EXPLICIT VERSION AVAILABLE AT https://patreon.com/TheRemainderman

“Penny Batonnoir!” Sindonie chided her.

“I’m sorry Mistress!”

“Calm down and blame yourself, as I expect you to do with any feelings you have about how you’ve been treated the past week. What do you think, will you be neglectful when you’re with the Queen? Or will you girls help one another to make sure every inch of you is soft and appealing for Her Majesty when you bathe, before upsetting her?”

Unenthusiastically but sincerely, they promised not to be neglectful, turning away to rub the oil everywhere on themselves they could reach while frantically trying to stay covered.

“Good. And in back.”

“In back?” they asked, genuinely confused.

“Don’t even try to do it yourselves.” And when they tensed up in shock again, she reminded them: “Every part of you is in bounds for your Domina. You belong to her body and soul, outside and… inside. Such are the vows and magical bonds you have made with her. Prepare yourselves accordingly to honor her.” And then, as they reluctantly obeyed her, she continued: “No skimping. If I’m not satisfied with your work, I’ll do it myself, and believe me, the thought holds as little appeal for me as it does for you.” she shook her head and shrugged. “I have to tell you, the talk has been that you girls already should have learned this lesson. Did I hear wrong?”

They didn’t answer her in words, only by blushing, and on this occasion, she didn’t make them.

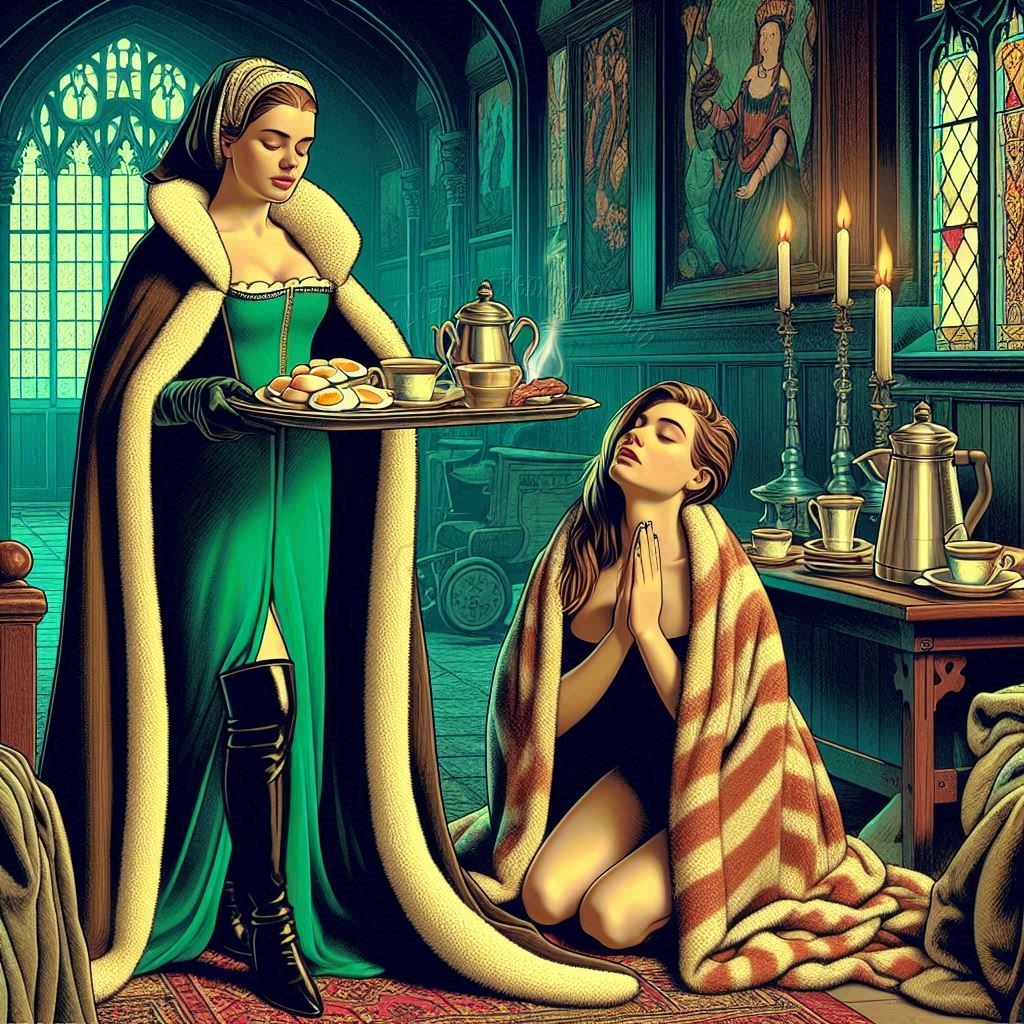

Hair and Makeup

“Good girls,” she finally allowed. “Back on the bench.” She hummed, as she usually did, while she brushed and pinned up their hair. “One last wedding gift for you. I want you to look pretty. When you’re with your Queen, help one another with hair and makeup. At least to check one another’s appearance before presenting yourself to her. Do you understand me, darlings?”

“Yes, Mistress Sindonie.”

“I hope so. If you present yourselves to the Queen with dry patches or loose hair or smeared makeup—” she shook her head, unable to even complete the thought, but communicating its gravity effectively as she lightly applied gloss to their lips—their fair complexions did not require anything bolder—and the faintest hint of color to their cheeks, before applying charcoal around their eyes. The amount she used was significantly heavier than the fashion, but it was the look the Queen preferred in her girls, matching her own appearance. Sindonie understood she had grown to prefer heavy black eyes during her centuries in Egypt, and had not been moved by more recent fashions to change her views.

Finally, judging her work done, she let out a relaxed breath, smiling at her girls in their mirrors. “You girls look lovely.” They blushed happily and thanked her as she ran a reassuring hand over their hair. “You’re ready. So here’s what’s going to happen.” She smiled mysteriously. “I’m going to walk out that door, and you girls are going to wait exactly one full minute. Then you’re going to leave your towels here,” she nodded and repeated herself before they could protest, “Yes, I know you like to be modest…”

“I want to be…” Penny interrupted imploringly, struggling to even complete the thought, as if she still didn’t understand.

“A girl!” Chas completed her thought for her, imploringly.

“I know sweeties. But this is a special occasion. Try to remember you are her girls, and she knows that—practically insists upon it—regardless of whether you’re dressed or not. You have nothing to be ashamed of. Your little cages are hardly bigger than a plump girl’s. Believe me, you’re going to like what’s coming, so be in your very best mood. The Queen has a very special and loving surprise for you, but she wants you to join her as you are. Do you understand? Will you obey?”

Put that way, of course they would.

Family

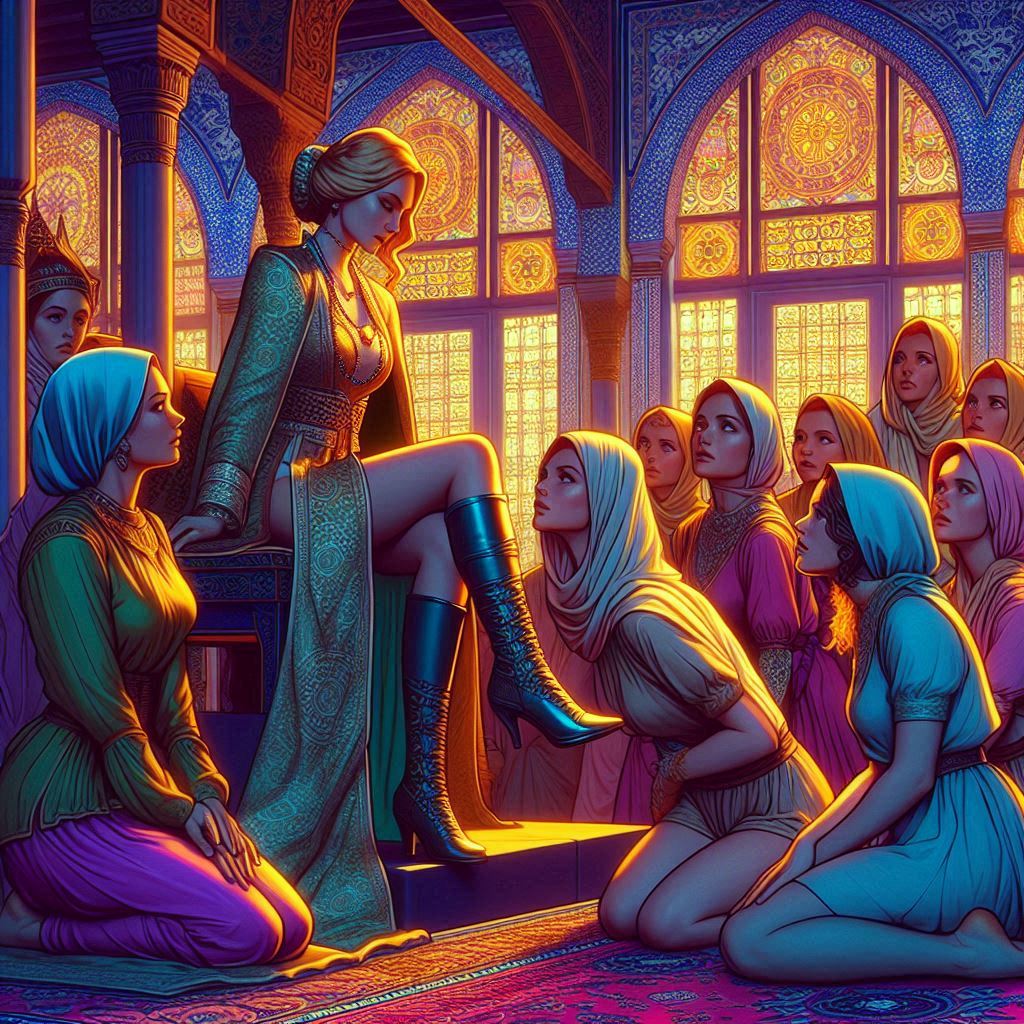

They emerged cautiously from the bathroom, with their hands held awkwardly in front of them, to find a pile of boxes wrapped in tissue paper on the table before Queen Channah, who was sitting on her lounge, so beautiful and perfectly-put-together the girls gasped involuntarily, their reactions clearly pleasing her as she gestured them to approach her.

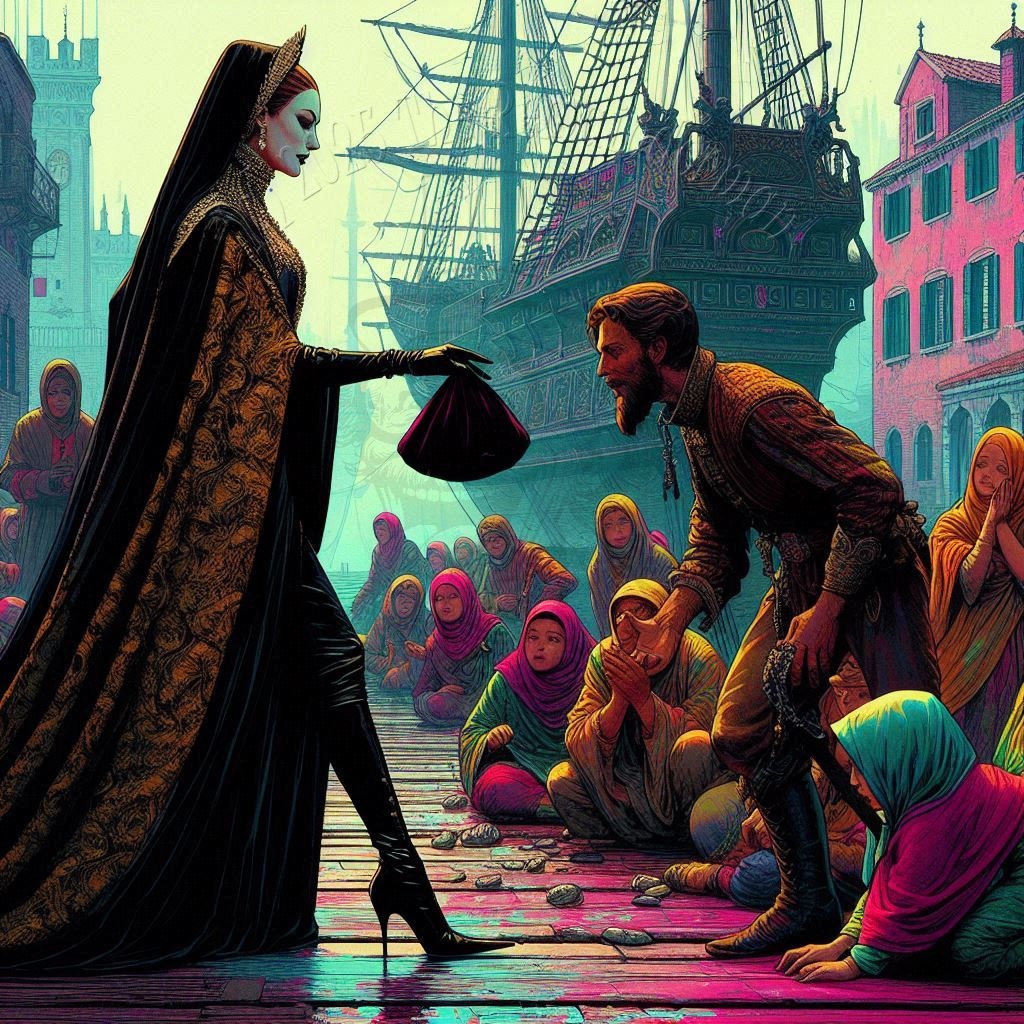

“Domina!” Penny gushed. “You look so beautiful!” And she did. She wore a perfectly-tailored scarlet brocade dress decorated with gold medlars and brilliantly shined black boots higher than her knees, as revealed by the slits in her dress extending as high as her hips. It had short sleeves and a fabric collar looser, but generally shaped like, the leather collars of the girls. Her hair was swept up in a single ponytail high on her head which was held not by a ring, but an exquisitely-detailed gold tube tastefully accented with rubies. And her long fingernails were painted black. In short, she was stunning, beyond exotic, and tempting as a siren. Her black eye-liner and -shadow matched the girls’, although her lips were redder than theirs. Her eyes danced with merriment and mischief and those red lips were twisted in her favorite expression, a sexy superior smirk.

“You do,” Chas echoed, her sincerity as obvious as Penny’s.

“Oh, you girls are so sweet,” she complimented them, then sniggered. “And so modest. After the games we’ve played,” enjoying watching both boys turn as red as cherries. “Oh, come here, girls,” she invited them, raising and holding out her arms toward them without moving, watching their nude forms, decorated only by the ensorcelled cages and collars she had locked them in, as they scurried over, neither one of them relaxing their modest posture even as they half-sat, half-flopped, on either side of her on the couch. They smiled shyly and wiggled themselves more tightly against her sides as she wrapped her arms around them, pulling them into herself. And finally, as she nudged them onto their sides pressed against her, their knees rising and crossing one another over her, they felt safe bringing out the hands they had been using for modesty. “Put those hands on my chest, right between my breasts. Go on, I want to see you holding hands for me.” And when they hesitated one more second: “Hands. Together. Now.”

Literature Section “06-47 Hella Honeymoon IV”—Part 47 of Chapter Six, “Le Saccage de la Sale Bête Rouge” (“Rampage of the Dirty Red Beast”)—Continued from 06-46[X]—Abridged 1042 words::Explicit 1052 words—Accompanying Images: 1545-1548. Published 2025-03-31—©2025 The Remainderman. This is a work of fiction, not a book of suggestions. It’s filled with fantasies, idiots, and criminals. Don’t believe them or imitate them.