remembering or perhaps hearing something. Biting her lip, she shook her head again, decisively. “No. I’m sorry. I can’t. I can’t help you without making you pay.”

“What?” Sindonie whispered, paling.

“Mm… something. You must have had something you were planning to offer me, for my help?”

“Yes, but—I know what you need. Blessed things, the blessed metals.”

“Oh, yesss,” the demon hissed, nodding, very much interested. “That would be acceptable coin.”

“But—but if I can’t get onto sacred ground—”

“Hmm…” Chava rubbed her chin, making a thoughtful expression. “Perhaps I could give you the information in exchange for your bringing me blessed things if your quest succeeds.”

“We could—yes, I would promise—”

The demoness chewed her lip. “I would like to do it, but I have rules of my own. Give me a day and a night, and return to me again at this time tomorrow night, here.”

“Yes, Dama,” Sindonie curtsied again, looking trapped.

“It will be easier if you breach the portal. Any distance is enough, but I use 15 paces, to be sure.”

“‘Breach the–?’”

Chava squared her own shoulders and stepped forward, enjoying the cool shock of it as she crossed fully into the world, then gestured back over her shoulder toward the hole. “Walk through. 15 paces to be safe. Then come back. I’ll do the same on this side. Then this portal will—shit!” she hissed. “I can’t help you until we have a bargain. So…”. Then she shrugged. “Your choice. Do as I say, or don’t. Do as I do, or don’t. My sister Tirtzah is the only demoness you might encounter, simply tell her I commanded you to return after 15 paces, she’ll understand. But I’m going to… two, three…” she said aloud, so the human would understand she was counting off her own paces on the Earth.

She counted her remaining paces silently, hearing silence behind her for seven or eight paces; then, just as she paused at the door to the storage room, she heard the sound of Sindonie taking a deep breath and stepping through the portal behind her. Chava listened for a moment with her ear to the door before raising the latch and, with heightened alertness for any sound, counted her remaining paces as she strode out into the dark, cool hall, briefly lit with the red, watery light of hell. With a curious sweep of her eyes at every corner she could see, she made a small circle around the base of the spiral staircase, nodding with satisfaction. “Dub-lin.” As she finished her circuit, her eyes fell on the open door to the storage room, and right there beside it, on the other side of the half-open door, she met the eyes of two terrified, or possibly simply shocked, little long-haired children, seemingly paralyzed, their mouths and eyes competing for the title of “widest open.” After her circuit, she was left squarely between them and the rest of their world and they, without knowing it, were separating her from hers.

Frowning, she stepped quickly toward them, raising one finger to her lips and whispering “shh!” meaning to get close enough to cover their mouths before they started screaming or shouting.

They were so. Flabbergasted. She didn’t know whether to be impressed they maintained enough control over themselves to avoid peeing themselves, or amused that they were so shocked they couldn’t even muster a pee. But of course, her rapid approach triggered their deepest instincts.

None of them would ever know what the redheaded girl would have done on her own, because the blonde boy (judging by their attire), who was holding the redhead’s arm tightly, decided that instead of freezing or fighting, he was going to run, and either consciously or on instinct the girl followed the pull of his hand when he yelped: “Come on!”

Chava’s first thought was: Where are they going to go? And then a second later, almost as soon as they started moving, she figured it out: Oh, shit.

They bolted straight into the storage room. It wouldn’t have been much of a plan, as human plans go, if they’d known about the portal or where it led. But really, it was an even worse plan since, as far as they knew, the storage room was still the same dead-end it had been the first time they saw it. If it wasn’t for the yawning chasm to hell, they’d simply have trapped themselves in a narrow dead end where she could easily do whatever she wanted with them.

As it was, she wasn’t even sure if she saw them hesitate momentarily when their minds wrapped themselves around the idea there probably shouldn’t be a big, glowing, smoky red hole in the storage room; and they probably shouldn’t run into it. Or perhaps they were so focused thinking on her, they ran through the portal without even putting the pieces together at all.

Either way, they were through before Chava could catch up with them.

The sudden shock of the much-higher temperature on the other side, the tingling-grating feeling of passing through the membrane, or the sudden clarity of the other side after they were on it, brought them up short a few feet through the portal. Then, after a moment, they bolted to the right, out of Chava’s line of vision until she made it through the portal behind them.

She could immediately see why they’d cut to the right: Tirtzah was standing against the wall to the left among the racks of tools, lifting her own forge mask from her head, as sweaty and sooty and, well, bright scarlet, horned, and tailed, as Chava herself. She looked only slightly less surprised at all the sudden traffic, than the children had looked at the sight of Chava.

Chava registered that Sindonie was standing in the doorway past Tirtzah, looking up and out in awe at the landscape of hell, even as Chava was turning to the right to find exactly what she knew she must see: the two children, their hands raised in front of their eyes, standing several feet in front of the blazing flames of the augmented naphtha seep, their bodies assuring them in terms they could not misunderstand that they could not possibly squeeze past either side of the column of variegated flames filling the better part of the cavern. In fact, even if they could have gotten around the flame, they would still be trapped: The cavern dead-ended not far beyond the seep; and the hot air rushing in from the doorway Sindonie was standing in, rose from the seep with the flames through a narrow chimney to erupt from the rocky volcanic slope a few feet above them.

Surely, she thought, they wouldn’t attempt to force the passage, no matter how aggressively she came at them from behind; but out of an abundance of caution she approached them slowly, raising her hand to slow Tirtzah down as she caught up with Channah. Even Chava, as sweaty as she was, could smell her sister because, well, succubae smelled with the same force as scented candles or fresh cobbler, a spicy frankincense-myrrh-opium smell perfectly balanced against the brimstone scent of hell. They always smelled, not unpleasantly, but strongly. They were scented. Most female cattle didn’t react all that much to their scent; a fair portion of them even reacted with the instinctive hostility of a trapped cat when succubae approached them. But male oxen almost universally adored it, even the smell of succubae as sweaty and sooty as Chava and Tirtzah were from working in Chava’s blazing-hot forge. The pheromones in it were too powerful, and too complementary to male receptors regardless of the males’ natural proclivities, for any other reaction.

The children looked behind them to check on how close their pursuers were and looked at one another in dismay, right before the girl—followed in short order by the boy—dropped to her knees and—

“Noooo!”

“You can’t!” Chava cried, now racing as fast as she could with Tirtzah right behind her shouting: “Stop! Not here!”

But it was too late.

As if in slow motion before her, she saw the trapped children clasp their hands and start reciting the Lord’s Prayer: “Pater noster qui in caelis es sanctificetur nomen t—”

The next moment she and Tirtzah were on them. If it hadn’t been for the flames behind the children, they might have stopped them in time; but they couldn’t just dive and tackle them without all four of them getting badly burned by the fire in front of them. So they snatched up the two children, the blonde in Chava’s arms and the redhead in Tirtzah’s, and pulled them back away from the fire.

The children’s reactions left no doubt about their biological sex: As young and innocent as they were, as devoid of any adult sin as they could be, not even entirely gendered by the very gendered society they lived in, their flesh and that of the succubae recognized one another as deeply and perfectly as the flesh of females and incubi. After several hours’ heavy work hammering so close to the fire, Chava and Tirtzah were drenched; metaphorically lit up like fireships on a dark night. Even the males among the domesticated, pallid damned of hell, as thoroughly broken to the succubae as they were, couldn’t be used to assist the succubae here, under these conditions.

The blonde boy immediately started wavering in Chava’s arms, as if he were no longer sure he could stand up, his eyes drooping and a drowsy, dazed, passive expression coming over him. If this were sleepiness, he would have yawned continually.

Meanwhile, the redhead in Tirtzah’s arms reacted even more powerfully, seizing for a few brief seconds before passing out of consciousness completely.

If only that had been the end of it.

Succubae and incubi roaming the Earth couldn’t sense it at all. Those here who were busy, or far away, or weak probably didn’t notice anything.

But Chava’s Seep was directly beneath her Liege Lady’s castle, after which this hell was named. The site of the castle, and of the augmented seep, had both been chosen because they sat on top of, and close by, the very, infernal core of this place.

And the Queen of Sodom, the Hell of Lust, was neither weak, nor absent, nor particularly busy.

It was not alarm that brought her. She was too powerful here, and too rightly confident in her own power, to be alarmed, let alone scared.

But she was surprised, as surprised and delighted as any of the succubae or damned of hell who sensed it, to be rocked by the reverberations of prayers in hell. Their vibrations were so incompatible and opposed to those of hell they caused tremors; and the hope and faith they signaled were so rare in hell they were a local specialty valued like the finest caviar dusted in gold flakes: Exquisite. Exciting. A red flag promising a bull a smorgasbord of meaty delights to sate its blood lust.

Queen Channah, the sexiest, smartest, and most-powerful (and when she wanted to be, even the very fattest) of the succubae, appeared with a crack of thunder and an eager, amused, predatory look in her eyes. She was absolutely, breathtakingly gorgeous. Enough to make any woman, however thin, jealous; enough to raise the pulse and organ of any man, even the most-prejudiced in favor of pale twigs. Her eyes had a hypnotic, gravitational force to them so powerful one immediately recognized it, and had to resist the urge to dive into them. Only in retrospect, with benefit of that insight, did one recognize the same quality, much diluted, in the other two demonesses’ eyes, or its insidious action on men.

She wore an exquisite charcoal-gray dress and gleaming dark emerald snakeskin boots matching perfectly, symmetrically-braided leather thongs wound around her tail, which served to hold half a dozen clusters of copper, gold, and silver ribbons at equal distances along her tail starting just under the spade. Matching clusters hung from her black horns, which were at once longer and more elaborate than her servants’ without being unmanageable, and decorated to put them to shame, with exquisite inlays of copper, gold, and silver against the black horns, interrupted at the tips and five other equally-spaced points by metal caps and bands.

Chava and Tirtzah curtsied deeply, intoning: “Your Majesty!” Sindonie, her attention now fully on events inside the forge, looked even more overwhelmed than she had before. Wisely, she dropped to her knees and imitated her demon hostesses, all the while staring in shock, pain, and regret at the boys cradled in the demonesses’ arms.

“My Metalsmith and her… journeywoman,” Channah smiled, looking curiously back and forth between Sindonie, kneeling behind her; and the two young boys held in the arms of her vassals. Breathing deeply, she growled: “I had forgotten how sweetly you smell at your forge, my dirty red beasts. I am not quite sure which surprised me more: To hear someone praying in hell, or realizing it was coming from your seep! What, or should I say who, do we have here, and what are they doing here, praying?!”

“Your Majesty,” Chava answered, stammering nervously. “This woman summoned me to Earth to bargain, and while we were negotiating there, I spotted these two human boys hiding and they fled here and, when I trapped them—they just, started praying,” she offered with an apologetic shrug.

“On purpose?!” she asked hopefully; for any human who came to her hell on purpose, of its own free will, without being invited, became hers in every sense of the word, not mere physical custody.

“I’m sorry, Your Majesty, I don’t think they have any idea what’s going on… now.”

“They didn’t, Your Majesty,” Sindonie dared to interrupt. “They didn’t! Please, leave them alone! They’re just a couple of lost boys… desperate to stay as close to me as they could.”

The Queen turned on the frightened woman, a gaze cold enough to quench the seep if she set her mind to it, opened her mouth to speak, and then turned back to Chava, flicking her eyes briefly to the portal and back. “Where’s the aperture to?”

Chava gasped, realizing it was still open, and began raising her hand to close it.

“STOP!” Her Queen commanded, and she froze. “I asked you—where is it to?”

“Dub-lin, Your Majesty. On an island called ‘Ireland.’”

“Lillith and Cain, that’s nowhere. Still, I’ve never been summoned there from here before. If we’re adding an aperture under my palace to a plane I’ve never been, I should thread it before you close it. You have?”

“Yes, Your Majesty.”

“And Tirtzah–?”

“No—”

“Then come on, Tirtzah. You can drape your burden over Chava’s other shoulder or just bring him with you. But quickly, so we can close it.”

After they had both disappeared through the membrane, Tirtzah carrying Pen in twisted imitation of a mother carrying her child, leaving Chava and Sindonie staring at one another without moving, and presumably retraced Chava’s steps, they returned and Chava immediately closed it.

“Dublin stinks,” Tirtzah observed.

“Worse than Venice?” Channah asked.

“Not really. About the same.”

Sindonie was surprised to feel herself taking affront at the demons’ disparagement of Dublin. It wasn’t that they were wrong, just… they came from hell! It stank like brimstone here! Who were they to criticize the packed humanity of Dublin? Yet she wisely decided to refrain from weighing in.

“I think the strength of the stench is mainly a function of how hot they are.” Then, turning back to the astonished Sindonie, the Queen took up where she’d left off: “Where were we? Ah, yes. Cattle are to be seen, not heard. Which means you must be new.”

“We were only just bargaining, Your Majesty,” Chava explained, speaking quickly and swallowing every time she drew breath.

“Then why is she here?”

“I asked—I mean, I told her to come through! To thread an aperture.”

“You threaded an aperture here?! In the seep?! BENEATH MY CASTLE?!”

Chava was a reddish-pinkish-orange color, somewhere between salmon and coral red, by nature; much ruddier than her Queen or even Tirtzah. It would have been difficult for human eyes to decide whether she had managed to turn redder or paler; but her cheeks definitely changed tone. “YesYourMajesty!I’msorry!Wasthatbad?!Iwasn’t thinking—”

Queen Channah moved with impossible speed; or more precisely, did not move exactly, but suddenly changed where she was. No longer between Sindonie and her metal-workers, she now stood behind Sindonie with one hand holding a knot of her black hair tightly and the other pressing a long, gleaming dagger’s blade tight under her chin. “Why would you do that?” she asked with that same, terrifying, icy calm.

In that moment, it was hard to tell whether Sindonie or Chava was hyperventilating more.

“Iwantedtothinktobesureourbargainwouldpleaseyou!”

“You mean, you knew you were trying to be too nice!”

“Andshe’saspecialcaseYourMajesty!”

“Special? In what way?”

“ShewastheDragonKing’svessel!”

“Oh!” the Queen relaxed, intrigued, letting go of Sindonie and circling back in front of her. Sindonie just stared, mouth open slightly, as if she were afraid to make the smallest involuntary movement, even to close her mouth. As the Queen’s mood relented, the other three females all started slowly to relax, and breathe more regularly.

With a slow, wicked smile, the Queen recited: “insuper duxit uxorem Hiezabel filiam Ethbaal regis Sidoniorum.”

Sindonie blushed, hard, understanding the Biblical reference to Jezebel as an insult, but not quite certain how she’d earned it.

“Sindonie. That’s the name your father chose for you.”

“My—father?” she asked, startled. She knew she had one, of course; her mother just refused to speak of him.

But the Queen was pressing forward, not giving her time to try and make sense of the exchange: “You’re lucky I’m a practical succubus,” the Queen observed, as she returned her knife to a sheath on her emerald snakeskin shoulder harness. “Most demons stand on ceremony. And if I don’t find your interruptions useful, even I will make you regret them. I was told you had renounced your connections to us.”

“I’m trying, Majesty!” Sindonie assured her urgently.

“Apparently not very effectively,” Channah snorted. “Summoning… not the best way to avoid us?”

“I’m in danger—I’m always in danger, because of what I was made to do, but especially now that my mother made me move to an Augustinian orphanage in Dublin!” She cried, tears leaping back into her eyes. “I—I’m living in close proximity to churches, I’m surrounded by them, the damned town is filled with them! I’ve been there barely a day and already I’m expected to confess in Christ Church Cathedral!”

Channah laughed, not exactly nicely. “That does sound like a problem for you. But what do you want from my servant?”

“To remove the taint, restore me to the condition—”

“Restore you?” The Queen looked at Chava in confusion.

“Undo, or at least conceal, the taint that attached to me when I served my mother—”

“You served hell, darling! At the behest of your mother.”

“Oh no!”

“But—don’t you know?! Did your mother never tell you? That bitch,” Channah concluded, a tone of grudging admiration in her voice.

“What, Majesty?”

“Oh, you’ll have to pay if you want us to tell you. And these—children?”

“My son and I are—very close. Attuned to one another.”

“I would think so.” Another remark Sindonie could tell, she wasn’t fully understanding.

“He must have sensed I was up and about, and mentioned it to these two. And they were—foolish enough to follow after me. Anxious. They’ve both been through so much. Please, I’ll take them back—I don’t think they’ll remember or understand very much; I’ll persuade them this was all simply a nightmare!”

“They’re not yours? But you’re responsible for them in some way?”

“Yes… maybe—they’re sweet boys. I don’t want them to come to any harm!”

“They wouldn’t appear to be very ‘sweet,’” Tirtzah objected, frowning, lifting up the hem of the redhead’s dress just enough to show he’d been beaten. “And I can see and smell the blood from that one right through his pants. Punished before, misbehaving again now….”

“mmm, so that’s what I’m smelling!” Channah smiled, liking the idea, stepping closer to the child and seeing at least two streaks of reddish-brown blood where reopened wounds had stained his pants.

“They didn’t deserve that, Your Majesty!” Sindonie pleaded. “I was trying to protect them!”

“About as well as you’re trying to stay away from demonkind, I’d say,” the Queen commented cruelly. “What’s your assessment of them?” Channah looked back at Chava.

“My—assessment, Majesty?” Chava asked uncertainly.

Channah made a disgusted sound and stepped forward, setting one hand firmly on the top of the blonde boy’s skull, her pinkie and thumb nearly reaching his ears, her middle finger on his forehead; and set the other hand over his mouth and nose, with her middle and ring fingers in his slack mouth. “Their reaction to my servants is so strong, it suggests the kind of innocence one might expect in a young child. But let me see. Hmm…. He’s definitely traumatized, his nerves jangling all over the place. I’ll calm him to reach beneath…” she murmured, holding still. Then she shrugged and shook her head. “No. Nothing special. Nothing even particularly promising, except the trauma. He’s had more than one loss.”

“They both have, Majesty,” Sindonie dared, quailing as she offered it. “Please—”

“Hush! Yes, there’s enough to work with, here. He’s hurt and angry, and destabilized by his recent trauma. Traumas. He’s as innocent, and vulnerable, as any other,” she concluded. “But not one I’d bother to actively recruit. Plenty of more-troubled fish in the sea. Here,” Channah demonstrated to Chava, turning the boy’s head as she let it go and pressing it firmly into the wet, sticky, hot skin of her bare shoulder. “Keep him tight against you so he remains fully addled. I don’t want us doing anything to make their plight worse.” Any thought that might be intended as a kindness was dispelled in the next moment, when she explained: “They’re in plenty of trouble already, of their—and her—accord. If you carelessly make their plight worse than it otherwise might have been before bargaining, it can complicate your negotiations.”

Switching hands, but otherwise repeating exactly what she had done with the first boy, she took the head of the copperhead in her hands. “Ouch! Yes, this one’s pain is fresh, and extreme,” she observed. “His soul is as vulnerable and unstable right now as it’s likely ever been, or going to be again. So, a perfect time to strike.” Sindonie, herself stricken, felt a stab of anxiety on the child’s behalf. “But at bottom, this one’s even less promising. As open-minded and confused as most children, but with markedly little tarnish on his soul. This one is, or at least has always been, an altar-server.” The succubae laughed at that idea, finding it amusing. “No temptations. No grief or anger of note, under the suppurating open wounds from his recent experiences.”

“For your own sake, Chava,” the Queen continued, “I strongly recommend you learn to read them as a matter of course, before investing any time in one. It will allow you to steer away from the duds early. Here, sense yours, Chava. No, pay attention!” she insisted before Chava could even articulate a protest. “What do you sense? How big is the blackness?”

“He’s a good boy.”

“Yes, he is. And ergo, exactly what use is he to us?” She made a disgusted sound. “You want to feel festering when you reach into their brains… beetles crawling in dung… dread of the hours of darkness and silence… bitterness at others… wildfires straining to jump fences… a mortal spiritual sickness. Do you feel any of that here?”

“Maybe a little tickle of the dread and straining?”

“The moral equivalent of having a pulse. The lesion left behind by the sting of loss. He’s lost his mother and… something else—”

“His father just rejected him and banished him to the church because he was ashamed of him.”

“Chava, as entertaining as that story is, the darkness in this boy” (Pen) “is the absolute minimum required as proof of life, to be on this Earth instead of heaven; and yours isn’t that much better. If moving up the Catholic hierarchy had anything to do with moral virtue, this boy” (meaning Pen) would be a candidate for the next Pope. Yours, for a Bishop, or at the very least a Deacon. Don’t you feel that rhythmic hum, like a shining bell in his soul, ringing? You don’t want that! You want to feel the hatred bursting out of them, swarming over their doorways and mattresses.”

“I will try to do better, Your Majesty.”

“You should, if you don’t want to spend the next 20,000 years the way you’ve spent the last 5,000!” Behind his back, even as Sindonie stiffened in reaction to her timescale, the Queen looked down thoughtfully on him. “I wouldn’t call either of these boys an asset. But, thanks to her—” the Queen, using one hand to press the boy’s face down against Tirtzah’s sweaty shoulder to keep him insensate, pointed her other finger dramatically at Sindonie, cackling “—they’re here. And I’m certainly not one to look a gift-horse in the mouth.”

“NO! That’s not FAIR!” Sindonie protested, before remembering to choke back her words and be silent, mumbling: “Your Majesty.”

“If one bird in the hand is worth two in the bush, what are three birds in my dungeon worth?” And with a final, nasty look at the speechless Sindonie she turned back to Chava. “As uncharacteristic as it is for you, Chava, you’ve shown good instincts here, or at least adequate ones. So reel them in. Either they have to pay their own way—” Chava indicated the two boys by extending the pinkie and thumb of one hand toward them “Or she has to pay for them,” she pointed the index finger of her other hand at Sindonie. “But either way, three prices must be paid, each adequate consideration for the bargain: one to solve her problem, one to answer her question, and one to release these little miscreants. And since they’re too young to bind themselves, she’ll have to bind herself for them. Or I’ll have Cook boil them into a nice broth for my hassenpfeffer!” She threw her head back and cackled, enjoying Sindonie’s horror.

“But… how can I pay for them?” she whispered, afraid of the answer.

“I wouldn’t start there,” she suggested. “I don’t think even my cleverest, weakest succubus will be able to get you back into a church. Not for real. And most of the things you have to trade are going to be in those churches.” And when she saw none of the other ladies in the room had put it together yet, she pointed her thumb and pinkie back at the two boys. “Where they can get them for you.”

“No—” Sindonie shook her head. “No, I don’t think I can ask—”

Channah shrugged. “You, them; blessed things, hassenpfeffer stew. Six of one, half a dozen of the other to me. The important point is—you have three humans in hell, two of them uninvited, one of them pleading for favors. NO freebies, or I’ll exact the price from the two of you,” she threatened Chava and Tirtzah, persuasively enough to make the blood, or whatever passed for demon blood, drain from their faces. “Report to me when the bargain is struck,” she finished, and then disappeared with a flash and a crack.

Sindonie stepped back through the aperture first, taking Pen from Tirtzah the moment before she stepped through and meaning to carry him back to his bed box while Chava held Char in the storage room. But stepping through, as her vision cleared the dark room, she noticed a second before she stepped on him that her son was sleeping on the ground, right where the aperture was. Barely managing to step around him and stifle her urge to screech in surprise, she turned immediately and shook her head in an exaggerated manner though the portal, so Chava could make out what she was doing. Chava in turn nodded exaggerated understanding.

Oliver was already stirring. Desperate, she shifted Pen to carry in one hand, trying her best to crook her neck to hold his head with his face in the pungent scrap of cloth Tirtzah had given her, soaked with her sweat. She so did not want to think about where it had come from. Stooping awkwardly, she took Oliver’s hand as soon as he had risen to a sitting position, pulled him to his feet, and hurried him forward, just barely shoving the door to near-closed behind them to hide the source of the red light coming from the room before he came to his senses enough to look around.

“What was that?!” He asked in confusion. “Where did you—”

“Shh!” she cautioned him. “Speak quietly. What are you doing down here?”

“You went away,” he managed forlornly as she pushed him in front of her and followed him up the spiral staircase, using her newly-freed hand for leverage as she carried the child upstairs.

“What do you mean?”

“I felt you, you were agitated,” he whispered mournfully. “I guess I woke up Char, and told him I was worried about you.”

“Oh, honey…” she sympathized.

“And that you were coming downstairs. I—I told him to stay in bed but he woke Pen and took him to follow you. I could feel you, struggling with something, and I almost came down but then—then you disappeared! You were just gone! It was like you were in Wrathdown and I was in Skremen: I couldn’t sense you at all!”

“Oh, baby, I’m so sorry. You did the right thing. I wish Char and Pen had stayed too. I was—I was—”

“You did a spell?” Oliver guessed, cutting to the chase, and continuing when he saw her look of shock: “I’m not stupid, mom!” He hissed insistently as they reached the second floor. “And Mamo and my ainties aren’t as careful as you are.”

“None of your ainties have children. Yet.” Pausing before the door to the boys’ bedroom, she said: “we probably shouldn’t speak in there. The other children might hear us.” Kissing him on his forehead, she continued: “I can answer your questions, or at least I can try, when we’re alone in the daytime. I’m so so sorry I worried you, darling! But right now—”

“I know. I get it. Don’t worry—I’m a squire, mom!” He pointed out, straightening his shoulders proudly and shaking his head as if she were being ridiculous to worry about him.

“Of course you are,” she half-laughed and almost-cried. “Char and Pen got entangled in—in my spell,” she had to force herself to speak the word out loud to Ollie, marveling at the fact that it had suddenly become a good excuse to offer him, when for so long she had avoided any mention of it imagining it was the worst thing he could hear. “If they talk about it or ask you about it, tell them they must have been having bad dreams. It’s a lie, but it—it’s dangerous, for them and for me and even you—”

“I get it mom. Squire?” He reminded her.

“Okay,” she sobbed with a smile. “I love you, Ollie.”

“I love you, mom.” He practically rolled his eyes with his voice.

“Okay, you peek in and if none of the children are out of their boxes, beckon me to follow.”

The coast being clear, she followed Ollie back to their box, which he opened and she leaned through to lay Pen gently down, before remembering to take Tirtzah’s rag back, ignoring the skeptical look Ollie gave when he obviously smelled it. She wanted to tell him ‘not a word,’ but dared not say anything here, surrounded by the other children with only the imperfect doors of their boxes separating them from the hallway. So she put her finger to her lips.

Returning to the storage room as furtively as she could, she found Chava standing there, holding Char in darkness, having closed the aperture behind her again; and they transferred him to Sindonie, who re-used Tirtzah’s scrap as Char’s face pillow, before sneaking back up a second time and laying him in the box next to the slightly-stirring Pen and practically running to get out of the boys’ room before someone caught her. Returning to the storeroom again, the moment she pulled the door shut, Chava opened the aperture to reveal she was sitting on the floor with her back against one wall.

With an exhausted sigh, Sindonie sank down onto the stones opposite her, reminded by the succubus’s powerful scent to return Tirtzah’s fabric. She was going to be soo tired tomorrow! But she had to keep her head in the game and remain alert and cautious. She knew the next thing to happen would be negotiating; and from the unhappy, but deeply thoughtful, look on Chava’s face, she was afraid Chava intended to bargain hard so she could face her own master and explain their bargain without being afraid.

She had sat against one wall of files and boxes, facing Chava sitting against the other; keeping her knees together, between Chava’s relaxed, spread knees. She had meant to sit close, for silence; but as she sat down, she realized they were far too close to one another for comfort. The width of the hallway was sooo narrow, enough that Sindonie could not avoid touching Chava’s hips with her boots, or her smell in any way. Even being female, Sindonie felt the powerful attraction of Chava’s smell swirling in the hallway around them. It didn’t make her feel lustful, but… connected. Closely connected, the musks of her body almost trying to convince Sindonie they were sisters or best friends.

After a moment, Chava, determined but not a silvertongue by training or disposition, got right down to the point: “Do you have anything to offer, besides the Blessed Things?”

“I—I can spy for you?”

“Hmm. Maybe. But what would we want to know about Dublin? Or anywhere in Ireland, for that matter?”

“I—don’t know. What do you care about?” She volleyed back with yet another question, disconcerted by the idea her society, the entire landmass she lived on, could be so unimportant no one wanted to know anything about it.

“Blessed things. Cursed things.”

“What kind of ‘cursed things’?”

“Anything.”

“You want me to… curse things?”

“If you can develop a spell for that, sure; but it is a lot of work for very little reward, I’m afraid. I was thinking, perhaps you could find them. They’re much harder to locate than blessed things, because cursing is normally the sort of thing one keeps a secret. Usually, you have to gather a lot of information, keeping out a sharp eye for disasters or rumors linked to people or places or things to find them. It’s exhausting,” she added, with a grimace suggesting she was not unfamiliar with effort required.

“If I can get into churches, I can collect the Blessed Things you want. Dublin has more churches than trees, I can collect more Blessed Things than you could imagine—”

Chava shook her head. “I’ve racked my brain for options, but I simply can’t get you into a church. It’s not going to be possible. Ever—”

“How can that be?! There has to be a way!”

But the demoness was shaking her head. “Not even the priests can get you into a church. Ever. If you refused to enter church grounds I suspect you would be excommunicated as an unrepentant witch; or at some point, perhaps even be deemed a heretic and—“

“Be burned at the stake,” she whispered. “The church is supposed to forgive!”

“Not everyon—“ Chava choked herself off, seeing the confusion and rejection of that idea on Sindonie’s face. “That’s all—stop asking questions unless you’re ready to pay! Are you trying to get me in serious trouble?”

“No,” Sindonie fidgeted nervously. “No, I’m just—desperate.”

“The most I can do is offer you a glamour: an image of you, with your voice; that can hear and see. You would need to find a place to hide, near the church, and enter a trance to project and follow the glamour, animating it like a marionette. If you were caught and interrupted from the trance, the glamour would dissipate until you returned to your trance. The disappearance and reappearance of the glamour could cause speculation of witchcraft, of course; compounded if different people compared notes and learned you were in a trance outside the church while your glamour was observed and heard inside. Or, if someone tried to touch you inside the church, of course, they would discover it was a phantasm. If that happens, I’d recommend you have your phantasm flee from the church and hide long enough for you to awaken and act as if it had been you in the church.”

“Surely you can give it—heft? Or make people believe they’ve felt my solid form?”

“With a body, yes. Either someone recently-dead, but not yet putrified; or someone ensorcelled. Or a friend—” she turned and looked at Sindonie. “Those two little boys followed you to hell.”

“Not on purpose,” she laughed. “But no, I couldn’t do that—“

“Your son, then?”

“Never!” She hissed fiercely. “Leave him out of this! He’s never to be involved in any way!”

“I understand,” Chava nodded, not disapprovingly. “Anyone else?”

“No,” she shook her head, frustrated. “But I could pay someone…”

“Self-reliance is safer than alliance; and a loyal ally safer than a paid one.” After a long silence where Sindonie’s unhappy face reflected her own internal struggles, Chava suddenly asked: “Do you know the herald for Ireland?”

“The herald? Of arms?”

“Yes.”

“No. But I could try to get to know him. Probably not in time to save me…”

“Let’s review what you have to offer us so far: Your son.”

“NEVER!” Sindonie growled, her tone and force leaving no doubt how utterly she meant it.

“The two boys, but because they entered hell on their own, you have to buy them back from Channah first.”

“But they’re not in hell anymore!” SIndonie gasped in sudden realization, seizing on the idea as a way to avoid having to pay for them. “You let them go!”

“Their souls are their own. But their bodies belong in hell. And they know us now. To know us is to want us. I wouldn’t like to, but if you try to get cute with me, I’ll visit Char in his dreams and Tirtzah will visit the other one—Pen—and lure them right back through the portal. They both threaded it.”

“You wouldn’t!” Sindonie sputtered.

“You think not?” Chava gave her her most determined look. “My Mistress covered both their faces with her hands, and even put her fingers in their mouths. They have her scent and her taste. Do you think my Mistress wouldn’t cross the entire Earth to reach Ireland if that was what it took for her to reclaim them and punish you? Or, more likely, she would send one of her thousands of worldly minions to fetch them physically from Ireland after killing you, and all of your sisters—and your soon-to-be little niece or nephew—and most of all—“

“God’s body no!” Sindonie choked in horror. “Don’t even say it! I’ll pay! I’ll pay—“

Then, swallowing and visibly calming herself, Sindonie crawled up onto her knees and gazed into Chava’s eyes. Crawling closer to her, she hesitantly raised her hands, and finally dared to touch Chava’s hips, where they were bare, outside the coverage provided by her chaps. Chava giggled, looking pleased but hesitant, as Sindonie lightly ran her fingers along the larger woman’s skin. “Maybe I could—pay another way,” she whispered, leaning in to delicately press her lips against Chava’s.

“And I would like that very much,” Chava kissed her back, opening her mouth and tickling the tip of Sindonie’s tongue with her own. “I loved the way you summoned me. You were as ardent and elegant as Sappho herself.” If the unexpectedly-literate succubus could stop talking about lesbian poets for a moment, Sindonie insisted to herself, she would be able to imagine Chava was a man, a gentle man; even as she tried to persuade herself a demon’s gender was probably of no consequence, because they weren’t real, this couldn’t be real, none of it—Chava put her hands on Sindonie’s breasts. “Mmm…. I wish I were as devious as my sisters.” Then she pushed back on Sindonie, forcing her mouth and hands away from her. “I would enjoy taking advantage of you. But if you’re going to act like a whore, you need to think like one.”

“What?!” Sindonie gasped, taking offense even as her reason reminded her how stupid that was. She was acting the whore. So why should the label bother her? Or was she just offended at being rejected by someone she didn’t even really want to—

“My Mistress would say you don’t get any credit for sleeping with a succubus. If anything, you should pay us.”

“What?!”

“I mean, I’m really about the last succubus you should pick. Probably the last. But even I have done this a lot more often than you have.” And she demonstrated her point with a single finger that made Sindonie shudder, involuntarily and unexpectedly. “And you know, in a way, all of us—the succubae—are whores. Mercifully, built to enjoy our work. But with humans? I should bring you an incubus.”

“I’ve heard,” Sindonie whispered, still unable to fully process the reactions Chava’s finger—now, fingers—were eliciting from her. She swallowed and licked her lips. “I’ve heard you have everything an incubus has. When you want to.”

Chava chuckled. “And you’ve heard right. But as a succubus, I can’t take your soul, regardless of what organs I use.” Sindonie rocked back, as if Chava had thrown a bucket of cold water in her face. “So… freebie. But if we can reach an agreement on the important items, I’d have more… flexibility.”

Sindonie shrank back from the demoness’s fingernails, which she was waggling suggestively between them, wondering if she needed to stand up and move down the hall. But Chava just laughed and sat back, idly and provocatively playing with her own nipples beneath her apron as she regarded the woman across from her.

“I can give you the glamour for three Blessed Things.”

“Fine!” She agreed miserably.

“How are you going to fill your side of the bargain?”

“I’ll find a priest and persuade him to help me. I can come up with an excuse for one time.”

“As long as you only need the glamour once,” Chava shrugged.

“What do you mean?”

“One glamour for three Blessed Things. That was the deal, wasn’t it?”

“You’re as bad as the rest of them,” Sindonie hissed, in a tight whisper, her face whitening.

“I sooo wish you were right about that,” Chava looked down. “But I’m afraid it’s just that I’ve been in too much trouble for too long, to have any wiggle room. And then there’s the question of what you’ll pay for the boys.”

“Bitch,” she repeated, sobbing and shaking her head, with tears in her eyes. “I’m so fucked!”

Still refusing to look at her, Chava murmured down at the floor: “If you use the boys to bring you the Blessed Things, you’ll be fine, won’t you? Churches like trees in the forest, you said? And if they’re helping you, you’re trading their efforts for their freedom, while you trade your own for your glamours.”

Sindonie stared at her, just stared, with her eyebrows knotted and her lip trembling, until she dared to flick her eyes up to check on her, then quickly look back down. “You must be pleased with yourself. That’s what you wanted all along, wasn’t it?”

“Please don’t tell my Mistress I suggested it,” Chava whispered. “She’ll accept it, but I should have pushed for more.”

Sindonie hung her head in her hands, groaning, her rage giving way to the same melancholy that held Chava. She couldn’t really stay mad at her, the Queen herself having confirmed Chava’s story. But she felt guilty and dirty about bringing the children into this, especially after she’d intended not to. And it was compounded by the fury she felt at how unfair it was the demonesses knew a secret about her that even she didn’t know; and were trying to charge her to tell it to her! It was her secret! And she couldn’t—even—afford to learn it tonight! She might never be able to, not when the succubae were going to make her pay every time she had to step into a church.

They sat that way for what seemed a long time, but probably wasn’t at all, until Chava whispered: “If you still want to play…”

“I feel sick,” Sindonie choked, pushing herself to her feet. “And I need to sleep—I—I’m sorry.”

Chava nodded sadly as Sindonie practically fled for the stairs, barely taking the time to close the storage-room door behind her.

Literature Section “08-06 Everything Goes to Hell”—more material available at TheRemainderman.com—Part 6 of Chapter Eight, “The Wild, Wild West”—11,932 words—Accompanying Images: 4880-4889—Published 2026-02-18—©2026 The Remainderman. This is a work of fiction, not a book of suggestions. It’s filled with fantasies, stupid choices, evil, harm, danger, death, mythical creatures, idiots, and criminals. Don’t try, believe, or imitate them or any of it.