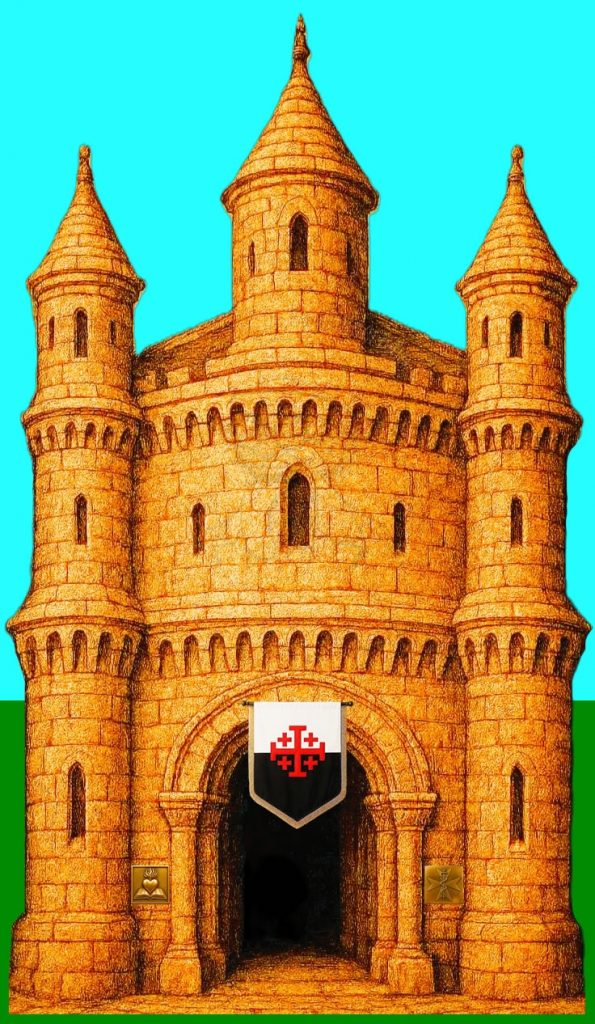

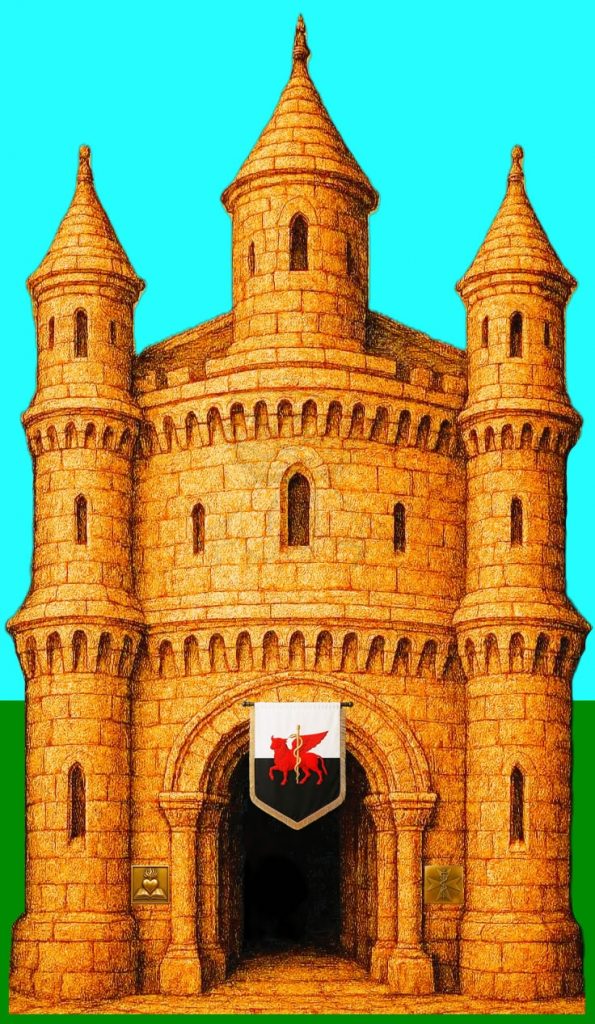

4580 08-02.5 Shanganagh Castle on the Pale, A.D. 1516

CAUTION: Contains themes of child and domestic abuse, misogyny, and bigotry some readers may find disturbing.

PREVIOUSLY: Two traumatized boys of 5 or 6 residing on the militarized Southern border of the Pale have just been given into the care of the Augustinians: Char, youngest son of Lord Wrathdown, a gentle nontraditional boy and a bit of an airhead, has been banished to the Church to make a man of him; accompanied by a new ward of his father’s, Pen, the refugee of an Irish raid, who was meant to help him learn, but is still in a state of shock from whatever he has experienced there. NOW:

“Stop nattering. You’re as nervous as a cat,” Archbishop Andrew chided Friar Hugh mildly, as his clerk, Friar Paul, sitting across from them, stifled a smirk. Friar Paul was doing his best, in the jolting carriage, to draft a letter the Archbishop had just begun dictating to his superior, Cardinal Wolsey, and the Royal Almoner Richard Rawlins, the Archdeacon of Cleveland. Despite his best efforts, Paul knew he would be up all night redrafting every word and sentence dictated on the ride to make them both legible and suitably formal and neat for the dignity of the Archbishop’s office. This latest letter especially, as it was to entreat the second- or third-most powerful man in the British Isles (depending on how you rated him relative to James V, King of Scots, who was approximately the same age as the two children squeezed into the bench on either side of Friar Paul at the moment).

One of those children, the young lord of anything that remained of Raheen-a-Cluig Manor, was suitably impressed with the eminence of their company to remain silent, and had not spoken a word except when spoken to on the long ride from Dublin except when the Archbishop led them in their prayers at Prime and Terce—again, the prayers were a much longer version of what Char was used to at home. “But at least,” the Archbishop observed jovially, “The lad is speaking, and observing his manners!”

The other child, reflecting both the short but privileged life of relative deference he had enjoyed before this morning, and his increasing excitement at returning home, could not have been shut up by the Beefeaters themselves. Although even he seemed to be sobered by the solemnity of being privately led in the Divine Office by the Archbishop of Dublin. For each office, their little caravan stopped, Andrew donned his stole and miter, and then he read the service from his seasonal Breviary. It doubtless helped impress the children with his dignity, the awe with which other travelers on the road reacted, and fell to their knees reverently, the moment they caught sight of the Archbishop in his regalia leading the service beside the road, offering coin, grain, or anything they had in gratitude and awe when he was done. Their reaction was even more striking than the reaction to the Archbishop’s cart, which was satisfying enough: once they’d passed Milltown, they’d left the Slige Chualann, the great Southern road from Dublin, which veered West around the Wicklow mountains. They were then back on the local roads (well, the local road, which most people South of the capital called either the Ród Dubhlinn or the Ród Bré because it was the only real road in the narrow tongue of land jutting South along the coast from Dalkey to Bray, tenuously held by the Baron of Wrathdown, and therefore the King of England, despite the slow erosion of English power in the Pale, and more broadly Ireland.

Theoretically, a ród should be wide enough for a wheeled vehicle to pass two horsemen without any of them having to leave the road; and therefore, by implication, suitable for a cart. But the estimation of most people seemed to be quite different from that of whoever had laid out the road and labeled it a ród. The few people they passed—most on foot, a few on horseback, absolutely none on a wheeled vehicle of any kind—stepped off the road entirely to avoid being run down by the horses pulling the carriage, when the boundaries of the road were even clear enough to make out. They tended to be clearest where the road ran through bogs. There, traffic was constrained to follow eskers—narrow, winding ridges of sand and rock—or, rarely, relatively-straight rows of wooden planks laid out to keep travelers from sinking into the wetlands beneath them. The boards often appeared, and many of them may have been, more ancient than the walls of Dublin themselves. But in most areas, the “road” was more of a traditional easement, a legal right of the public to transit land, than a physical construction or even a physical scar on the land.

Fortunately for the passengers in the carriage, they couldn’t see the dread slowly gather in the driver’s face when leagues went past without seeing another human face, or another unambiguous confirmation—like wooden boards—that they were still on the right track. The driver had confidently asserted he could drive them anywhere in the Pale, thinking they had meant anywhere people in their right mind might want to take a carriage. Driving in Wrathdown was frightening enough in its own right, being as close to the border as the entire half-serjeanty was. But once they were off the Slige, his fear was compounded by the nagging question of whether he was still on the correct route, or might have accidentally left the road. Especially, if he might have left the road and drifted toward—or over—the boundary itself, perhaps in an area without any signs of fortification. The longer it went on, the more anxious he would become that they were surely in the terrifying O’Toole’s wilderness, far from civilization and doomed.

Relief would sweep over his face, more animated even than the surprised faces of people setting eyes on the carriage, when he would spot an English farm or village, or English travelers—obvious from their clothing, and even the way they rode their horses—reassuring him they were still on track; and offering him another opportunity to ask for guidance and reassurance about the next stage of their journey.

“That’s Uncle Owen’s farm!” Char suddenly exclaimed, pointing out the window. “I don’t know why they call him that,” the child added, apropos of nothing. “None of us are related to him. We’re almost there!” he exclaimed at that very moment, half-hanging out the window both for fresh air and to entertain himself. “This trip was so much faster!”

Father Hugh’s mind was elsewhere. “It’s just—Baron Wrathdown is… you may not appreciate how…” he flustered, “well, irascible he’s become, doubtless as a result of his beloved wife’s passing—”

The Archbishop made a sound of disgust. “His bereavement has nothing to do with it. Baron Wrathdown is a bully and a thug, always has been. Like all the Wrathdowns. Er, so to speak,” he added as an afterthought, gesturing towards Char as it occurred to him he was one of the Wrathdowns, the closest to an apology for insulting him and his entire family as he had any interest in making to the child.

“That and worse, my Lord. He’s a beast!” the boy agreed, his nostrils flaring with hostility, causing the Archbishop and his clerk to laugh. Something in the Archbishop’s eyes, though, reflected his displeasure at the child’s ill manners—speaking out of turn, speaking ill of his own father, and speaking ill of a significant nobleman—and promised to remember it for later, once the boy was well and truly his. But time was on his side, he was nothing if not practical, and at the moment, mere minutes before facing the boy’s father, he gauged his own interests were best-served by winding the child up rather than putting him in his place.

Friar Hugh nervously stumbled into the silence left by the prelate’s wintry calculations. “It’s just—I’m afraid if you haven’t dealt with him recently you may not appreciate his state of mind—”

“Good heavens, man, don’t soil yourself. You were assigned here—well, mainly because nobody else wanted to be—but it’s a post that’s expected to toughen you up, not break you down. I admit, I don’t relish this visit any more—well, too much more—than you do, but I’ve been dealing with the Marcher Lords, including Wrathdowns, my entire adult life. And it’s best to do so when there’s something they need.”

“I—I don’t know how he’ll react—”

The Archbishop of Dublin showing up unannounced for his first visit… well, ever? He’ll shite himself, the Archbishop thought, but kept the thought in his head, contenting himself with a snort of amusement. “We’re about to find out. You can stay in the carriage if you lik—” the carriage suddenly jolted with unusual force, and the Archbishop used his crozier like a knocker on the roof. “Try to stay on the road, man!”

“Yes, m’Lord, I’m sorry, m’Lord!” the poor driver responded, not for the first time on their long drive. It was the only thing he really could say, despite the unfairness of his lord’s complaint. Of course, he hadn’t veered off the road; the muddy track was just that bad, and getting worse with every mile they ventured from Dublin. The threat posed by the wild Irish wasn’t the only reason the Archbishop was more likely to travel across the Irish Sea to Chester, Bristol, or even London, than he was to visit the border parishes of his own province less than a day’s ride South of his Palace. It was 10 miles to Shanganagh, the matter of 2 or 3 hours by carriage on a real road; very close to 5 in the actual conditions prevailing today. The drive was made worse by the fact the bishop had semi-commandeered a rental carriage—little better than a roofed cart with benches—from a fawning merchant staying at the King & Lord Henry VIII In across the street from the cathedral, rather than stopping at his palace at St. Sepulchre to risk his own, more-comfortable carriage on the so-called “road” to Bray.

Detained in the City by his deliberations over the boys, his quick decision to visit the Baron the very next day, and sending a summons to Dublin Castle requesting an escort for their ride, the Archbishop and the children had all slept with the brethren in the men’s dormitory at Holy Trinity Within. Char, exhausted as he was by his unimaginably long walk the previous day, mainly remembered the night for its interruptions: being dragged, sleepy-headed, out of his warm bed by candlelight to pray for Vigil, and then later Matins, which were both said by the brothers right there in the dormitory.

In the morning, the Archbishop had only tarried long enough in Dublin to say Lauds and break his fast. By the time they walked out of the Friary and across Pillori Place to their carriage, waiting in front of the King & Lord, their City Guards were waiting for them: an officer and a man familiar with riding horses, and two other soldiers who would spend their day holding on for dear life behind him. All four of them were intimidated by being invited into such close company with a personage as august as the Archbishop; and they were many miles and hours South of Dublin by the time their language and complaints returned to something like their normal coarse language. At first, they were as quiet and careful as Pendragon.

“Child, pull your head back inside the carriage and keep it here as we approach Shanganagh,” the Archbishop growled. When Char obeyed him, he said: “When we arrive, I will exit the carriage and at that point you can look out the window and tell me who’s come to greet us. Then you should try to be as quiet as your companion. Do you understand?”

“Yes, My Lord.”

“Good.” And with that, he resumed dictating his letter while Char and Brother Hugh fidgeted with nervous energy, and Brother Paul tried manfully to produce writing he’d be able to read when he copied the letters tonight.

“That’s Lady Parnell!” Char reported excitedly, just before making a gagging sound, as the Archbishop clambered down, assisted by his dismounted driver. “My father is horrible!” the boy moaned, sounding as if he was trying not to wretch. The Archbishop’s eyes flicked quickly to the source of Char’s distress—three severed Irish heads hanging from the ornaments over the castle door, and another good dozen, he guessed, from the battlements four stories above—and just as quickly away. He much preferred to watch carefully, and with satisfaction, from about ten feet away, at Lady Parnell, as her eyes, fully acclimated to such everyday gruesome scenes as Irish heads, widened in confusion and surprise at the unexpected sight of her step-grandson’s face sticking out the first carriage to be spotted at the frontier… well, ever, like as not; and then, with even greater satisfaction, as her eyes dilated to the size of plates registering the Archbishop’s robes.

The normally-unperturbable Lady Parnell spontaneously raised her hands to the sides of her head and screeched, literally screeched, in nervous surprise as the Archbishop, so pleased he was hardly able to maintain a straight face, approached her, extending his arm. Baroness of Skremen she may be; but the road from Dublin to the frontier, as short as the flying crow might reckon it, connected two very different and separate worlds. She had been to Dublin many times, and of course met the Archbishop; but in decades of life at her own husband’s border fortification, her time here at her son-in-law’s, and at her father’s castle when she was young, she could have counted on the fingers of one hand the number of occasions anyone other than a working knight—a proper soldier, who lived and profited by raiding and fighting—a poor tradesman, or or a parson, had found themselves with business requiring their attention among the yeomen along the Pale.

As she knelt to kiss his ring, sounds of commotion erupted from inside the tower as people called out questions, asking what was happening. A younger woman—Char’s step-aunt Thomasin—came hurrying to the castle entrance and froze, her reaction as pleasing as that of her mother as she cried in amazement: “It’s the Archbishop!!!” She practically fainted. Andrew doubted the Pope himself would have received more acclimation. Children who had been playing or working around the barn or in the castle ran up to the carriage and inspected it in awe. None of them had ever seen such a thing before, or—many of them—even imagined it. The only vehicle any of them had ever seen pulled behind a horse was a plow. Even adults looked at the carriage like it might come alive; children who weren’t held back by their mothers universally stepped forward to run their hands over the polished, coated wood.

“WHAT THE SARD ARE YOU CURSED WOMEN ON ABOUT?!” came the unmistakable bellow of Lord Wrathdown from just inside the castle, at the very moment the Archbishop entered the tower and was brought to an abrupt halt by the sight before him: Roland standing unapologetically, very nude, reeking of sex and dripping with sexual fluids, vulgarly layered on top of the smell of death and dried blood that still stuck to him from the road and the battle two days earlier, holding a piece of turkey in one hand and a stein of beer in the other. His wife—one presumed it was her, from her state of pregnancy and blond hair—stood behind him, half-hugging and half-hiding, wrapped in a royal blue blanket. And as if that were not enough, an utterly naked woman clung to Roland as if she needed his strength to keep her unsteady feet. A raven-haired barefoot beauty with a contemptuous smile on her face and an entirely metaphorical whiff of brimstone surrounding her sat near the top of the stone stairs to the castle’s upper floor, wrapped but not actually quite dressed in a fine black silk dress. At the sight of the Archbishop in his full regalia, contrasting with the Baron in his, she burst out laughing: a sharp and cruel kind of amusement at the expense of everyone comprising the tableau below her.

Walking in immediately behind the Archbishop, Char and Friar Paul likewise stopped and stared, astonished but able to absorb the tableau before them; while 3 servants in well-worn but well-cleaned uniforms focused as intently as they could on their business of cooking porridge for dinner and stoking the fire of the great hearth, pretending they were unaware of anything else happening in the room. Nonplussed, in all its meanings, the Archbishop gathered Lord Wrathdown had been indulging in a bit of brazen post-indulgence snacking when they arrived, his state of in flagrante arrogance signaling at once his total mastery of the castle, and the total contempt in which he held everyone else in it. From Char’s reaction, unhappy but unsurprised, the Archbishop gathered this was business as usual at Shanganagh, the Baron knowing his capacity for violence was sufficiently great, and useful to the powers-that-be, that he had nothing to fear in his own domain.

And, indeed, the Archbishop had little enough interest in trying to assert his ecclesiastical authority to improve the man’s behavior towards his miserable subjects; or to elevate the moral atmosphere of the Southern frontier of the Pale at all, except insofar as the parish priests under his jurisdiction might be able to assist the willing faithful. His interests in the Baron were limited, practical, and entirely instrumental. Pendragon and Brother Hugh were the only two people present who reacted in a manner the Archbishop would assess as natural: They walked in, looking around with curiosity; and the moment they caught site of the Baron and his harem, they turned on their heels to head back the way they’d come. It was a lot easier to ignore bloody hanging heads when you could look anywhere on the beautiful green Irish horizon, than it was to ignore the Baron’s retinue inside the crowded space of the castle hall. The Archbishop let Brother Hugh go; heaven knew, the man had to spend enough time here. But he required the orphan for his planned theater, and so without either missing a beat or looking away from the Baron, he caught the boy’s arm and yanked him back around to stand, stiffly and uncomfortably, with his eyes determinedly on the floor.

“GOD’S TEETH! WHAT THE SARDING HELL IS GOING ON?!” Baron Wrathdown bellowed, blinking as if trying to clear eyes which must be misleading him, and sounding not quite fully alert, as if perhaps he had just woken up but the ale in his hand was not the first of the day. Belatedly noticing his own child standing next to the archbishop, he stabbed his finger at him and asked, dismayed: “WHAT THE SARD IS THAT LITTLE BAEDLING FARTER DOING HERE?!” Lady Wrathdown was cringing with a look of combined alarm and embarrassment; and perhaps it was only imagined, but it looked for a second as if she tried to distance herself from her husband, either to get out of the line of fire, or to remonstrate with him. Whatever her intent, her efforts were no more availing than those of a fly trapped in the crook of the Baron’s arm. The other woman was making a pained expression and trying to cover her ears, which seemed to be about all she could manage, or dared.

Archbishop Andrew made the sign of the Cross and murmured a quick prayer of forgiveness before answering, calmly and with uninterrupted poise: “I’ve brought them back.”

“YOU WHAT?!?!” The Baron thundered, astonished at what he had heard. “I PAY YOU LOT!”

“And we pray for your quite-imperfect soul, Lord Wrathdown,” his tone making it clear he was neither showing any deference to his host, nor rising to his bait: He raised his voice by a measured amount, firmly holding his ground without matching Roland’s roar. “The Holy Mother Church rejoices at the close alliance we share, and has always welcomed your… sizable family with open arms. We would like nothing more than to bind our community closer by raising your son to his rightful place as brother to his own kin, and all of us in the faith. But young Master Charles here is five or at most six years old, judging by his appearance and our records of his baptism. As, presumably, is this one.” He wagged Pendragon’s arm to show who he was talking about, in unconscious imitation of the Baron’s own conduct the previous day. “And I’ve been informed you specifically wanted to isolate him from the care of women.”

“SHITTING RIGHT I DID!”

“Raising children under the age of seven is strictly… women’s work,” he shrugged and sneered, conveying exactly the right amount of disgust at the idea. Not that he felt it, or much of anything that he appeared to feel. “What do you think of us? What kind of men do you think would be prepared to undertake such work?”

“Wha—well—I—” clearly his lordship hadn’t bothered to think this far before seeking to impose his will.

“Why would you want your son to learn from the kind of ‘men’ who would play nursemaids and nannies to children? What would you want him to learn from such people?”

For a moment—just a moment—the Baron had nothing to say in response; and above them, from the top of the stairs, came the quiet, musical, but unmistakable sound of the raveness’s perfect amusement.

“QUIET, STRUMPET, DON’T MAKE ME COME UP THERE!” The Baron demanded, regaining his voice, without even bothering to turn around and face her. But while she muted her laughter, her face remained merry and her shoulders continued to shake, so thoroughly was she enjoying watching the man she had—presumably—just been sleeping with, be confounded by encountering his rare equal in power. The fact the Baron let a moment more of silence stretch after threatening one of his whores, seemed to confirm the Baron didn’t have anything of substance to say.

The Archbishop seized the opening given him to push the Baron further off-balance: “Children belong at home, or in orphanages; and there’s only one orphanage in the entire Pale, the Charite Hous of Our Ladies of Lesser Mercy, Mary Magdalene and Salomé. Which is, needless to say, operated by nuns and religious sisters. Of course, the church accepts all children in need of care into its loving arms, and we would like nothing more than to embrace young Charles to our bosom, but it is a bosom.”

“Well—yes—I suppose—but he needs FIRM guidance!”

“Trust me, Lord Wrathdown, Sister Phillipa is firm. Very firm. She deals with the most benighted and depraved riffraff in the four obedient counties of Ireland. Well, the English riffraff, of course!”

“Obviously!” Baron Wrathdown felt obliged to endorse that qualification.

“I mean, we speak of brotherhood, but there are limits!” the Archbishop indicated conspiratorially.

“There certainly are!”

“The Charite Hous admits no scurvy Irish jackanapes!”

Shaking the turkey leg in his fist for emphasis, the Baron growled: “Those lazy wifeswappers shouldn’t even be tolerated on English soil!” (By which the Baron meant Irish soil, of course; or at least, the parts of it under English rule. Somehow, Roland felt a flash of insecurity in his intolerance, as if the prelate had subtly challenged whether he was fervent enough in his loyalties.)

“Well, I’m glad to see you’re with us on that, at least,” the Archbishop managed to leave the Baron with the firm impression he was viewed as an unreliable Hibernophile in Dublin, and wondering how he might have signaled a soft spot for Gaels without meaning to. “But the truth of the matter is, we were worried that your request to have him raised by, well, I don’t know if men is quite the right word for it, but anyway, that you wanted to make sure we protected him. Kept him soft.”

“Protected him?!” The Baron demanded, as if the idea of seeking protection for his child was inconceivable to him.

“The Charite Hous is filled with rough children, Baron. Very rough children, including older children who are apprenticing their way out of the orphanage but whose masters have nowhere to house them.” Out of the corner of his eye, the Archbishop was aware their sultry audience on the stairway’s expression had changed to something surprised, calculating, even a little approving. Although he refused to let himself be distracted, he could admit to himself she was the kind of woman who any man would like to be distracted by. He forced himself to continue: “Since these two lads of yours are of… well, let us say, gentle birth, some of my brothers were concerned you wanted them under our direct care at the Friary prematurely, because you were… troubled the conditions at Our Ladies might be too harsh for them.”

“Troubled—TOO HARSH?!” The Baron erupted back into full volume, but with less rage and more incredulity, clearly having heard the charge of cowardice and weakness that the Archbishop was too smart to express aloud, floating unspoken in the air around his words.

“My apologies for being unclear, Lord Wrathdown,” the Archbishop feigned backpedaling. “Too coarse. Too… plebeian, that’s what I meant to say.” Not quite. “Perhaps you feel such special children deserve a special place.”

“Not this one!” the Baron gestured towards Char. “By the rood, I want this one to man up! As tough as you please!”

“That’s good to hear,” the Archbishop nodded thoughtfully. “But is this other one suited…?” he indicated Pendragon with his hand.

The Baron shrugged in confusion. “What’s that got to do with anything? I don’t give a sard. I just want him out from underfoot! He’s to go wherever my prating fool goes, to bring him along!”

“And that brings us to my other concern, Baron,” the Archbishop confided. “The other children—well, those that aren’t natural Wrathdowns—they’re commoners. Suited for trades, not learning. Sister Phillipa and her staff were perfectly-suited to exercute your instructions to the letter for… the others. But for this one to take on roles in the Church appropriate to a named Wrathdown, the kind of roles that can support you and the older—” flicking his eyes briefly at Lady Wrathdown’s protruding belly—“er, other children of your name as he matures, he needs more education than the Charite Hous can provide him without additional staffing.”

“Oh, I see!” the Baron sneered. “This little visit out from the splendors of your fancy Palace in Dublin is really about money!” It was, of course. The Archbishop certainly hadn’t spent the afternoon bouncing around in the unforgiving wooden frame of the carriage as it banged and skidded and lurched and practically shuddered to pieces because he was concerned about the well-being of the Baron’s backbirthed whelp. He had come here, only because the arrival of the rude child in Dublin presented an opportunity to put pressure on the Baron. Andrew was, however, amused by the look of genuine surprise on the Baron’s face, realizing that it had taken him this long to put the pieces together. That was what subtlety and manners got you out on the frontier: unnecessary conversation with the Beast of the Border. “I already pay the Church plenty! Enough that you should come out here regularly to thank me, and invite us to your Palace from time to time!”

The Archbishop couldn’t imagine anything less appealing, but murmured falsely: “Please, let us know when your duties allow you to visit Dublin! We would relish the pleasant company of the Lord and Lady Wrathdown! And how pleasant it is to me, to visit the green” (reiving-clan-infested, he added mentally) “countryside of Wrathdown. I only regret the press of my duties in Dublin and London is such that, just as yours detain you from Dublin, I am unable to tour my Southernmost parishes as often as I would like. But as to ‘plenty’…” he paused, making a pained expression, pretending to struggle to find the right words.

“WHAT?! My coin is just as good as that of any other’s!”

“Of course it is, my Lord! But there’s just not… as much of it as we’re accustomed to receiving from Lords of your, ah, standing and reputation.” So politely had the Archbishop called the Baron a skinting cheapskate that the fact eluded the children and several of the adults in the room, as well. And even the Baron wasn’t provoked to the fury a more direct insult would have elicited.

But he was certainly simmering, a fact the prelate tried to ignore as deliberately as he had ignored the heads over the door. To the extent the Baron would permit it. “Wrathdown BLEEDS gold—and blood!—for our Lord and King, and for the church!”

The Archbishop could see him winding up, and took the opportunity to implant another barb: “As do all our noble Marcher Lords of the Pale. Truly, you know greater labors for our good King than all the Earls and Barons back home! And yet, your peers manage significantly greater contributions to the church than Wrathdown.” The Archbishop laughed as if surprised by a thought: “Why, they are so eager to pay our brothers and sisters to pray for them, we barely have time to squeeze in our prayers for you, my Lord!”

“WHO does? Who pays more than ME!?”

“The Great Lord, the Earl of Kildare—”

“Kildare? KILDARE?!?!” The Archbishop took a step back, surprised by the vehemence of the Baron’s reaction. “He and the Irish—the other Irish, I mean—are the whole problem!” The Kildares and the other “Old English,” as the great Lords and their retinues outside the Pale who professed allegiance to the King were known, traced their ancestry back to England’s original invasion of Ireland centuries before. And having lived so long among the Irish, outside the four obedient counties heavily settled by Englishmen, the English of the Pale viewed the Old English as having become “more Irish than the Irish,” a phrase usually emphasized with oaths or, more often, a wad of spit.

Gaelicized they may be, but unfortunately, Kildare and the other Old English lords wielded more power on the ground than all the marcher lords of the Pale put together; and it was they, not the marcher lords, who usually served as the King’s Lord Deputies of Ireland. Gerald FitzGerald, the present and 9th Earl of Kildare, was the Lord Deputy in Dublin Castle now, having inherited his Earldom, and practically inherited the Lordship in Dublin, from his father. “He manages the Lordship as if it were his own personal fief! For every three shillings awarded to us for maintaining and defending the Pale, he pockets one or two! He SHOULD be the one supporting your province, Lord Dublin! Why don’t you go knocking on HIS door for more coin?!”

All of this was true, and was generally known by the nobility and gentry of the Pale. What surprised the Archbishop was how openly the Baron spoke of it, and criticized the Lord Deputy. Then again, he considered, he should be sure and learn the lesson of this visit: that a man who received a prelate in the raw without so much as flinching knew how badly he was needed to fill the considerable gaps left in the defense of the Pale by the less-than-ideal (and less-than-honest) administration in Dublin Castle. The man was very much, and very obviously, the master of his own house. Put him down as one of the many opponents of the FitzGeralds, then, the Archbishop thought, with a touch of whimsy at his own expense.

But he let none of these reflections interfere with his purpose here today. Looking regretful once again, he added as if compelled to do so: “And then there is the intractability of your vassals, Lord Wrathdown.”

“Intra—intra—They do what I sarding tell them to do!”

“That’s exactly my point, Lord Wrathdown. I know how many souls have been baptized here, and this afternoon I have traveled the roads of this sweet and productive land, and I am in no doubt your people are failing to tithe what they owe!” That much, he reflected, was solid ground. Nobody tithed what they owed, giving the lie to their claims of devotion; except the handful so devout their priests felt awkward dealing with them. It never hurt to remind the sinners, most definitely including the Baron: “When they cheat the church, with your encouragement, they cheat God. And so do you!” The Archbishop shook his head. “I daresay we’re not receiving a twentieth of what the fertile lands God has given to you, return; let alone a tenth. And despite your protestations of generosity, it’s been months since we’ve seen a donation from you. How many months, Brother Paul?”

“Seven, Lord Dublin.”

“Seven!?” The Archbishop gasped in surprise. “That’s more than two quarters without a shilling! BROTHER HUGH!” he bellowed over his shoulder, showing the Baron that he could yell, too, when he wanted to; and thus emphasizing the control he was exercising in speaking to Roland. For his part, the Baron’s cheeks turned a little redder than their usual lusty luster, and he shifted unconsciously, seeing already where this was going and trying to decide how to respond when he had to.

“Yes, My Lord?” Friar Hugh came hurrying back in, with the same nervous look that maintained a near-constant occupation of his face.

“Have you taken it upon yourself to alter the mass?”

“NO, My Lord!” Father Hugh gasped, horrified and alarmed, wondering what he had done wrong.

“According to Brother Paul’s records, the souls in your care have not been supporting the church. Have you taken to skipping the offering? Have you checked to ensure your donation box doesn’t have a hole in the bottom? Do you think the church can function on miracles alone?”

“No, My Lord! I mean—yes, the offering box is—I mean—” Father Hugh looked like a rabbit caught between a snare and a wolf. Since the commoners were expected to tithe, inquiring about offerings right in front of Lord Wrathdown was perilously close to insulting him and his court. But ensuring the faithful demonstrated their devotion was also part of Hugh’s duty to the church. “Times are hard in Wrathdown, My Lord! I—”

“Times are always hard in the Pale, parson! If you’d remained here instead of bolting, you’d know we covered that topic already!” The Archbishop snapped his fingers repeatedly in front of Brother Hugh’s face, really beginning to enjoy himself and thinking the damned ride down here had almost been worth it. He considered slapping the friar right here in front of members of his congregation but decided to deal with him later. “Try to keep up! If there are no Christians in your flock, your services won’t be needed down here any more!”

Now it was the Baron’s turn to step back, the gesture positively manly compared with Brother Hugh’s cringing posture and face. Roland Wrathdown knew a threat when he heard one. He’d certainly made enough of them in his lifetime. The Archbishop was alluding to an Interdict.

“I’ll take your confession personally, this Sunday, at Christ Church, Friar Hugh; and we’ll get to the bottom of this. Reflect carefully on your sins.”

Friar Hugh turned white as a sheet. Anyone in Christendom would recognize that as a threat. “Yes, My Lord,” he wheezed. Other than the wicked woman on the stairs, and the Baron, both of whom seemed to enjoy watching the prelate torture his priest almost as much as Andrew himself did, everyone in the room—even the drunken slut hanging on the Baron’s spare arm—cringed and tried hard to not be paying any attention as he verbally lashed his man.

“YOUNG ROLAND!” The Baron roared after sighing resignedly.

“Yes, My Lord?” his son called from the second floor.

“Take our share of the booty we stripped off the Irish yesterday and put it in the Archbishop’s carriage!”

“Aw!” Young Roland whined before remembering everyone downstairs, not just his father, was listening. “Yes, My Lord!” But he couldn’t help himself: “But the trophies, My Lord—can we–?”

Frowning incredulously, this turned his father’s head as even the rude whore on the stairs had failed to do. “He won’t be wanting the sarding heads, will he?!” Turning back towards the Archbishop with the full weight of his eyes, he glowered and concluded: “He’s only here for the shitting Irish gold!”

Lord Dublin held Lord Wrathdown’s glare, letting him see the same twinkling amusement in his eyes the Baron displayed when other people were being hurt and degraded in front of him; but not letting it reach his mouth or any other part of his face or posture. He wasn’t stupid.

“That’s a good start, thank you, My Lord,” Andrew said finally, and formally, giving him his due.

“And we’ll ask Father Hugh to take offerings more often. At least once a quarter,” the Baron suggested resentfully, as the temptress on the stairs made room (but not too much room) for Young Roland and his soldiers bringing down their Lord’s booty.

“God bless you, my son. I understand you and your good Englishmen slaughtered a sounder of wild Irish swine yesterday!” The Archbishop said, raising his voice to elicit the cheer he expected, and got, from the men coming down the stairs. “Good work! I know every soul in Dublin thanks you and your loyal retainers, Lord Wrathdown. But killing can be a heavy burden on the soul. Brother Hugh will stay to take the confession of everyone at the castle after we leave, so no soul feels that weight on them in the morning.”

“Thank you, My Lord,” everyone from the castle intoned.

“Oh, won’t you stay the night with us, My Lord?” The Baron asked, deliberately being an ass. “Our castle is always open to men of the cloth. What’s ours, is yours, isn’t it?”

“Thank you but that won’t be necessary, my son. My Palace is much more comfortable. Its fancy luxuries are well worth an evening ride on Irish roads.”

“We’ll pray for you father, that the damned Irish don’t come out of the dark like the brigands they are and take back their gold.” No one in the room could misunderstand the Baron’s real wish; but no one imagined for a moment he would go alerting the O’Byrnes or the O’Tooles, either. The Baron’s hatreds were as well-ordered as they were cultivated.

“Thank you, my son. With your generous donation, we will provide your son with the best education in Ireland. Tough as you like, mind you, but an education to train him for any position in the Church he may be called to fill. We had wondered…” he began, a sudden motion from the staircase attracting his attention to the woman who, in turn, was now looking intently down upon him without irony. With a mental shudder he couldn’t quite categorize, and a sudden hiccup that made it hard to breathe for a second, it hit him that the siren on the stairs was none other than the boy’s tutor. She looked nothing like her sister, the new Lady Wrathdown; but then, she may have had a different father. By the standards of this place, this room, he supposed, he shouldn’t judge her too harshly: She was, apparently, the most-chaste woman in the castle without gray hair. But the standards of this place were significantly lower than what would be expected of her in Dublin.

Whatever the case ultimately proved to be, there was no time for him to pause and consider whether to change course now; the church would have to make sure later that her appearance here was a matter of her circumstances, rather than her character. Or lack thereof. So he plunged ahead, even as he stepped aside to make way for the men carrying what was now his, or rather the church’s, Irish gold: “Whether it wouldn’t make sense for the boy’s previous tutor to accompany him and continue his lessons?” In his peripheral vision, he saw Lady Parnell trying to nod as emphatically and urgently as she could at her daughter, without making a spectacle of herself; even as her daughter, on the stairs, shook her head with, if anything, greater vehemence. Interesting. It Avoiding attention was a feat she accomplished only to the extent she got her daughter’s attention without causing anybody else in the room to comment. But it went on long enough—uncomfortably long—that anyone with a wit caught it. Lady Parnell shrugged, indicating there was no choice in the matter, and kept nodding her head, expressing her displeasure with her daughter’s defiance with her expression.

Her mother’s face screwed up into an expression harder and harsher than any of the Archbishop’s party—strangers here—might have expected. Something fierce and determined, as she launched herself forward. “You’ve no choice!’

Her daughter jumped to her feet as if scalded and erupted: “You can’t!” She was shaking her head. “You can’t send me there! Are you mad?! I belong HERE!” And then, perhaps realizing that made it sound like she meant Shanganagh Castle, she screamed at the top of her lungs: “ I’M. A. MARCHER!” But her mother was still advancing on her, looking now a dangerous combination of not only rage and frustration, but embarrassment; and as she reached the lowest stair, the daughter yielded and yelped, jumping to her feet: “Please! I’ll do it but—I’LL GO!” She promised, hurrying up the stairs to keep a physical distance from her mother, obviously terrified of the woman, something even little Char, in the care of both of them for six months, had never seen before, either that side to her relationship, or what a terror and a force the seemingly-conventional grandmother could become. “I’m getting packed! PLEASE!” Practically tripping over herself in her haste up the stairs.

Char didn’t understand and didn’t like whatever was happening. Of his new stepfamily, Miss Sindonie was the only one who made him feel safe; practically the only adult in his entire world, after the loss of his mother, who helped soothe his pain and could make him remember what he used to feel like. He was instinctively on Sindonie’s side, and yet the thing he wanted more than anything, the very second he understood what Lady Parnell intended, was what she wanted. On some level, he understood there was more going on here than how she felt about Char. But that didn’t change how Char felt, or what his little heart wanted.

Even the Archbishop felt a second’s involuntary sympathy for the girl, staring daggers at her mother even as she fled her in obvious fear, the very definition of conflict. But the instant she capitulated, it produced yet another complication, tearing another emotional and social rift torn in the room, requiring the Archbishop’s attention:

“GOD’S VENGEANCE!” Baron Wrathdown erupted. “THAT WAPENWIFSTER’S THE WHOLE SARDING SHITTING SOURCE OF THE TROUBLE!!!”

Giggling—a sound closer to spite and the discharge of nervous energy more than amusement—just as her legs and feet disappeared at the top of the stairs, Sindonie promised her mother, she continuing as if she hadn’t just been interrupted: “I’ll get dressed and pack.” And what Archbishop Andrew interpreted as an effort to keep her mother downstairs because she was afraid of what she’d do once they were in private upstairs: “I promise! It should take all of five minutes.” Reluctantly, with a fearful glance at her mother, she paused, stuck her head back down below the ceiling level, and barked at young Charles: “Char-gi” and then, censoring herself: “Go find Oliver! You know where he likes to go!”“Yes, Mistress!” Char practically bounced out of the room, sounding happy, and Sindonie disappeared, leaving the Archbishop to deal with the big fat problem of the Baron’s incredulous, explosive rage.

Looking at the Baron’s tight mask of hate, the Archbishop knew a change in tactics was necessary. Surprising the Baron—and everyone, perhaps even himself—he stepped close and angled his head up to whisper; and the Baron, instinctively, bent down to listen before he could think his way out of doing so.

“If she’s really the source of the problem, perhaps we could persuade someone else who knows the boy…? His grandmother?”

“It’s all the women,” the Baron confessed in a growl, a low sound so emotionless it was scarier than any of the bluster he’d belted out before. “Each one of them’s as vile as the next.”

“Amen,” Andrew agreed decisively. “Then I suggest we take her. Younger than her mother; easier for us to control.” The Baron snorted at that suggestion. “It’ll be for the best, you’ll see. You want your son to prosper and succeed. And he will.” The Archbishop paused and licked his lips, before deciding to finish his thought, a barely-audible hiss in the Baron’s ear: “And don’t forget, all your natural children are at the orphanage, and they’re older. They’re going to hate his guts. I was going to keep him entirely separate from them, but if you want him to suffer….”

“Aye.” And the emotion the Baron packed into that one quiet syllable sent a chill down Andrew’s spine.

“Then he’ll suffer,” the prelate assured the father, before stepping back and returning to a normal voice: “It’s good for the soul.”

“It surely is,” the Baron agreed, and the two of them nodded, bonded by their secret pact. The Archbishop even dared to hope it would make the Baron easier to work with in the future.

The first test of that idea came immediately, as the Archbishop, noticing the fading sun, observed: “It’s time for Nones. Brother Paul—”

But he was already scurrying out the door for the Archbishop’s breviary with a “Yes, my Lord!”

After leading the rest of them in Sext, Andrew took his leave formally, separating from the Skremen women to allow them a more-emotional parting.

Friar Paul muttered to him as they approached the carriage: “This place looks so simple on the outside. But on the inside….”

Andrew shook his head, agreeing with his confidante. When he’d been in Italy, on the way to Rome, he had met Niccolò Machiavelli, a senior official of the Florentine Republic, and read a short book he had written, a more chillingly cold essay on politics than he had ever hoped or imagined to read. He wished he could share the reference with Brother Paul; but as educated as Paul was, he would not have understood it because Niccolò had never published his book, and didn’t appear likely to get around to it! Instead, Andrew answered: “They make Vatican politics look simple.”

Between the relatively significant cache of gold coins, jewelry, fine porcelain, rich fabrics, and other spoils of war from Baron Wrathdown; the relatively small trunk of personal belongings Friar Hugh helped the boy’s tutor carry out of the castle; and the addition of Sindonie and her son Oliver in place of Friar Hugh, there wasn’t going to be enough room in the coach for everything and everyone. He was happy to have the driver tie down Sindonie’s trunk on the roof, but there was no way he going to leave the gold up there. In addition to acting like a beacon for the bad intent of anyone who spotted them on the road, there would be the problem of items flying out since the stuff was still in whatever the men had found to hand when they collected it, including buckets and bundles bound with very insecure-looking heavy twine.

That meant someone…. As Char returned with Oliver, the Archbishop grinned at the boys winningly and asked: “Who wants to ride on the roof?”

Char and Oliver exchanged an excited look and clamored: “We do! We do!”

“Hold on tight!” he encouraged them as the driver boosted them up onto the roof, wondering for a moment what the chance was of them making it to Dublin without mishap. Then, shrugging and seeing Father Hugh standing awkwardly beside him, he forgot about the boys on the carriage top: “Go on, your flock are waiting for their confessions.” And without pause or inflection betraying his complex feelings, he said naturally: “And have a nice walk back to Dublin, son,” only his closing comment distilling the truth: “I’ll take yours on Sunday. I’d recommend you be there at noon sharp.” He didn’t need to explain the importance of not being a straggler; the line would be very, very long. It always was, when the Archbishop came into town. And with that, he stepped into the carriage and, by force of will, squeezed in next to Friar Paul instead of tempting fate by sitting across from him.

The copper-topped boy slipped silently into the empty bench opposite them, shrinking instinctively into his corner as Sindonie sat next to him, her posture as easy and comfortable as his was tight. With a sympathetic look, she put her arm around him and pulled him against her hip, petting him reassuringly. “You’ve had a terrible few days, haven’t you, love?” Sindonie was such a sexual creature with men, her transformation into a sweet nurturing role with children was as startling to Andrew and Paul, as it was natural to her. In an instant, they could see how she, rather than one of the other women in the castle, had wound up being chosen as Char’s tutor. In addition to being good with children, she was obviously smart. But when they heard the Baron’s angry voice rising again, just before Lady Parnell slammed the castle door shut, the three adults in the carriage exchanged glances and the flery flash of her eyes was enough to unsettle both of the churchmen sitting across from her.

As a hint of a smile played around her lips, obviously enjoying the effect she had on men, she turned her attention back to the child beside her, stroking his hair and, against all odds, beginning to start the process of helping the boy relax for the first time since any of them had met him. The Archbishop hadn’t even realized how tightly wired he was, until she began gentling him.

As the carriage began moving, their four guards clopping along on the backs of their horses behind it, she cooed: “You are the smart one, aren’t you? Poor Oliver and Char are so excited now. Silly boys. So cute. But they’ll be wishing they’d kept their mouths shut soon enough, hmm? Maybe you could help my little Oliver learn when you’re helping Char?” And when he remained quiet, she encouraged him: “What do you say to that?”

He looked at her with his serious face and said: “It’s not Irish.”

“What, dear?” she blinked, speaking for all the confused adults.

“It’s ours.”

“What is?”

“The treasure.” The three adults shuddered in the same instant, sharing a look of dismay, realizing as soon as they heard the two words, the boy had to be right. Confirming what they had just intuited, he explained: “They may have taken it from the Irish. But the Irish didn’t bring it with them.” Of course they hadn’t. Raiders didn’t come laden with booty to distribute to their victims; they took it away and tried to leave with it.

The boy reached forward and carefully picked out two gold pins in the shape of matching harps from the bucket. Before he even got to it, the adults all felt the sinking certainty that the boy’s reflection was going to be a punch in the guts. “They took it from us. These are the badges of Raheen-a-Cluig.” Meeting the Archbishop’s eyes, he elaborated: “They belong to the Lord and Lady of Raheen-a-Cluig Manor.” He knew the stolen treasure by sight, Raheen-a-Cluig’s last witness. The fact he was talking about his own murdered parents made his wooden—no, his dead—intonation all the harder to bear.

Finally, softly, almost—but not quite—allowing himself to touch his memories, something close to breaking in his voice he squeaked: “They liked to match. Everyone agreed they were the cutest couple on the mountain.”

“Oh, my sweet little boy,” Sindonie moaned sympathetically, tearing up even as she pulled him gently back into her warm embrace. “My sweet, sweet boy.”

Watching them, before the Archbishop’s brain could stop itself, it released a traitorous thought:

The Holy Mother Church thanks you for your generous donations.

That thought had come too quickly for him to prevent. As did its corollary: Whether voluntary or posthumous.

Makes no difference to us, he almost chided himself, but refused to entertain the next thought, which he knew would have been whether the heir and only survivor of Raheen-a-Cluig didn’t have a better claim on this treasure than Baron Wrathdown, and thus the Church itself?

Speaking emotionally, Sindonie asked: “I’m sorry, child, but when you visited us before I was so focused on what was happening to little Char, and I didn’t know you yet…. What’s your name?”

“Pen,” he answered, his voice nearly breaking, and Sindonie wept, holding him with such tender fierceness his own tight rein on himself eased just enough for him to break down into the grieving he needed to do.

“Pendragon Argent. The little lost Lord of Raheen-a-Cluig,” the Archbishop blurted, surprising himself with his own unexpected sentimentality, half an inch from imitating them and bawling. Hearing the catch in his own voice, he decided it was probably too dark to ask Brother Paul to take any more dictation. And so the two men sat in silence a long time, while Sindonie petted and hugged the weeping child in her warm, caring arms; preoccupied, to judge by the scene at Shanganagh, by her own cares, if the child’s were not enough for both of them.

Literature Section “08-02.5 Complicated House of Horrors”—more material available at TheRemainderman.com—Part 2.5 of Chapter Eight, “The Wild, Wild West”—7828 words—Accompanying Images: 4580-4584—Published 2026-01-11—©2025 The Remainderman. This is a work of fiction, not a book of suggestions. It’s filled with fantasies, stupid choices, evil, harm, danger, death, mythical creatures, idiots, and criminals. Don’t try, believe, or imitate them or any of it.