CAUTION: Contains themes of institutional abuse and bullying some readers may find disturbing.

If this account is suspended, go to theremainderman.com or search for a new DA account with “Remainderman” in the title.

PREVIOUSLY: Two traumatized boys of 5 or 6 residing on the militarized Southern border of the Pale, Char and Pen, accompanied by Char’s governess Sindonie and her son Ollie, have just been given into the care of Sister/“Mother” Phillipa and the Augustinian nuns who operate Charitey Hous, the only orphanage in the Pale. With the not-quite tacit support of Sindonie (who also made an effort to appease Mother Phillipa’s wrath), the three newcomers defended themselves in an epic brawl that erupted soon after bedtime. Now everyone must face the consequences. NOW:

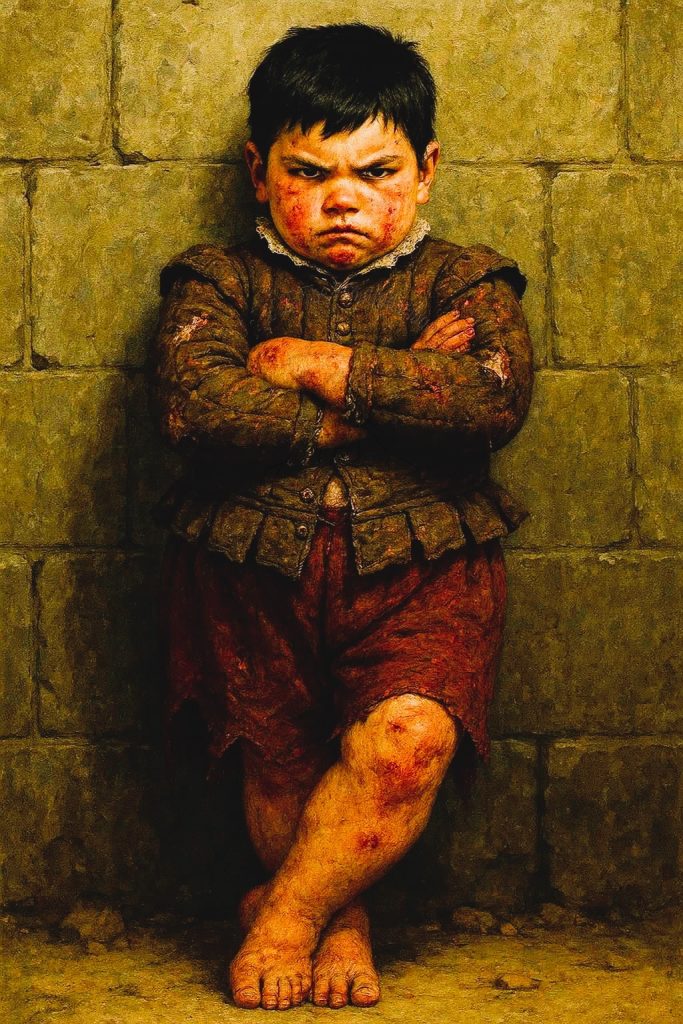

The atmosphere at Charite House was quiet and strained in the morning. Fighting was not unknown among the rough orphans there, not by any means; nor was the level of violence exhibited the previous evening. Indeed and fortunately, no one had required bandaging or setting. But the high social status of the three new boys and their governess, which instantly distinguished them from everybody else at the orphanage, or even in the neighborhood immediately around it, was a big part of it. Everybody knew—everywhere, but especially in Dublin—that commoners didn’t mingle with gentle people, let alone try to lock them in cupboards! The openness of it—erupting right in the middle of the orphanage, with virtually all of the children and their night wardens witnessing it—and the scale of it, pitting most of the older boys against three brand-new arrivals, were also, if lesser, distinctions.

Overall, there had been something notorious and shocking about it: The boys had crossed some kind of line by fighting; a line perhaps they weren’t even supposed to cross for friendship. A line the gentle children’s very presence here challenged. And before anybody at the orphanage, adult or child, had had much chance to get used to… however they were all supposed to get along together, the boys had transgressed whatever that line was or could have been with pranks that had escalated to brawling.

If the children could not fully conceptualize the problem, even the adults hadn’t had a chance to figure out how the newcomers should interact with the household before the children (subversively facilitated by Sindonie) had transgressed all possible boundaries. The fact nobody could tell what taboos had been violated, or how egregious they might have been, before they were smeared and blurred and broken by the transgression, just made it worse. If there could have been any doubt of what a violation the fight had been, the reactions of Mother Phillipa and the night wardens had confirmed it. The fact Mother Phillipa had reflected overnight on the boys’ punishment was generally viewed as particularly terrifying and solemnizing. The children knew Mother Phillipa didn’t punish children in anger—a near-revolutionary notion, but one that most of them viewed with the greatest respect and gratitude. But they couldn’t have known how much more complicated the older boys had made her problems.

Catching Sindonie in the hall, after the volunteers had arrived and gotten the process begun of feeding the children and readying them for class, Mother Phillipa took her arm—not hurtfully, but assertively enough to communicate that she had something to say and was going to say it, right then and there—and pulled her aside, leaning close enough so they wouldn’t be overheard.

“What?” Sindonie smirked, not entirely unhappily. She didn’t like being interfered with, but she did like Mother Phillipa, and understood her position required her to engage in some degree of interference. Before Sindonie had time to formulate any further reaction or plan, Phillipa spoke emphatically and seriously, impressing on Sindonie that this was a much bigger deal to Phillipa than to Sindonie: “I have prayed to God to help us more than He already does. To help these, his, children. I don’t know if you and your wards were sent to help us, but I fervently hope so.” Sindonie’s features softened with empathy for the sincere nun as she listened. It was hard not to be sympathetic to a woman who had so earnestly devoted herself to children, and seemed to heartfelt hopes of her own, rather than resentments, towards the privileged quartet that had been placed in the midst of her orphanage. “But I want you to stay, and if we can, I want us to try to make your children, and mine, better off with one another.” Sindonie nodded her agreement at that aspiration.

Mother Phillipa rolled her eyes, thinking and delaying at the same time, before she pressed ahead: “I liked you from the moment I met you. Certainly from the moment Brother Paul told me you were here to help, with at least the three new boys,” she admitted with a twinkle in her eyes, that faded into earnestness before she continued: “I don’t know what was in your heart last night. Or your head! If anything. Heaven knows, I’m trying to understand your three children and their place here, as fast as I can, and nothing is obvious about it. What?”

Sindonie had an odd look on her face. “My three boys. I would have said I had one boy. Even little Char—”

“He wasn’t your responsibility? I thought you were his governess?”

Sindonie now looked downright troubled. “I suppose I became that, these past few months. It was a role that… evolved. Oliver had just begun his apprenticeship, and I—my sister—our father was determined to make a match with Baron Wrathdown.” And sent us all there like a Byzantine beauty contest, to see what caught his fancy, she reflected bitterly. Her mother’s utter ruthlessness in, and focus on, building her husband’s domain and lineage were one of the reasons her parents got on so well.

“They saw how good you are with the children,” Mother Phillipa nodded.

“No!” SIndonie laughed, almost embarrassed. Try: Her mother had used her, at best, as an early lure. A sacrifice, a part of her—not quite her point of consciousness, but a part she knew to be trustworthy—corrected sourly. And: Nothing new there. Baron Skremen would have accepted a match with her, but certainly preferred it with his own blood. But as a used-up old widow of 25, she had been at best a long shot and at the most-cynically, a pawn ordered to do whatever it took to keep Baron Wrathdown engaged with them while Lady Parnell worked on him and could impress upon him the fertility and prestige of her brood. But all she said was: “Not that. As he was courting my sister, and as an experienced mother, caring for Char sort-of… devolved on me.”

“Well, you are,” Mother Phillipa insisted, her arm resting on Sindonie’s.

“What?” she asked, startled by the notion.

“You definitely don’t understand how to manage a group of children yet,” Mother Phillipa snickered, trying not to look as exasperated or amused as she was reflecting on the scene she had found last night, with Sindonie standing like a dazed cow watching while dozens of children lurched towards disorder around her. The image that had willed itself on Mother Phillipa was that of the Emperor Nero, fiddling while Rome burned down around him. “But I can see how the little lord regards you. And you he.”

Then he’s as much a fool as you, she thought guiltily. Uncomfortably. Very uncomfortably. What was Phillipa talking about? And she had no idea how cold and ruthless Lady Parnell was. Her instructions had been to undermine the boy with his father. Obviously, she wanted to protect and care for children. It was a woman’s nature—well, not Lady Parnell’s; but most women’s—to love and to cherish children. Of course asking a right woman, a feminine woman, to undermine the bond between a father and child, as all of them had been instructed to help persuade the Baron he needed more children, by a bloodline as robust as the Skremens’, was unnatural and painful. That was an essential part of the sacrifice demanded (not asked, for Lady Parnell had never asked anything other than as a form of grammar) of her.

When she reflected upon it, she could see she and the boy had bonded; but this was a recognition that had been forced upon her… she supposed, since yesterday. Not something she was ready for.

“And if you’re successful with your new boy—which I have every reason to believe you will be—” she offered encouragingly, seeing how troubled Sindonie looked, staring intently at ‘her’ three boys through the door of the breakfast room “The two of you will soon be close. Not as close as a true mother and child, but—for him—the closest connection he has in the world. Because he needs that, he will find it, with you.” Then Mother Phillipa giggled. “Goodness you look terrified!”

“What?” Sindonie asked, looking at her with surprised, feeling embarrassment at the idea.

“Don’t you feel it?” She reached up and put the back of her knuckles to Sindonie’s face, laughing. “Your cheeks are warm. Or scandalized.”

“I don’t know…” Sindonie protested, shaking her head and doubting Mother Phillipa’’s predictions, even if she lacked the confidence in her own judgment in this area to completely reject them.

“You’ll see. Reinforced because all of you—all of us—know you don’t belong here. They’d be a closer match to the Archbishop’s Palace than this house.”

“None of us is that kind of aristocracy,” Sindonie shook her head dismissively in a quick whisper. “But I admit, that thought may have crossed my mind, too. And I probably wish it had crossed the Archbishop’s mind, more strongly than even you do.” Still, she wouldn’t have dreamed of giving Baron Wrathdown the satisfaction of pleading for the Archbishop to consider it. Enticing him, might be a different matter; but not pleading. If she’d had more time, more than a few hours, an introduction under different circumstances than as the scarlet woman of Shanganagh and then in a crowded coach with a grieving child next to her, a brother next to the Archbishop, and three more people on the roof above them.

“And I’m a closer match to these children,” Mother Phillipa admitted without rancor, a simple statement of fact. “But maybe God has brought us together to accomplish a miracle. I’m not going to judge you, and I’m certainly not going to try and discipline you. I don’t even know who the Archbishop would support if I tried.” Sindonie had a scandalous thought, and with someone she knew better, in safer context, she might have joked about it, almost even flirted. But she just bit her lip here, and listened. “You and your boys will be attending Brother Griffin at Holy Trinity Within this morning?”

“Six days a week.”

Phillipa nodded, considering that. “And returning to us at noon?”

“Or close to.”

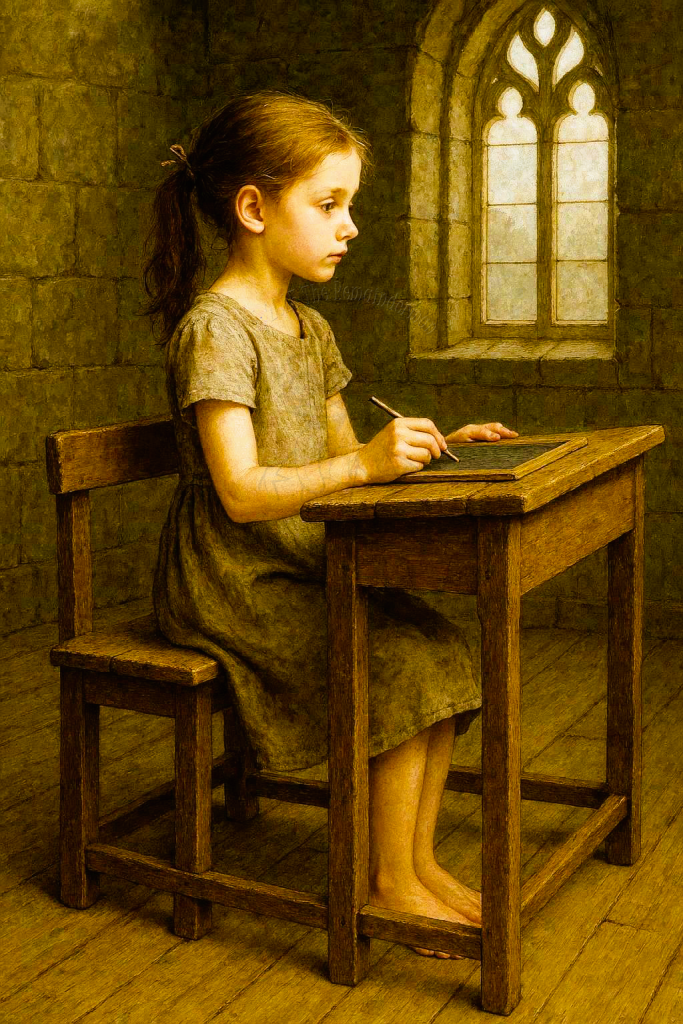

“And you plan to conduct lessons for your boys, while we continue to conduct lessons for ours?”

Sindonie shrugged, uncertain where Phillipa was going with this. “I’m not quite sure what the Archbishop has in mind. To tell you the truth, when I pressed him on the ride from Shanganagh, he… seemed to think you and I would be in the best position to iron out the details once we’d arrived.” Mother Phillipa didn’t look shocked by that. In fact, she gave SIndonie a knowing look, raising an eyebrow and curling her lip in a way that communicated amusement and disapproval at the same time. Smirking back at her, Sindonie elaborated: “He spoke as though you and your sisters didn’t teach the curriculum expected for noble and gentle children. But of course, he also thought they should have their own room…” both women giggled at that, preposterous under the mean circumstances of the orphanage. “… without making provision for it.”

And Sindonie might have pursued more aggressively, the possibility of being accommodated separately by the Archbishop in his liberty of San Sepulcher if Brother Paul hadn’t apologized to her early in their carriage ride that the orphanage was on palatinate land under civil jurisdiction of the Corpo, rather than on cross land under the jurisdiction of the church.

“So,” she continued, “I think it’s fair to say, he’s more concerned than the Baron seems to be, about whether the boys are treated as they’re accustomed.” Her face hardened. “But these boys were raised on the Pale. They understand every boy needs to be able to hold his own as best he can. And we all understand why the boys were sent here.” Sindonie felt her face heat a little, wondering if the nun wasn’t asking herself why she had been sent here; but she was determined not to open the door to anything about that.

“I ask because,” Mother Phillipa explained, “For the sake of my house, every child in my care must be treated with the same hand, without favoritism. And when something—like this happens, they must all be disciplined alike, in proportion to their age and offense. We must decide, between the two of us, right this very moment, and before the children take the task away from us again: whether we want these children to be kept and treated separately, or kept and treated alike.”

“And we cannot possibly have it either way completely,” Sindonie exchanged a knowing look with Phillipa, who nodded. “Because we only have the single, six-room building, a single kitchen, and a single bedroom.”

“But the children need separate educations because they must be made ready for the very different paths before them,” Sindonie finished the thought.

“If they’re to live together, but study apart,” Phillipa began.

“Then they should be punished together.”

“And evenly.”

“But you and your staff should discipline the orphans.” And neither woman felt it necessary to voice that Sindonie discipline her young men. They were, after all, of a class only Sindonie was a member of. And it was the rare, unusual circumstance, and only with the clearest permission and authorization by noble adults, where an adult commoner would dare to discipline a noble child.

“Normally, for new children, I give them a quick introduction to the rules of the orphanage, so they know what to expect. Perhaps—perhaps I could share with them, and with you, the rules that govern the other children here; and you could explain to them—to us,” Mother Phillipa gestured toward the house generally “what they will be expected to do?” And after Sindonie nodded, she practically rushed into her next topic, as if it were particularly uncomfortable: “Your dress and manner with Brother Paul and with me—” Mother Phillipa began.

Sindonie raised a curious eyebrow. “Yes?”

“It’s just—we do have religious sisters here who may wear habits to show they are part of our community when they volunteer, but dresses when they return to their homes. I have only seen you in dresses. Am I correct you’re not a… religious sister, are you?”

Sindonie laughed sharply, then covered her mouth immediately, embarrassed. “I’m sorry sister—er, mother. Goodness no!”

Nodding, Mother Phillipa dropped the bombshell: “Thank you, sister.” By which she meant only, a fellow Christian woman. Looking and sounding a little bit relieved, she concluded: “Then if you are a problem for the church at all, you are the Archbishop’s problem.” Sindonie didn’t look happy about that statement, but it went without saying she had to be placed under the authority of an appropriate man. “By coincidence, or I suspect much grander design, he’s taking confession at noon Sunday at Christ Church Cathedral. You might want to ask him if he might appoint Brother Paul or another cleric would have the time to supervise you adequately.” And seeing Sindonie bristle, started apologizing nervously. “I just mean—I would want some guidance, and there are few enough men of noble rank in the Augustinians here in Dublin. The Archbishop, Brother Paul, and the Dean of St. Patrick are probably the only ones.”

But bristling was the weakest of Sindonie’s emotions at that moment, though Mother Phillipa could hardly have hoped to understand the younger woman’s thinking. (In fact, Sindonie and her mother would have done almost anything to prevent any of those around them from even guessing at what they might be.). But even as it was, Sindonie gasped and turned slightly pinkish, sounding scalded. “Confession? I—”

“It’s quite rare!” Mother Phillipa cautioned, lest this be something Sindonie would find disappointing.

“It’s been less than a year since my last confession—” Sindonie blustered. More precisely, a fib; suggesting her hesitance came from the fact she hardly had any business wasting the Archbishop’s time with her own situation. “I—”

“He usually starts after Sext. And with a pause for None, he continues until Vespers, seeing as many people as he can. The line is always quite long.” And leaning forward to squeeze Sindonie’s arm, she urged her: “Find someone to help guide you, especially at first.

The nuns and lay sisters arriving in the morning to help could tell something was wrong before the night matrons even had a private moment to fill them in. The orphanage was like a living thing, with a routine and pulse of its own the boys and their governess quickly came to appreciate. Morning was the second-busiest time; the busiest, when the largest number of women helped out, was evening. Night, when the children were supposed to stay in their sleeping-boxes, saw the smallest staff, sometimes as few as two women but usually three; and now, with Sindonie’s arrival, maybe one more. The children ate their two meals a day in shifts because there simply wasn’t enough space for them to eat at once. The children who already had day-placements left first thing in the morning to be fed by their masters; and bathed last in the evening; partly because their masters both were responsible for feeding them, and wanted the benefit of as much work as they could get out of them, but also because the daylight activities of Charite Hous would have been difficult enough to conduct with half the children; the staff needed to get as many of them as they could, physically out from underfoot, to accommodate the teaching and chores of the remaining children. of the way as Classes, chores, and other activities filled the kitchen, the classroom, the hallway, or even the empty floor spaces of the bedrooms—including the matrons’ rooms—or when the weather was bearable, the tiny privy yard out back the orphanage shared with the workhouse, the Cock and Bull pub, and the building the sisters referred to in hushed tones as the “kenells,” even though there weren’t any dogs in sight.

Like a pair of lungs, expanding and contracting in a hand-me-down bodice that may never have fit at all, but had quite definitely been outgrown now, the orphanage was an organic thing requiring more room at day than at night; and always straining at its boundaries. Simple physics by itself created pressure adding to the sisters’ own sense of mission, to find placements for children as soon as they could, anywhere that they could.

This morning, the three apprentices allowed to leave before breakfast had been scurried out early so they could inform the masters of the five boys being—Cutter Henry, Luckless Martin,

“They keep a lock on the back door and of course, we’re not allowed to answer either door.” Clemence—the girl who had complimented Char last night, and invited him to the girls’ room before the sisters squelched that idea—was explaining to the boys. A drying, wilting bouquet comprised of a dandelion, a She giggled. “Unless it’s the Pope, or maybe the Archbishop. You can only go outside with supervision. But if you can’t get an apprenticeship, you move across the courtyard to the workhouse,”, whispering the last and making it sound like a sentence to jail.

Clemence was kneeling on the bench right next to Char and half-covering him. Even if he’d been inclined to complain, which (being a sociable enough child, he wasn’t), there would have been little enough to complain of. The children were all piled on top of one another like cordwood in the orphanage, day and night, with few opportunities to be alone. Char was too young to have realized already, that boys from the half-deserted borderlands were probably going to feel claustrophobic sometimes in the crowded city. For now, it was still a novelty. And besides, like the rest of them, he had plenty of real problems to unsettle him. Noble or no, troubles were one of the great leveling facts in an orphanage. No one came here because they preferred it to a good life they might have enjoyed elsewhere. But whatever it was about the workhouse, Clemence seemed to have the impression it might be worse. She whispered: “Then you work for Sister Phillipa.”

Char blinked, but before he could ask, Pen beat him to it: “She runs the workhouse, too?”

Clemence frowned a little bit, like Pen’s question was a distraction or interference. She hadn’t had much interest in Pen last night, when he looked like a wild thing. Now that he was bathed and dressed exactly like the other boys in the orphanage who weren’t lucky enough to have serviceable hand-me-down clothes, he was wearing one of the simple gray robes the Augustinians made for charity. Hardly likely to provoke positive attention. Clemence answered to Char, who obviously wanted to know, too. “You mean Mother Phillipa. To us. Everyone—well, almost everyone—” she looked uncomfortable. “Calls her Mother Phillipa. The real Sister Phillipa runs Our Ladies’ Workhouse.”

“She’s a nun, too?”

“No. They call her a ‘religious sister,’ although—” she lowered her voice; and if she could have done so without making even herself uncomfortable, presumably she would have leaned even closer in to the boys to answer: “Elizabeth overheard some of the nuns saying she wasn’t very religious or sisterly.”

“That’s funny,” Pen opined.

“She’s not funny. She’s… the opposite. I don’t know what she is, exactly, but she dresses like a nun. Only… she still doesn’t look like a nun.”

“What does that mean?” Char asked, curiously, but Clemence just shrugged uncertainly.

“Nobody likes that place,” another girl, across the table from them, murmured.

“It’s on Preston’s Lane,” an older girl said sharply, emphasizing like that was an important fact. “Not the alley. It’s fine.”

“That’s not what I heard,” Clemence frowned.

“What do you and Elizabeth know?” The third girl, whose name, as they boys would later learn, was Blythe, demanded, rising from her place, apparently deciding she was done with breakfast. “Have you ever even been outside of the House?”

“No,” Clemence shook her head, as did the younger girl across the table. All of them reckoned the privy as part of the house.

“Calm down,” said

“Of course not. You’re babies. Both of you should keep your mouths shut instead of—spreading rumors—”

Suddenly Blythe swallowed nervously and stood up, setting her knife on her plate so she could pick up both her plate and her glass. Ducking her head, she scurried away, her meal incomplete.

The boys looked at one another. “What was that about?” Char asked.

“You don’t have to worry about it, do you?” she stroked Char’s hair. “You won’t have to apprentice anywhere. Anyway, they find placements for most of the boys.”

While Char and Clemence were talking, a boy who had been standing against the wall holding his plate with one hand and eating with his knife hand, spotted Blythe’s vacated seat and swooped toward it until he noticed the big, mean-looking girl with dark hair and pox scars already approaching it. At the mere sight of her, even before she gave him a dangerous look, the boy swallowed, intimidated, and backed up until he had returned to his place by the wall. It was she who took Blythe’s place, simultaneously glaring at and bumping Pen with her hip, squinching him up against the boy on his other side, who opened his mouth to complain, looked up, saw the girl, and decided to focus on his own breakfast. Char and Pen swallowed nervously, understanding what they had just seen. Char, across the table from Pen, was sitting between Ollie and Clemence. Pen was now squished so tightly on his side, he didn’t even have room to bring his elbow back to his side. Instead, he had to hold his knife arm awkwardly in front of him between bites.

The girl gave him a nasty smile as she leaned over with her knife and took Pen’s sweet from his plate, setting it beside her own, daring Pen to do anything about it, as she returned her attention to her fish. “You look uncomfortable,” she smirked. And when he didn’t say anything, she leaned against him, chewing right in his face, her head blocking him from his own food. “Are you?”

“Yes,” he admitted, startled.

“Good,” she laughed, turning back to her own plate. Both of them had heard giggling from the other children around them, and Pen shrank down a little bit more in his seat. “I’m thinking what your name should be. I want to come up with a good one!” she chortled.

“My name is Pen—”

“That’s probably going to be part of it,” she demurred. “It’s so stupid already, it’s going to take me awhile. But when I can think of anything stupider, I’ll let you know.”

“What do y—” she rounded on him quickly, putting him off guard again, and pushed her dirty forefinger against his lips. Pen could smell a bit of the sweet on her finger, along with something earthier and older.

“You’ll address me as Miss Rose. Say it.”

“Miss Rose,” he said without even pausing to consider it, and she laughed again, turning her attention across the table. Her eyes fell on Char’s knife, silver where hers—and everybody else’s, except Ollie’s—was brass or bronze or iron, and decorated with floral flourishes, where everyone else’s (except Ollie’s) was simply functional.

Everybody ate off small, square, simple tin plates, similar to one another but not quite matching in shapes and lack-of-decoration. Bread, greens, roots, fish, and even the porridge was made thick enough it could be served on the plates and eaten with fingers or knives. One of the neighborhood ladies—the secular volunteers—had said you could use the porridge as mortar. The glassware was the opposite: where the plates were similar, the glasses were a riotous collection of every shape, color, and description to be seen in Dublin, clearly donated or perhaps found on the streets or scavenged from the trash piles of Dublin. Any vessel would serve well enough; water seemed to be the only drink at the orphanage, except for the very youngest children who Clemence said might get a little cow’s or goat’s milk if they were particularly sickly. And every child had their own knife, usually dull and as close to what the King’s chefs might recognize as spoons or undersized spatulas, as they were to the knives used by the butchers on Skinner’s Row.

Char had made the mistake of asking about meat, feeling uncomfortable when he realized none of them had ever had meat. He wasn’t going to be stupid enough to ask about fruit, or cakes, or honey, or wine and ale. He set his jaw, determined to show Miss Sindonie—and his wicked father—that he could make do just fine without meat or fruit or ale or cakes or anything else his father and brothers thought he’d miss. He wouldn’t!

Her eyes bulged with astonishment and a moment later, envious desire bloomed in her face as she noticed something else different about Char’s and Ollie’s knives. She gasped: “You have a real edge on your knife!” And she rose up from her seat to reach across the table and take Char’s knife right out of his hand, throwing hers on his plate in its place.

Char stared at her in astonishment, at least doing better than Pen at resisting her by saying: “Hey! Give that back!” and trying to take hold of it again. She rapped the handle of his own knife, hard, against his knuckles, batting his hand away and sneering as Char withdrew and cradled his hand saying “Ow!”

The next instant, her sneer was knocked from its perch by surprise, as Ollie effortlessly plucked Char’s knife from her hand, set it in front of Char, picked up her knife from his plate, and tossed it back at her. By chance, when her knife struck her plate, it knocked loose a fleck of porridge that spun in an arc through the air, striking her forehead with absolutely no effect but surprise. By pure instinct, she pulled her head back as her eyes registered the flash of flying, moist grain, wiping it away in the next instant. She was staring at Ollie in shock; then her face turned a little bit pink as Ollie, with a quick smile, returned his attention to his own meal, observing: “That’s Char’s knife. Too good for the likes of you.”

None of them noticed Sindonie, watching Rose interact with “her” boys from across the room; going from sorrow over Pen’s collapse to dismay over Char’s, and pride at her son’s quick and instinctive action to protect his friend. But, heaven above, she would have her hands full keeping her boys safe here, let alone help them to thrive. The border was a hard place to grow up, but so was this place, the human garbage dump of the Pale; only mad and crippled children, who no human had the means or understanding to help, and a few children so broken by their brutal infancies they posed a real threat of death or serious physical harm to other children, were turned away from this place. Not to mention the fact everything about them marked them as outsiders. To these children, they may have been more exotic than the natives. And on top of all that, they were both naturally small and gentle children in what seemed to her to be a collection of the burliest and hardiest children she had ever seen. But she supposed these children had to be stronger than average, simply to survive their infancies, in their terrible world. Lucky to be from the Pale? What a notion. How on Earth was she going to do her job—the job of her heart, not her assignment—with them?

Staring blankly at Ollie, Rose’s mouth worked in astonishment and indignation, without any sounds coming out, until she suddenly rounded on Clemence and spat: “You’re just as stupid as Barmy Blythe, Clumsy Clemence!” She grabbed the much-younger girl’s hair and yanked mercilessly on it, eliciting two screeches from her, one when she felt the hairs trying to pop out of her skull, the second when her stomach hit the side of the table.

“I’m sorry, Miss Rose, I forgot!” she apologized profusely. “I’m sorry!”

“That’s not even what I mean, you driveller!” she insisted, letting go of the smaller girl as she noticed Mother Phillipa turning more in their direction as part of whatever she was doing. “Although you should give her the proper respect.” The Southern boys were completely confused. They were confident Rose was not suggesting Clemence ought to be treated with respect, but had no idea what she was suggesting. “I meant Sister Phillipa is always interested in boys who were as cute as your girlfriend there.” And she laughed at Char, giving him a venomous look.

“You’re mean!” Clemence cried in dismay, as true as it was ineffective.

“She’s going to want him the moment she sets eyes on him!”

“Why?” Clemence and Char asked simultaneously, both of them worried now.

Rose just laughed meanly. Again. And with a look askance at Ollie, seemed pleased he didn’t know what she was talking about, either. “You’re a child, Clemence,“ she said, putting as much cruelty into her words as she could. “Both of you are children! But you’ll find out soon enou—”

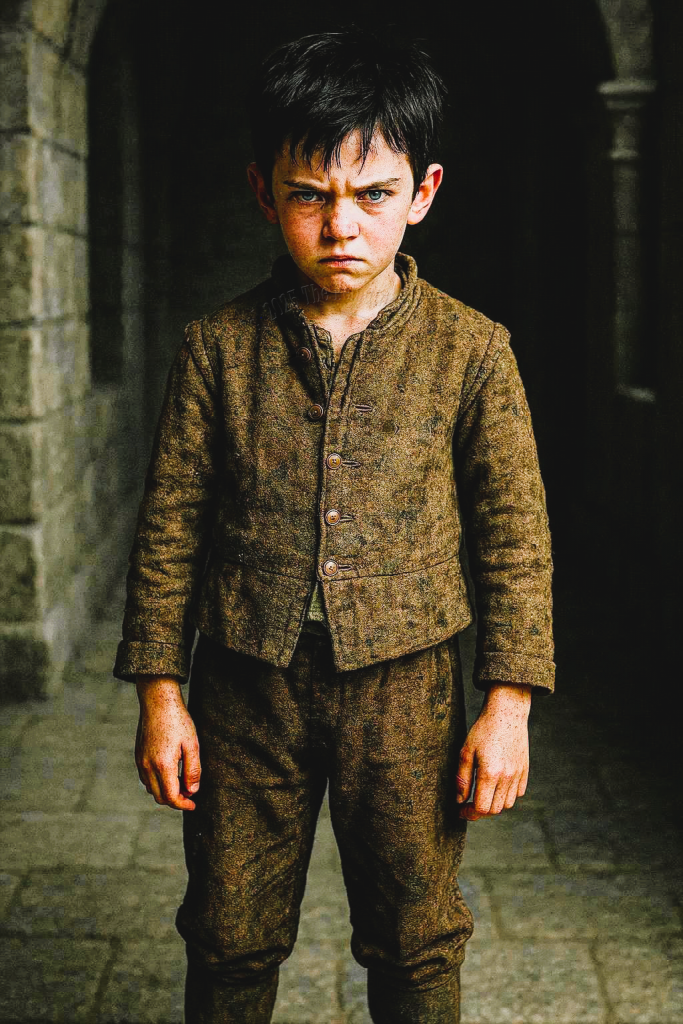

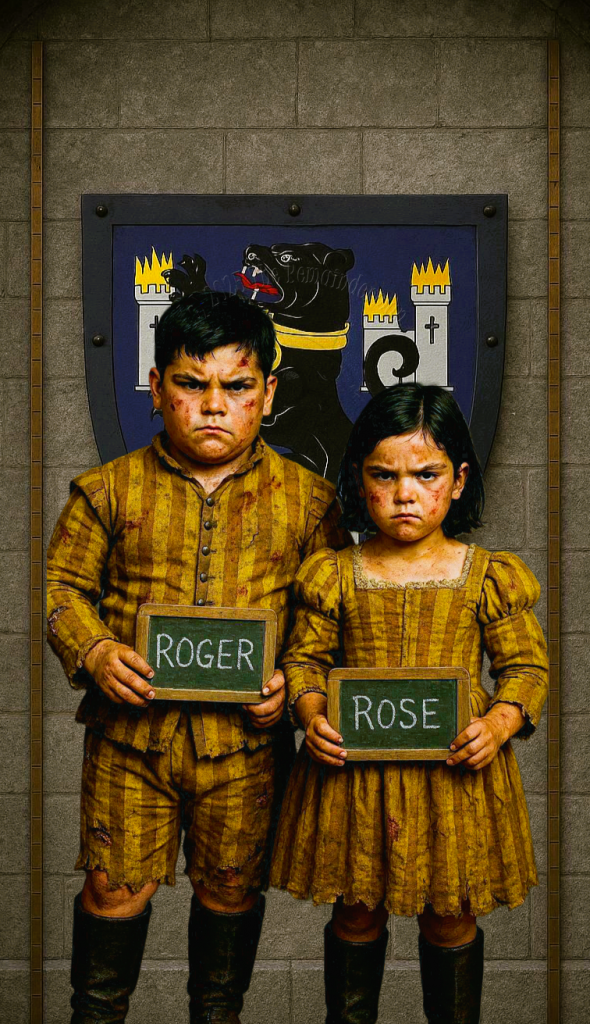

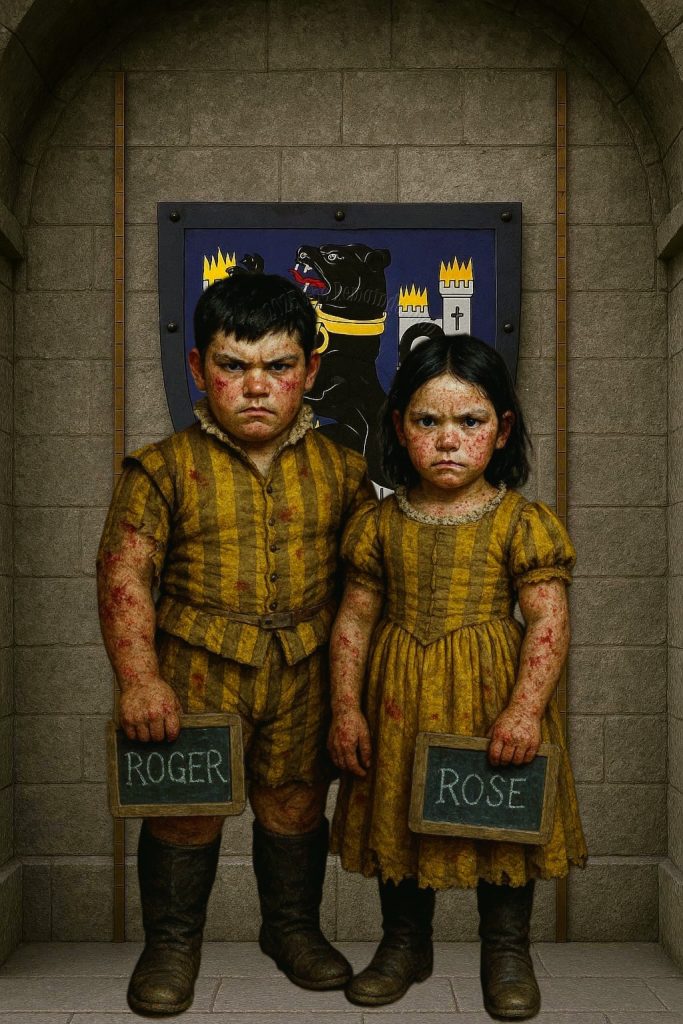

Her eye was drawn toward the door as something—a reaction—went rippling through the room, and the rest of them followed her gaze. A boy, larger and at least seeming older than the rest of them, had just walked in, heavyset with black hair and cold piercing eyes intense enough to register before the fact half his face was black and blue with a fierce, fresh bruise. Something tight in his posture and movements hinted at pain rigidly controlled. He projected an unmistakable confidence… and an equally-unmistakable threat. His tight, glowering, surly expression matched his tight posture and the tension in him. His resemblance to Rose was unmistakable; they practically could have been twins, in body and personality, if he weren’t a couple of years older than she.

Like Cutter, the other older boys who had been placed in the community already, and Ollie, he wore pants, marking him as a young man. Ollie’s breaching ceremony—the occasion when a boy, usually around seven, was deemed a boy or young man instead of a child, and given the right to wear pants—had occurred as part of a larger squiring ceremony here in Dublin, at St. Patrick’s Cathedral; where Baron Skremen, somewhat incestuously, accepted him along with Char’s older brother Arthur, as squires; in exchange for Baron Wrathdown accepting the boys of three of Skremen’s knights as his own squires.

Oliver and Char guessed who the new boy was—must be—before anyone identified him.

Some kind of emotion Pen couldn’t quite identify, swept across Rose’s face before it disappeared below the surface again, leaving the hard intimidating and inscrutable expression that usually reigned there as it did on her brother’s face. She rose to her feet, leaving her plate where it was, either because she had forgotten about it, or—more likely—because she felt certain no one would take either her food or her seat away from her.

Hurrying to her brother, she reached tentatively towards his bruise, murmuring to him with a concerned expression on her face. He batted her hand away, speaking sharply, but without physically separating from her. Returning to their table, Rose ordered Pen: “Move!” shoving him backwards off his bench so he landed on his back on the stone floor. A wave of laughter swept the room as Pen embarrassedly scrambled to his feet and Roger took his seat, Rose settling down beside him with their backs to Pen.

“Hey!” Pen protested. Busy whispering to one another, neither of them even bothered to look back over their shoulder towards him, emphasizing his impotence and lack of importance.

Mercifully or not, before Pen could really decide about how to react to what had just happened, Mother Phillipa spotted Roger, her mouth forming into an “O” for a moment before she asked “Roger! Are you all right?” Mother Phillipa strode toward him, ignoring his attempt to brush her off by signaling he didn’t need any help. “What happened?”

She was asking what everyone wanted to know. Even if none of the children had any problem guessing what had happened. Maybe Mother Phillipa already knew as well. “It’s nothing, Sister. Just Hard Henry being…” Roger considered, then shrugged: “Hard Henry.” The room was crowded, but not that big; and the children had fallen silent when Mother Phillipa had called out to Roger from across the room. Their conversation was now the center of attention, and even Sindonie, who had reappeared, was listening.

“Are you hurt?” she asked, gently setting her hand on his shoulder on the side away from the bruise.

“Of course not!” he scoffed, shaking his head, offended at the suggestion he might be so weak.

“Well—” she seemed to want to get through to him, which she had obviously not, not in all the years she had cared for him. Finally she asked: “Has Hard Henry given you time off this morning?” That didn’t sound like anything Hard henry was known for doing.

Roger laughed. “When Bernard told us about the new fopdoodles—” he glanced at Char and Ollie, not having any difficulty identifying the three new children; or by Char’s and Ollie’s clothing, their social standing. If that was what he was referencing with the slang term. “Hard Henry said I could come watch the big whipping if I would ask if you’re putting on a grammar course for them.”

That didn’t sound like Hard Henry either. Mother Phillipa blinked, meeting Sindonie’s surprised eyes for a second. “What’s his interest in grammar school?”

“He said—he asked, Sister,” Roger rephrased, perhaps deciding Hard Henry might be in a better mood if Roger could report back success, “whether he could send me and Cutter. And Rose. To learn Latin and counting.” The last part was asked defensively and too casually, Roger obviously quite uncomfortable with some part of the request, or the underlying idea.

“Why–?” Mother Phillipa laughed out loud for a second, looking embarrassed the laughter had escaped her and raising her hand to her mouth as if to physically help her quiet down. Three less-likely candidates for advanced instruction—especially with the ‘fopdoodles’—she could not imagine.

“He wants us to help him read his books.”

“Hard Henry has books?!” It was all she could do not to fall over laughing at the idea.

“On surgery,” Roger explained. And with a gesture toward his sister, he added: “And brewing.”

“Absolutely not!”

Roger’s face closed off as he asked: “Is there a reason I should give him?”

“How about three of them? First, may God bless all three of you, you’re probably the worst-behaved and most-rebellious students I can recall at Charite Hous! You’re not going to learn anything! You’re just going to keep our three new students from learning what they’re very much expected to learn! Second, I should fear for the future of Dublin if anybody could teach you and Rose to read and write—and, oh Lord, do sums! A set of skills more likely to be abused to corrupt the entire community…” she shook her head, hardly able to complete the thought out loud, as Roger and Rose exchanged a suspicious look, like Mother Phillipa was having them on. “And third, Cutter and Rose have each attacked them already, independently, unable to keep their hands off them for a single quarter-hour after gaining access to them, even while your baleful influence was temporarily banished to Hard Henry’s!”

Rose and Roger looked at one another again and Rose blurted: “So much the better for us!”

“I’ll tell Hard Henry, Sister,” Roger added.

After a final frown down at them, Mother Phillipa looked out over the room and clapped her hands above her head for attention, and getting it immediately. Everybody had been waiting for her to address the elephant in the room since they woke up; and before she had clapped twice, you could have heard a pin drop anywhere in the orphanage.

“Cutter. Fulke. Big Ed, Lucky Martin, and Luckless Martin!” With uncanny precision and awareness of the room, she managed to meet each of their eyes in the exact moment she called on them, amplifying their dread of what was about to come and rocking them back on their heels. “For your inexcusable conduct last night—unwelcoming to newcomers, cruel to younger children, and possibly even trapping them, and for daring to trespass against young gentle men, I sentence you each to 35—” the room gasped and gawped at the sentence—“stripes! Follow me!”

Swallowing, trying to digest the number of blows Mother Phillipa had sentenced each boy to and also suddenly nervous by publicly disciplining her boys to prove they were treated the same as the other children, Sindonie cleared her throat and announced: “Ollie, Char, and Pen! For your inexcusable conduct last night—outsmarting and whooping on these five boys, and exercising your privileges and abilities as their betters to punish them out of anger instead of careful consideration, I sentence you each to 35 stripes! Follow me!” The room’s verdict was much less ambivalent with respect to the new boys’ sentence, as it had been with respect to the other five. Although the five boys who attacked them were not popular, they were in a sense the “home” team until the boys got to know Char and his companions; and so the other children had felt torn between a sense of loyalty and their personal dislikes. Whereas with the new boys, they were simply pleased.

For their part, Roger and Rose grinned at one another before turning their derision on all eight of the sentenced boys. Mother Phillipa marched out of the room and up the spiral steps to the third floor, followed by “her” five boys; then Sindonie and her three boys. The other children all yielded to Roger and Rose, who led the spectators while a couple of the sisters tried to persuade children to join them in the classroom, or remain here in the kitchen, to start their regular classes.

But for most of the children, the lure of the spectacle to come was too much. Half-motivated by uncharitable thoughts and desires, for most of them, at least, there was equally an element of their own dread, feeling the same sickening drop in their stomachs as those to be disciplined. They were driven as much by their inability to look away, as they were by any actual, affirmative desire.

“Mother Phillipa?” Sindonie asked. “I wonder if you might take my son Oliver and let me have one of yours?”

“Of course,” Mother Phillipa nodded, assuming she understood, but not completely certain about it.

“I don’t want anyone thinking I’m going easy on my son. And—you’ll see—he’s tough. Please, let me take the toughest of yours in return.”

Mother Phillipa opened her mouth to respond, then decided the occasion was too serious for her to display levity. Certainly not before the proceedings had commenced. So she accepted it at face-value. For now. Several of the older children grinned, looking forward all the more to hearing Ollie start bawling.

She also had misgivings about whether it would be fair to let Sindonie take her most-difficult student, Big Ed. At 35 blows, he should cry. They should all cry. Any reasonably sensitive child would. If Sindonie didn’t make her wards cry, the other students would never take her seriously. She fervently hoped she would pass this test; kicking herself for not discussing this issue specifically when they spoke. She had to trust Sindonie was sensible and tough enough to do what needed doing; it would be unfair to presume otherwise, based on anything Phillipa could see. Lord knew, the frontier woman had her flaws; but weakness and carelessness hadn’t appeared among them so far.

“Where do you prefer to do this?” Sindonie asked.

Phillipa responded: “I find my prayer bench is best. It is, after all, made for kneeling and prostrating.”

Sindonie whistled, impressed. She had seen it last night, and thought it odd. But she’d been dealing with a lot last night; and she hadn’t connected it at all with today’s punishment.

“And I think it will be plenty big enough for us to share, with the boys bending over it from opposite sides. If you have your own switch?”

Sindonie laughed. “I do,” she answered, walking slowly and meeting the eyes of all eight of the boys while going to her trunk, bending open and opening it theatrically, and then returning. “I am a mother and a governess, after all!” she explained, as if anyone had tried to argue differently. Then she flashed them all a smile. “Of course I carry the tools of my trade.”

Mother Phillipa’s eyes widened. “Is that… birch?!”

“Yes, Mother Phillipa,” she answered shyly.

“So is mine! This one has been at Charite Hous, and in the possession of the head matron here, for many years.”

“I took this from my mother. Who took it from my grandmother before her.”

Mother Phillipa seemed to want to ask a question, then thought better of it. “If, perhaps, you could stand…. There?”

“Of course, Mother Phillipa!” she smirked. “Big Ed?” Sindonie asked the biggest of the boys quavering in line.

“Yes, Mistress!” He answered formally, if with a sparkle of hope in his eye, pleased to have gone from a known-bad quality—Mother Phillipa—to an unknown one. He hoped to find out she was too weak to punish him properly. As a presumed troublemaker, Sindonie doubted he was usually so polite or correct, if he felt he could avoid it. But she’d been on the wrong end of the whip often enough in her own life, she certainly understood the urge to be particularly placatory and appeasing to your punisher in the period leading up to the sentence.

“Soooo…. Respectful!” she cooed, drawing a laugh from the children gathered behind and around Roger and Rose near the door to the hall. Even most of the younger children laughed, whether it was simply because they were following the leads of their elders, they were simply nervous, or they actually understood the joke, she wasn’t sure. But Sindonie shared a conspiratorial grin with her confirming she had definitely been amused. “Drop your breeches and pull your shirt up, then lie right here.” She patted the bench, smiling with deceptive sweetness to Big Ed before striding over to her trunk, positioned at the base of her canopy bed.

They wasted no time. The moment Big Ed and Luckless Martin (“at least one of you has a fitting nickname this morning”) were in position, they began. Luckless Martin howled immediately; although, as Sindonie would have guessed, he had a reputation as a weakling. A mesne bully: A cur, who lashed out at viciously at smaller and weaker children, but ran or cowered and heeled in turn the moment he was confronted by anyone stronger, or even challenging. Not like Roger and Rose, both laughing at him from their prime spots near the doorway inside the room, who Sindonie suspected were a much tougher nut to crack.

Big Ed was somewhere in the middle between them; but with ruthless determination she gauged her violence to the level required to break his resistance, getting him to howl by the fifth blow and weep by the fifteenth. She kept one eye on Mother Phillipa as bellwether for the adults, and the other on Roger, occupying the same role with respect to the children. By her twentieth stroke, she saw an ugly grin spreading over both siblings’ faces when they looked at Big Ed’s wretched face that told her they were well-satisfied with what she had done to him; and were not at all resentful or even worried that he might get off easy by drawing her as his disciplinarian. And on Phillipa’s face, by the high twenties, she saw genuine worry, confirming for her what Roger and Rose had already communicated: That she hit harder than Mother Phillipa.

“Sindonie, perhaps—” she asked tentatively.

Sindonie laughed, feeling triumphant, her severity now officially recognized. “He’ll be fine.” She paused for a second to test his cheeks. “Definitely warm, but hardly enough blood to notice. I suppose I’m used to Oliver. You’ll see.”

Phillipa looked at her in something between wonder, uncertainty, and horror. It wasn’t that Sindonie was bigger or stronger than the nun—quite entirely the opposite; in a fight (the thought of which she couldn’t even imagine with a woman as centered and reasonable as Phillipa), she hated to think what the tall, strong, heavyset nun could have done to her. Rather, it was Sindonie’s will and determination to impose her will and accomplish her goals that drove her hand forward with such sharp force. And, perhaps, the gnawing fear; always present in her life, but heightened from the moment her mother had ordered her to Dublin. Sard she could hardly even hold it in her head, the fear so strong and slippery it was harder to catch than a fish with bare hands. It was only when she saw something like conspiracy or hope—perhaps desire—in Roger’s eyes that she checked herself. She didn’t care for cruelty, she told herself. It offended her. Even if she was capable of it.

She punished Pen next. For the first time since they’d met, he was less than cooperative. He balked at following her command to pull up his dress and bend over the prayer bench, freezing for a moment and then shaking his head. Her eyes widening in genuine surprise, Sindonie repeated her command: “Skirt up, butt down right there!”

“But—but Mistress—”

“LAST CHANCE!” she barked at him, startling him over the bench before she had to wrestle him down. Didn’t he understand how bad it looked, as if he were too scared—or too good—to take his punishment the same as the other boys? She could see the muscles in his bottom, legs, even his arms, bunching at a level of intensity she didn’t quite understand. After being hit? Many people would clench that way. But beforehand? That was an unusual degree of stress and fear, or… something like it, she couldn’t put her finger on. Anxiety? Uncertainty about what was coming? What, as if he hadn’t been beaten a dozen or a hundred times before.

After stunned stillness and silence in the second after her first blow, his only sound a ragged gasp for breath, the boy had burst out blubbering and pleading and kicking so hard, trying to get to his feet, she gasped in surprise herself. “You little cringeling!” she burst out before realizing what a mistake that had been, catching him by the hair, pushing him back down across the bench, and stepping on his lower back with all her weight to hold him in position while she dispassionately delivered 34 more strokes to him, trying to keep her mind a blank, to ignore the laughter of the meanest children, who had just heard her diminish the boy with her outburst; the shocked look from Phillipa; and most of all the pure frenzy of her victim. The only two things that saved him from becoming irretrievably marked as the runt of the orphanage were the extremity and the hostility of his reaction.

The boy went mad. With all her efforts, she was barely able to keep him in place and maintain her balance well enough to give a solid base for her continuing blows. By the time she let him up, after having resolutely delivered 35 strikes to match the blows to Big Ed, his face was as red as his bottom with rage, humiliation, and frustration. Tears streaked down his face, snot dripped from his nose, and spit drooled from his mouth, each of them a volume of fluid greater than the few wisps of blood on his backside from where the tip or edge of the switch had torn his skin. The second she let him up, he came after her, eyes wide and wild, hands clenched somewhere between fists and claws.

His assault left her with exactly three options: getting upset—perhaps what most women would have done—reacting with the cold, calm, terrifying composure of an ice queen (her mother’s specialty, and something Sindonie could master when she wanted to), or taking it in stride and minimizing it. She immediately judged the last course to be the best outcome for him, spinning him around and hugging him from behind, using her arms to pin his down by his sides and shushing him while he continued to buck and kick and hurl nearly-incoherent verbal like a crazy man. By a combination of luck, dexterity, skill, and alertness, she managed to avoid bumping heads with him, being seriously clawed by him, or hit in her own turn. Phillipa, pausing in her own administration of discipline to Fulke, walked over to the cage in the corner of the room and unlatched it, holding it open in case she needed it.

Sindonie didn’t judge it necessary, but she did think it would be better for Pen’s reputation that he be caged, so she wrestled him over to the cage; and with Mother Phillipa and the help of another sister, they pushed him into the cage and locked him in before he could calm down. Once he was securely locked in, she whispered: “Keep acting crazy for a few more minutes. The longer you can keep it up, the better off you’ll be.” Despite his genuinely deranged state, she could see the confusion and suspicion in his face when he registered her words, and she could see him trying to make emotional and logical sense of them.

But that was all she could do for him. Having kept her cool throughout, she was the very picture of composure by the time she rocked back from her knees to her feet, stood, and turned around to face the room. She raked her eyes coolly over those of the children, seeing the respect and awe she had hoped to inspire, leaving no doubt about her own, or her boys’, credentials. And their glances at the cage were… acceptable. Dominated far more by fear than excitement. Whether it was Pen’s lunacy, the unexpected fight, or the sheer and obvious misery of the cage, too small for any adult, deliberately designed and built to be too small for a child to stand, sit, or lie down in, let alone stretch his or her limbs. Pen’s discomfort was obvious, his head forced down between his knees, dragging his head back and forth over the bars as if trying to force them to expand.

Being deliberately nonchalant and disinterested, she smiled a wintry smile at the children, watching them shiver, and strolled back to her place, where she picked up her switch, wiped off Pen’s blood, and crooked her finger at Char.

Char was the hardest. By far. Despite the fact she had come to him, assigned by her mother to destroy him in the eyes of his father—a mission she had accomplished spectacularly—she had become fond of the boy. Of course, she had! What kind of a person could get to know a child, without coming to have sympathy, and even, eventually, the beginnings of love for him? Ha! She knew the answer to that: Her mother… her mother, whose coldness and harshness weren’t quite human. Ironically, she thought, not for the first time. It was her mother who had conceived of the assignment, then insisted on Sindonie performing it, and finally become restive and frustrated when it became obvious a bond was forming between them. But she, who had been sent to destroy, had been sent to him in the guise, the role, of a caregiver. Her mother was crazy to expect—to expect she could just—be inhuman.

Just as Phillipa’s and Roger’s reactions had informed her severity with Big Ed, her treatment of her first victim had become the benchmark of her treatment of her own boys. She could hardly show them more mercy than Big Ed: that would be the exact opposite of what she was trying to accomplish here; the absolute opposite of what her boys needed. She had to do what she could to help them. And today that meant hitting them as hard—at least as hard, but the last thing she wanted was to hit harder than necessary—as she had hit Big Ed. Her poor little baby barely lasted two strikes before he was bawling. But, setting her jaw, she did what she had to do.

Having been saved from disciplining her own son, it was inevitable that Char would have been the hardest, simply because she felt so much more for him than the others. But what really tortured her, like a spike in the gut, what really caused nuns and children alike to gasp in shock, was the evidence of what had happened yesterday. For this was the second time in as many days the poor boy had been beaten. No matter what she did here today, in terms of actual damage, she was sure her blows were nothing compared with Baron Wrathdown’s brutal assault with the flat of his sword had wrought. The switch was an instrument meant to cause pain rather than permanently damage flesh. And it would have hurt awfully enough; certainly its sting was more focused and intense than that of a sword. But coming on top of the physical damage of yesterday…

She heard a couple of moans arise from the children behind her at the sight of Char’s nearly-blackened, badly-swollen, bottom. When Phillipa leaned forward to see better what the children were reacting to, she looked horrified. “Oh no,” she shook her head. “Perhaps, after that—we could…?”

“No,” Sindonie answered firmly, letting her gaze run over each of the children again before she met Phillipa’s eyes, and then turned her attention to Char. “Char sugar,” she said softly, “I’m going to kneel on your shoulders, honey, because no human can be asked to stay still for this.”

“Yes, Miss Sindonie,” Char’s voice shuddered with fear.

“I love you, sweetie. It’ll be over in a few minutes.” And she petted his hair, a curiously incongruous action, a moment before she began whipping Char with all the same force she had used on the other boys, instantly drawing more blood in her first blow than she had drawn from the other two boys combined. Mother Phillipa’s jaw dropped and she looked away, unable to bear it and clearly unable to even continue her own work until Sindonie had finished. By the time she was done, even Pen had fallen silent and still under the same dread spell that had affected the others.

The moment she was done, Mother Phillipa—who’d obviously been counting, said hurriedly in one nonstop phrase: “I’ve got the rest of them please go take care of that dear boy!” Sindonie nodded, cradling him carefully in her arms by his shoulders and the backs of his knees, carrying him to her own bed and laying him down on his stomach so she could tend to his wounds.

Some of the children had fled the room. Roger and Rose would never do that; they were practically incapable, after whatever they had suffered in their short lives, of running away from anything. They would, Sindonie suspected, face down the devil himself no matter how scared they were, out of simple, unthinking, ingrained obstinacy. Perhaps because they’d become convinced there was no way for them to escape the oppressive pain of the hurts done to them? She could relate to that.

But even Roger and Rose looked more unsettled than anything else, hardly noticing Lucky Martin’s punishment at all, even though it took place directly in front of them. And when she started on Ollie, what brought their focus back on current events was Sindonie’s boy’s utter stoicism. Oliver hardly even grimaced. His face was set in dogged determination; no one would mistake his posture or expression for disinterest or detachment. He was working. But he was succeeding where no one else had. As Sindonie had known he would. It was anybody’s guess whether there was a bit of moisture in the corner of one eye when he stood back up, stiffly but deliberately and with a challenging gaze staring down all the other children except Roger and Rose. Certainly Cutter and Fulke and the Martins and Big Ed, who felt ashamed that their own performances had come up short of his.

When she was finished, Mother Phillipa shook her head. “It’s normal to cry,” she advised him. “You’re only the second boy I’ve ever had who didn’t cry.”

“Third! Third boy or girl!” Rose growled angrily, feeling slighted. Phillipa and Sindonie shared an amused glance, that the girl would have felt the urge to make such a claim.

Phillipa shrugged, wrestling with how to respond appropriately. “Sometimes,” she finally allowed, deciding sensibly to minimize it and move on. “Let’s say second-and-a-half.”

Looking more suspicious than mollified, but not quite sure how she ought to feel, Rose stared at her a moment longer before turning around and preparing to march out of the room, announcing: “Nothing more to see here—” until her eyes fell on Pen in his cage and she grinned, turning to approach him.

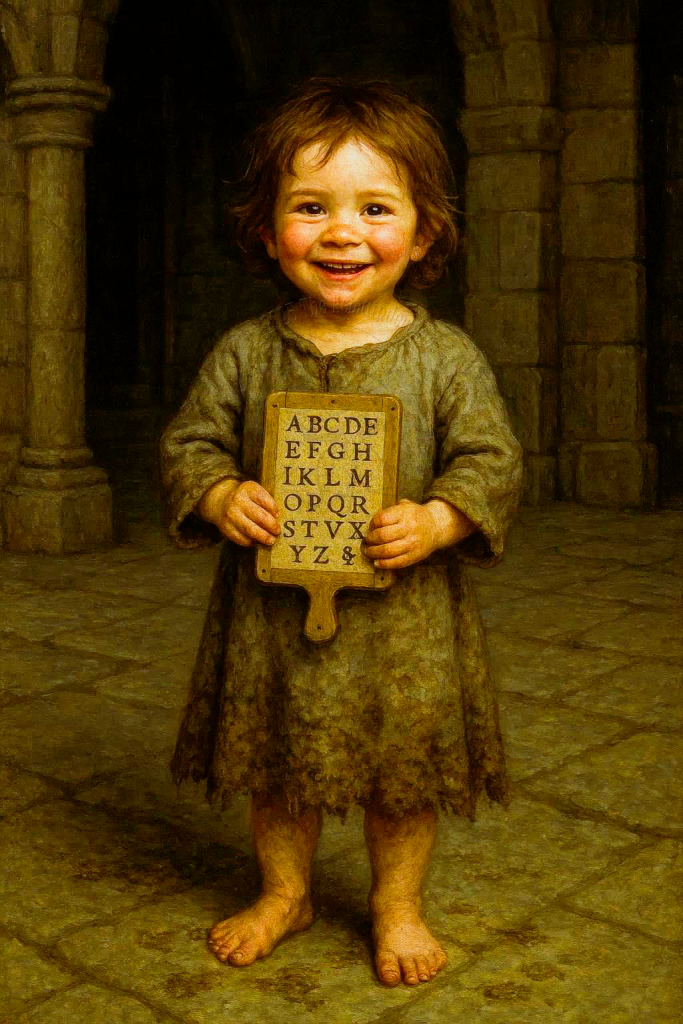

“This isn’t Pillori Place!” Mother Phillipa reminded her. “Move along. You have class anyway. Sister Mary will begin with letters in just a minute, and if Hard Henry wants to teach you—” she tried not to laugh, she really did, but the absurdity of surly rebellious Rose cooperating well enough with anything was so manifest, she snorted anyway, seeing Rose react all the more stiffly because she knew Phillipa’s amusement was sincere rather than mean. Controlling herself, she tried to finish what she had begun, an effort to convince Rose to try, however hopeless a case she might be: “If Hard Henry wants you to learn Latin, you’ll need to know all the letters first. Which you should have learned at least two years ago,” she opined. “Even you should be able to manage it at this age, if you give it a try.”

Sindonie whispered at Char to give her a minute, promising him she’d be right back, and then she went to hug Oliver tightly, smiling encouragingly at him as he shrugged her off assuring her: “I’m fine, mom!” and sounding slightly exasperated. She bit her lip to keep herself from smiling, but Roger saw it, even though his eyes were mainly, and thoughtfully, fixed on Oliver, evaluating him with the respect he had just earned.

“Cutter, you weak little rabbit!” Roger sneered at the slightly-younger boy, shaming him. Sindonie took it as a good sign he picked on Cutter instead of one of her own boys. Apparently, at worst, the freak show her three boys had put on left Roger nonplussed; at best, perhaps he had decided their performance at least the equal of his old companions. “Hard Henry’s waiting for us. Are you ready or do you need a minute to cry in Mother Phillipa’s skirts?”

“Roger!” Mother Phillipa sighed in exasperation, as Cutter hurried toward the door.

“Look, please don’t tell Hard Henry—”

“What, that you cried like a girl?”

“I will if Roger doesn’t!” Rose laughed from the hall, before disappearing out of sight.

“I want to give Char a gentle bath and bandage him properly,” Sindonie announced. “You looked worse than yesterday, poor baby, even before I started.”

“I’m fine,” Char tried to protest, in defiance of all the evidence.

“It’s sepsis I’m worried about,” Sindonie confided. “Not your feelings. I know you’re tough, sweetie,” she assured him. And when she saw Phillipa approaching Pen’s cage, she asked: “How’s my other boy doing?”

“How are you doing?” Mother Phillipa asked kindly. And when he didn’t respond, she asked: “Has your reason returned? We don’t use the cage for punishment. Not when I’m in charge. We use it for control, as a last resort for children who’ve lost their wits.”

“I haven’t lost my wits, Mistress,” Pen managed, his voice tight, doubtless feeling the tightness of the space he was in; as well as the resentment that was written openly on his face. “I didn’t,” he clarified.

“We’ll have to disagree on that, Pen. But you seem fine now, so I’m going to let you out. Are you ready?”

“Yes, Mother Phillipa,” he tried not to sound too angry, with a limited degree of success. When he came out, all but shaking himself free of her hand when she tried to help him, he was stiff from the confinement, and stretched, slowly and tentatively, pursing his lips. Whether he was trying to hold his tongue from sharp words or sounds of pain, neither woman could quite tell.

“We know you’re still affected by… what happened to you, Pen. But that was not a normal reaction to being punished.”

“It wasn’t?” He asked, sounding both angry and surprised.

The women laughed. “Of course not! You can’t be telling us you react this way every time you’re punished?” But Pen looked troubled instead of answering, gently touching his own bottom through his dress to see how tender he felt. Apparently, he felt quite tender. And something about the way he was reacting prompted Phillipa to ask: “I mean, you’ve certainly been punished before!” And when he looked disconcerted, her voice went up: “You have, haven’t you?”

“No! Why would I?”

“Why?” this was a question Phillipa hadn’t expected any more than the answer. She and Sindonie exchanged a quick smile when they heard Char giggle, despite his own suffering. It was preposterous, but Char didn’t seem to doubt it. “To correct you, of course! To teach you a lesson!”

“I learn perfectly well with my eyes and ears, Mistress! My bottom doesn’t normally come into it! Except,” he mused ruefully, “Normally I use it to sit on. Being sore is going to make it that much harder to think about my lessons.”

“Well—well—” Phillipa huffed and gave up, shrugging hopelessly at Sindonie and then snickering unintentionally at the twinkle in her eyes. “That sounds—just—agh! Quite reasonable, actually, sir.” She shook her head, covering her smile with her hand. “Is the Pale really that different?” She asked Sindonie. “Perhaps we should relocate the school there.”

“Closer to the moon than the Pale,” she shook her head, circling her finger beside her head in the universal signal for crazy. “Are you sure he has his wits back about him already?”

“He seems to. Pen, in my experience, some children can only seem to listen with their ears after feeling the switch. And you attacked other children last night.”

“They attacked us!” Pen whined, then fell silent when she looked at him dangerously.

“You don’t seem to be listening.”

“Yes, Mother Phillipa,” he grumbled, forcing himself to accept her words.

“I saw you with my own eyes. Our Savior taught us to turn the other cheek. That wasn’t what I saw you doing last night. Nor merely protecting yourself.”

“Yes, Mother Phillipa.” Sindonie bit her lip; she wasn’t sure she agreed with turning the other cheek, not in this world. Not when they posed a genuine menace. But she wasn’t about to openly contradict the Augustinian.

“Show me you can learn with just your eyes and ears. Set an example for these other boys and girls. Please!” she urged. “Show them how gentle folk behave.”

Something—perhaps the memory of ‘gentle’ Roland Wrathdown viciously assaulting his own son with the flat of a sword, Sindonie thought cynically, then pinkened as a traitorous thought linked what Roland had done to Char, to Sindonie’s own treatment of the boys here this morning—flickered over Pen’s face before he nodded and agreed: “Yes, Mother Phillipa.”

“Pen, come help Char,” Sindonie suggested.

“Yes, Mistress,” he agreed, his eyes softening as he refocused from his own anger and resentment on his concern for his… friend? Or at least, traveling and sleeping companion.

“I can’t carry him down two flights of stairs without holding him by the butt, which would hurt him. So I’m going to walk in front of him and I want you to walk behind him holding his arm while we go down the stairs.”

“Here,” Mother Phillipa offered, catching up with him as they reached the stairs. She had dipped a corner of a sheet in water and used it to wipe the sweat and blood from her prayer bench. “You can hang this sheet up for privacy. Use the lower clothing-line. We keep the children too young for class in the kitchen during the day.”

When they had a moment on the second floor, standing aside so others could use the stairs before they continued their slow descent the rest of the way, and no one was nearby, Sindonie pulled their heads close to her own and told the boys she was sorry for what they had endured, kissing each boy behind his ear. “Have you really never been punished before?” she asked Pen, wide-eyed.

“No!” he said insistently, shaking his head and looking frustrated not to be believed. “That was—that was horrible!” He shuddered, and with a soft laugh, she hugged him tightly again.

“Poor baby. My poor babies.” It occurred to Sindonie, with a sudden surge of excitement, that her days of feeling conflicted about Char might be over. Now that he—now that all three of them—had been banished, by her brother-in-law and her own mother, to this place far from Wrathdown, and the father had committed his son to the church, she could simply help both of them. That was, after all, her sole job. And her mother was not around to cluck and hiss with disapproval anytime she showed her feelings for the child. No duty to conflict her, and no nagging social pressure.

She hadn’t spent her whole life pining for children, the way some women did; but she had been happy enough to have little Oliver, despite the terrible price of it. Of him. No, of it—she didn’t reckon little Ollie asked her for anything beyond his life, and the love of his mother, both of which she’d been so happy to give. The price demanded—that had all been her mother’s fault, just a further weight of sin to add to her dark balance. And if asked how she would have liked to spend her widowhood, well… she knew where she belonged, but she wasn’t quite sure she wanted that. She’d never signed up for the path her mother had set her on—forced her down, to be more honest. And while she’d managed to find joy in the work despite her mother’s best efforts to make her entire life a misery, and despite the constant fighting with her and—and the others…. Still, it was hard to accept her mother’s orders when it came to establishing her own identity. She had always defined herself in opposition to her mother—not in acceptance of her.

So…. More traditional paths. And very likely (despite the hazards of life on the Pale), safer paths: Wrathdown with Roland, or Skremen with Lady Parnell? Neither option was thrilling, to tell the truth. And marriage would never be an option for her again. But if she’d stayed in Wrathdown—or if her mother had stayed in Wrathdown, and she’d gone back to Skremen—she wouldn’t have minded a relatively easy life, helping around the household without primary responsibility for anything, perhaps finding something to do that actually interested her.

It wouldn’t have been acting as a governess for other people’s children. And certainly not in a charity house for a bunch of vagrants’ children in a Dublin slum. In a slum? It was a slum! By itself. Practically by definition.

But the prospect was not… nearly as bleak as she once might have thought. But only if she could find a way to protect herself from the church all around her here, like a coiling snake, wanting to hold her in more tightly when she had spent her life navigating between the church and her mother, in an effort to be herself.

Confession?! The thought still took her breath away in a burst of panic. She had to find a solution. And fast.

Sister Phillipa, ushering Ollie in front of her, rejoined them on the first floor a few minutes after the tub had been filled with warm water and the boys—both of them—had settled into the warm water, grimacing and groaning as they tried to be comfortable.

“You caught me,” Sindonie pinkened.

“What?” Phillipa asked, then smiled when she realized she was referring to Pen’s presence in the tub. “Oh. I guess I did.”

“I’d put all the poor boys in here to soak if I could. I’m not even going to ask you, Ollie,” she rubbed his hair. “Because—”

“No!” he shook his head.

“Men!” Sindonie shook her head.

“I brought Ollie because I realized you arrived so late, I didn’t get a chance to welcome you to Charite Hous, and explain the rules. Although—” she raised a finger towards Pen, as if he were likely to argue with her, which perhaps he was “Not fighting is a rule that should not require any explanation. First rule, no fighting, no locking children in beds or other boxes. What?!” she asked Pen sharply.

He slumped. “What about cages?” he murmured.

Phillipa and Sindonie exchanged a scandalized look. “I can see you were accustomed to a high-handed life on the frontier, but you do need to show respect here. We’re… much more crowded together, for one thing. It’s difficult enough for us to get on, on our best behavior. And if you cannot learn that lesson with your ears, I will find a way to teach it to you.”

“Yes, Mother Phillipa.”

“Second rule: Don’t leave the orphanage. Unless you’re accompanied by an adult, or you have an apprenticeship outside the orphanage, the Charite Hous and the privy behind it are the boundaries of your entire world while you’re hear. You are not to step out the front door, or to open the front door, or even to speak to anyone through the front door. You are not to step into any of the other buildings that share the privy, or any of their areas outside. If you haven’t used it yet, you’ll discover there are several privies out there, but there’s a fence separating us, and our privy, from those of the other buildings. You’ll notice it’s meant to keep adults out, not children in. Don’t try to wiggle through it. If anyone tries to talk to you through the fence, you come inside and report it. We have some unsavory neighbors. They are not sufficiently responsible to speak to our children.”

The boys exchanged a look. “There’s barely enough room to open the doors of the building, or of the privy,” Oliver advised them. “Definitely not both at the same time.”

“Third rule: Obey the adults. I probably don’t have to tell you this, but for many of our children it’s something that has to be explained because their life experience is to the contrary: The adults here, are here to help you. Even when we discipline you. No one’s here because they resent children or want to hurt them. They’re here because they want to help.”

“Fourth rule: Apprentices get first access to everything in the morning, so they can get out to their placements. And, it’s generally a good idea to avoid them as much as you can. All of them are too old for this place, really, but I don’t have the heart to kick them out on the street if their master won’t house them during their first three years.” She didn’t explain, what they perhaps already had but certainly would figure out, that it was the worst of the children who were the least likely to be offered housing by their masters; or to be chased back to the orphanage after failing to get along with whatever was required of them in their new homes. Instead, she skipped to effectively the same warning: “And many of them learn rough ways—adult ways—from their Masters, and come back here thinking they’re too old for our rules, even though they don’t consider themselves too old for our charity.”

“Fifth rule: Everything has to be cleaned, and everyone has to bathe, at least once a week, whether they need it or not.” Sindonie snorted, unable to contain her amusement, and Phillipa smiled faintly. “Especially boys.”

“Amen,” Sindonie agreed.

“Dublin—well..”

“It stinks, Mother Phillipa,” Pen prompted flatly, emphasizing his distaste for the smell with the emphasis placed on his words. “Every second!” he shook his head unhappily.

“It… It really does,” she nodded. “It well and truly smells awful. I’ve lived here my whole life, and even I can smell it when focus on it. I don’t know what St. Thomas Aquinas would have to say about it, but in my lowly opinion, it stinks for the same reason it’s infested, and it’s infested for the same reason it’s filled with sicknesses: because it’s dirty. Bathing and cleaning are the only defenses I know to either scourge, and we’re too crowded here to avoid any risk we can avoid of infection.” She shuddered at the thought.

“Sixth rule, and this one is always in progress: when we see someone who needs help in our house, we help them. Again, something that should be obvious but that many of these poor children have never seen. Our goal, our mission, is to keep as many children alive as we can; and to prepare them for trades so that they can support themselves when they leave. Everyone here is expected to share that mission, by doing their chores, following the rules, and helping others.” She shook her head and huffed. “It’s why I take fighting so seriously. You were not welcomed into our community the way you should have been. And doubtless you will discover many of your fellow orphans are too mean or simply too ignorant or broken to be helpful. I can’t really enforce a rule for helpfulness, but I can enforce a few rules about limiting harm.”

Literature Section “08-04 Painful Reckoning”—more material available at TheRemainderman.com—Part 4 of Chapter Eight, “The Wild, Wild West”—12,867 words—Accompanying Images: 4599A-B, 4600-4604, 4605A-B, 4606-4613, [and on 2026-01-8: 4650]—Published 2026-01-29—©2026 The Remainderman. This is a work of fiction, not a book of suggestions. It’s filled with fantasies, stupid choices, evil, harm, danger, death, mythical creatures, idiots, and criminals. Don’t try, believe, or imitate them or any of it.