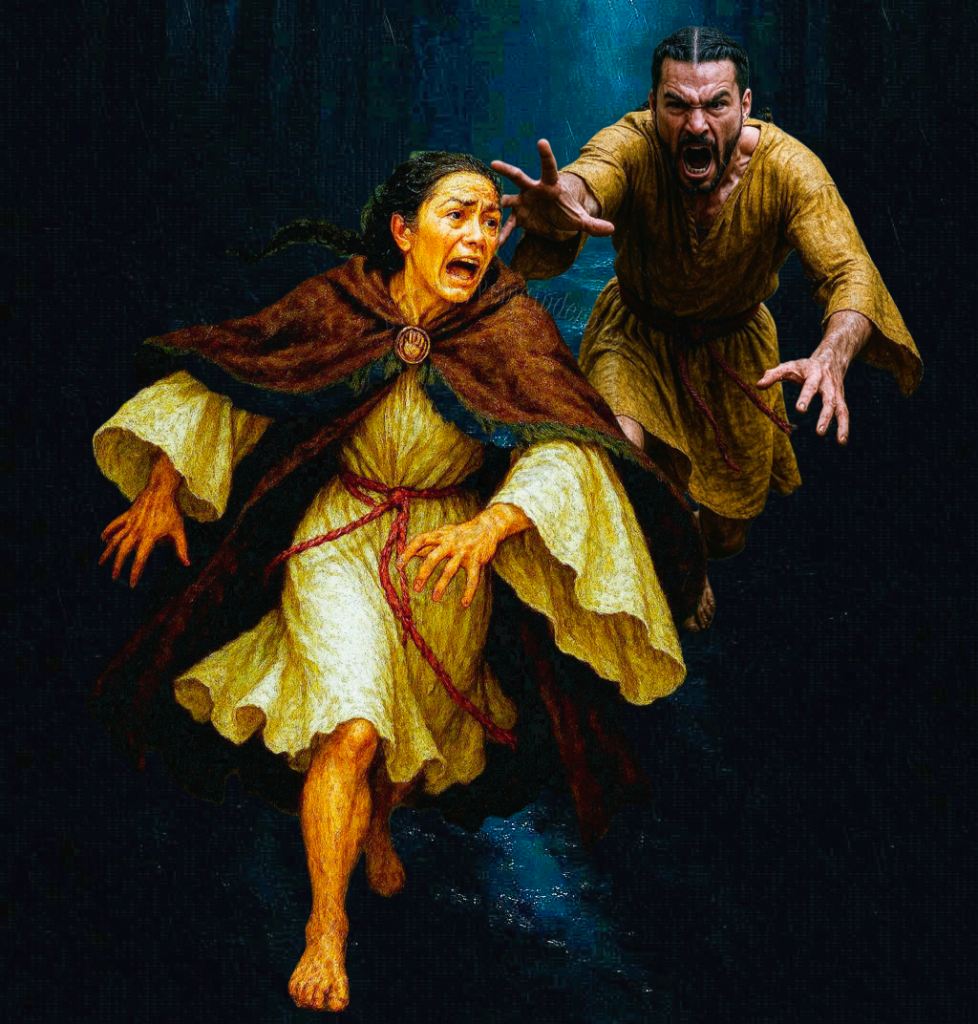

4651 08-0.5 RUN!!! (Cacht’s final seconds)

4660 08-0.5 RUN!!!–ALT better expression but less historically authentic

CAUTION: Contains themes of violence and injury some readers may find disturbing.

If this account is suspended, go to theremainderman.com or search for a new DA account with “Remainderman” in the title.

GLOSSARY: Cill Mhantáin—Wicklow; Éire Ghaelach—Gaelic Ireland.; Uí Broin—O’Byrne; Uí Tuathail—O’Toole; Sacsanach—Saxons; English; Normans

Éire Ghaelach. Another country—another world, from Dublin. Her world.

Her whole world—the men of her cland—were howling and shouting behind her.

Coming for her.

Coming to tear her apart.

The Petition of the High Queen: She heard the verse forming like a background noise in her head, like a waking dream; something that had its source outside her intention. The verse written, because it was not to be spoken. As rare as a Bible, in an ancient culture of oral tradition where language was king but writing foreign. A language only written by priests and Sacsenacha, in their scripts. Rarer still, a written secret belonging to women. Their own secret legend.

“Desecrator!” “Cursed bitch!” The angry cries of men—men she’d grown up with; men she’d trusted.

Her own people. Sounding closer.

She pushed herself even harder, until her lungs burned and her bare feet ached in the cold mud and bruised by the sharp edges of stones and sticks on the dark forest floor. The rain poured down around her like mad, and the night sky was pitch black except when lightning crackled across the sky. In the dark moments, in the thick trees, branches slapped and tore at her arms and sides and, despite her efforts to protect it, her face. Her leine and brat (chemise and cloak), all she had in the world now, were plastered to her skin with sweat and rain.

“CACHT!”—an agonized, furious cry, the one that hurt the most: her own father. This was her name day. Her coming-of-age day. She hadn’t thought—when it happened, when she was crushed, she hadn’t imagined—

In a flash of panic, she couldn’t breathe for a second. And when she resumed, the pain in her chest had become like a brand, a searing point of heat.

And then she heard words even scarier than, if not as brutally painful as, her father’s: “There! I can see her!”

“This way!”

“We’ve got her!”

“Devil-whore!” one of the men screamed, his voice cracking. Sounding close—too close.

But it was his curse that put the mad idea squarely into her head. Or maybe, it was only what made it consciously thinkable; raising it to a thought from a dream. A thought that worried at her for her attention, as if she had the attention to give it!

Her mind was racing faster than her body: fear, grief, desperation, electrifying and worrying at her at exactly the time when she needed distraction the least! Where was she to go? What hope did she have?! She didn’t even have a plan. And there was a reason for that:

She had nowhere to go. Nowhere she could possibly reach. The truth slapped her face more remorselessly than the oaks, the ash, and the rowan.

Their village of Achadh Mheánach was deep, deep in the heart of the lands of the Gabhal Raghnaill; leaving the lands of her fine was more a matter of days than hours. And if she should—what then? To the East: more Uí Broin. More distant kin, but still kin. They wouldn’t protect her; they’d turn her over. To West and South—the scourge of their land: Sacsanach scum. That left North, the Uí Tuathail, no one she wanted to deal with either, only conceivable because none of her other options were.

She wasn’t even serious about the idea when it—no, that wasn’t quite true: It wasn’t just an idea. It was an idea accompanied by an intention: a wish, really; was that enough? Something told her it wasn’t, but all the same, the wish began running through her mind, in rapid fire, over and over and over again:

A Bhanríon neamhnaofa na hÉireann a bhí trí thine

Mise, Banríon na hÉireann básmhaire, impím ort

Glaoim ar do ghealltanas! Glaofaidh mé ort Máistir!

5026 and…

She calculated it in her head, an outrageous indulgence of time and thought under the—464! Was she sure? 464!

5026 and 464. Mallacht ar m’ainm.

Mise, Cacht iníon Ragnaill. Is leatsa mé!

She didn’t even realize where she was heading until she was almost there. Running, yes, but she had been running from, not to, anything.

And then she realized where she was. The rest of her life to wonder whether it was her own will, or fate, or some darker agency that had brought together place and time and circumstance and solution, sealed with a snap:

Behind her, the sharp crack of a limb, solid enough to remain dry enough in its core to break; slender enough to be broken by the bare foot of a charging man; and his curse as he stumbled. She knew the voice well. Too well: Her bastard usurping cousin Brádach, he who had already conspired with her own father to take everything from her. Everything! No, not simply to take—to make her, and her life, into nothing! Of course he was the closest. He would do anything to destroy, or even wound, her; her very existence a threat and offense to him. The tears stinging her eyes were as bitter as the bile in her mouth.

So close!

The sound of him shuddered for a moment as he struggled to keep his feet and ignore the pain. But when he pulled through it—the instant his feet, less than a fertach behind her, recovered their rhythm, she knew she was done.

They had her! She heard the laughter in her own voice, the forlorn hopelessness of it, as she panted it out, wasting breath she needed more of than she had:

“A Bhanríon neamhnaofa na hÉireann a bhí trí thine

Mise, Banríon na hÉireann básmhaire, impím ort

Glaoim ar do ghealltanas! Glaofaidh mé ort Máistir!

5026 and 464. Mallacht ar m’ainm.

Mise, Cacht iníon Ragnaill. Is leatsa mé!”

Could she really feel the man’s breath on the back of her neck as she started repeating it, now a mantra she preferred thinking about, than facing the fate about to ruin her: “A Bhanríon neamhnaofa na hÉireann—“

That’s enough. Not her voice. Was it? Now her laugh was hopeless: she had gone mad, a mercy given the fate that awaited her. Mad you are, but not for hearing me: for calling me.

“Yes, I’m mad!” she shouted—sobbed, more like. Obviously! And then she wondered: Could she kill herself, before they—

Too late for that. You’re already mine, and I don’t waste what’s mine.

You will by talking! She thew her thought back against the madness working in her head. They have me! My plea is urgent!

Wry laughter: It usually is. To call on me? Not many ever make a plan of that. But I move through time by my own paths, crawfishing around the clock as I please.

Craw—what?! I don’t care! “Save me!” she wailed, reduced for a moment to nothing more than her own terror.

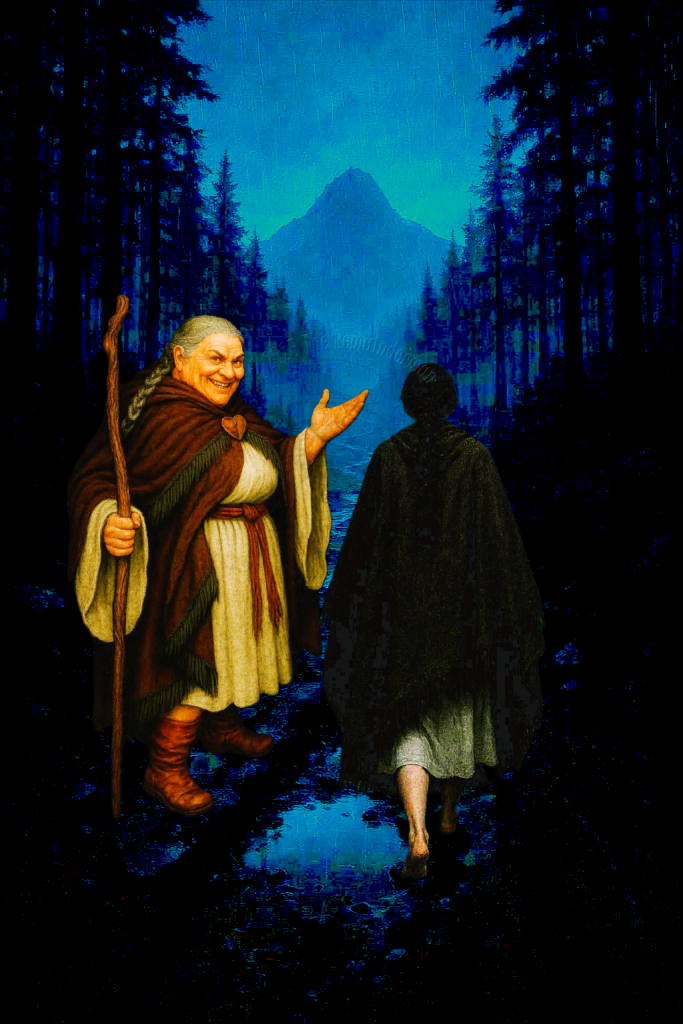

More laughter, only it wasn’t in her head any more, it was in her ears, over the drum of the rain: “If you wanted salvation, you should have called on another. But you called on me. Now: Close your eyes!”

And there she was.

There, in the place of the old stones, called the circle of Gleann Abhainn Ow, right in the middle, standing on the ancient altar stone. The ancient sacrifice stone.

“Close. Your. Eyes.”

Cacht stopped short and did so, hit and tumbled a second later by Brádach, who seized her, surprised but not deterred by the sudden end to her flight.

“Giving up!” He spat it, like an accusation. “Of course!”

“Yes, but not to you. Hands off!” The woman commanded.

And with a flick of her wrist, Brádach reeled back, letting go of Cacht with a surprised grunt. A second later, as cracking branches and gasping breaths announced the arrival of her other kinfolk all around them, still unaware they had been joined by an outsider, Brádach cursed: “What’d you say, witch?!” as he formed his fingers into a ball, swinging forward again to break her jaw.

Two things happened, at once: First, Brádach, his knuckles reaching a faint purple glow that had sprung up around Cacht, screamed and fell to the ground in agony, as every bone in his hand and forearm splintered into sharp pins of bone, giving Cacht a feeling that was twice as poignant for being so complex: combining relief, empathy, horror, and yes, to her shame, even schadenfreude. Second, a mighty strike of lightning, closer and fiercer than anything any of them had ever seen or imagined, came down on and around the altar stone, turning the night to day and revealing all, so that none might be mistaken any more:

Gleann Abhainn Ow, a fresh and green valley that Odysseus himself would have recognized as the Elysium Fields on a sunny morning; now dark and lashed by a fierce rainstorm that had rolled over the vale from the West. Ancient trees of Ireland’s primordial forests, one of the few original woodlands left to show them what their ancestors sang of. The glint and motion of the water of the Ow, tumbling and pouring over rocks, overflowing its banks and reaching longingly for the comfort of the mysterious stones.

The stones: Ancient things, gray and massive; carved with cryptic Celtic knots and oghams older than any living memory or ancient song could explain, a small circle of big stones around the altar. The grove was a calm in the storm. Heedless of men and time. Haunting and beautiful here, where they had so long belonged.

And in the middle of it all: Her. The hag herself.

“Cailleach!” Ciardha, her father and leader of their village, named her. In that long, lingering magical moment, everyone but Cacht registered her presence and identity, in the second before the inferno of the lightning strike burned their eyes to charred bits of meat. Nearly a quarter of the Gabhal Raghnaill’s fighters crippled in a flash, a mighty blow sufficient to put her entire fine’s liberty and lives in jeopardy for a generation, shrugged off as easily as a brat.

Cacht screamed in horror at the felling of her family—the adult male fraction of it, anyway—permanently rendered from proud hunters to vulnerable prey; from a pillar and strength of their seed, to a liability that would burden their overwhelmed widows and children for the rest of their short lives. “I didn’t want this!”

“But you caused it.”

Cacht sobbed and wept, shaking her head in disbelief. “No. It’s a dream—a—“

“It’s no dream,” the Cailleach assured her cruelly. “It’s what you willed—or made inevitable. What you dared. To summon me?! And under false pretenses? That verse was not given to you or made for you. It was gifted to Cacht ingen Ragnaill almost 464 years ago.”

“Cacht! What have you done?!” her father’s voice cried, the agony and heartbreak in it, the reminder of love worst of all, tearing her apart, making her bleed her grief like a cistern overwhelming the dam built to contain it.

“I—there was nothing false!” she wept in protest, not even sure if that was what mattered. Perhaps she was seizing on the only thing she could, the only untrue piece of the narrative that she could hang onto for her life, and deny the reality of all of it; or at least, any part of hers in bringing it about.

But her new master was cruel; and would not suffer her to keep any illusions of it: “You aren’t Cacht ingen Ragnaill. Although, before you go experiencing any useless hope, be clear: having taken it voluntarily, and used it for magical advantage, it will and does bind you as surely as your own.”

“I am Cacht ! Cacht of the Gabhal Raghnaill!”

The old hag clapped her hands and cackled in delight. “Clever girl! Thinking on your feet and fighting for yourself in the midst of the ruin you have wrought on all you held dear! You will be useful to us!”

“It’s true!” Cacht wept, falling to her knees, clinging to this little bit of certainty, this narrow island of defensibility separating her from the awful field of consequences around her.

“It’s not,” the old woman laughed harder. “That Cacht is long dead. I know, because she’s still and always will remain under my thumb, suffering for me, in hell.”

Cacht moaned in horror as the woman confirmed that which she had most-feared, that she did indeed understand what was happening here. But the woman wasn’t done explaining how she had spoken falsely: “Nor are you 500 years old. And you are… ha ha, no less than the fifth Gaelic stria bréagach liteartha—“ Cacht barely had the energy or bandwidth to register the insult, but still burned like a coal being forced down her throat, demanding her attention, knowing her kinsmen would remember it. Lying literate whore, or something like it. “—to call on me with that verse. It was supposed to be for her only. I couldn’t believe it when I learned she’d written it down and passed it on. Well,” she laughed. “That’s what happens when priests come bearing Latin and Christianity, to ruin a perfectly-good and I would have said, defiantly oral culture. But it’s worked out well for me!”

Suddenly her expression changed, and then her entire countenance changed, right in front of Cacht, into something Cacht had never seen or heard told of. Something reddish-orange, horned, and fanged but barely-dressed in scraps of fabric that would make a prostitute blush. She became nothing less than the whore of Babylon herself, decadent and wanton in a way the Book of Revelation could not have prepared anyone for. Cacht screamed and gasped at the same time, a ragged, torn, shocked sound that struck more fear into her moaning kinsmen, kneeling and clawing at their eyes around them, wondering what was happening now.

So, she was already screaming when the Cailleach leaped forward, further than Cacht would have expected the greatest warrior among the Uí Broin to do, landing even as she was swinging the heavy wooden walking stick that had materialized in her hands sometime between her initial appearance here and when her blow landed on her cousin Brádach’s head, knocking him out and nearly cracking it open.

“You killed him!” Cacht screamed, horrified, immediately echoed by the mournful cries of her blinded male relatives. Even as her eyes fell on the explanation for the hag’s sudden violence, and sad understanding wilted anything good in her eyes. Her cousin, blinded and with one arm ruined, had pulled his knife with his remaining good hand; and, too consumed with rage and hatred toward her to be thinking about himself or his clan—or even how Ciardha would have felt about it—had been intent with every bit of his focus and consciousness on stabbing Cacht in the back. Not the future; not healing or even surviving. Simply lashing out and hurting.

Cacht threw up, the Cailleach—if that was even what she was—carefully keeping her distance, to remain unsullied, at least by physical matter. “Oh, no. That would be too easy. For all of you lot,” she spat, in case any of them imagined themselves forgotten by her, or immune from her sadism. “His own kin—your kin—will have to kill him, if they don’t want his broken body to haunt and burden them the rest of their days.” She snorted with pleasure at how much her words upset the humans around her, every one of them, even Cacht. “I don’t know what you’re so upset about,” she lied. “These bastards were going to—well, I can’t even imagine the fate they had in store for you.” Another lie, or near to it. Her imagination was both savage and inspired; and her experience in human harm and misery, nigh-on unparalleled. “You’re all damaged goods now. What a miserable burden you’ll be, the rest of your lives. What do you think, will your cousins, the remaining Uí Broin, let your wives keep ruining their lives supporting you when they take them for themselves? Or will they put you to death when they kill your whelps?” Delighted with their protests, especially the threats and curses even they didn’t believe would make any difference, she concluded her monologue with a few final nails: “You shouldn’t have gone after this poor little girl, you bastards!”

“She destroyed our cland’s wealth! Our church!”

“I’m sorry!!!” the girl screamed, weeping bitterly.

“What, a bit of kit and a wooden building? No threat of broader fire in rain like this! Doesn’t seem like much damage now, does it? Should have forgiven the girl, shouldn’t you? Now you’re all blind, and your cland effectively destroyed. You armed scum” (and by armed, she simply meant male) “be sure and warn all and sundry who’ll listen to you of the terrible Cailleach. And warn them double, to beware any woman knowing the Petition of the High Queen, for you’re the evidence of how terrible my vengeance against those who cross my women will be!” More lies; words to set man against woman; anything to set person against person, make them need her; make them dependew

“Now… one last bit of business before I go.” She turned to Cacht. “This man Ciardha, he’s the leader of the cland, isn’t he?”

“Yes,” Cacht answered reflexively, numbly, before thinking better.

“And he’s your actual father, isn’t he? That’s why you had the knowledge to call me, Cacht ingen Ciardha?”

The girl’s eyes widened and her stomach hurt as she felt a danger she still couldn’t quite see or imagine, but now suspected was there, opening up like a scar on the world under her feet. “I—I—no, I—”

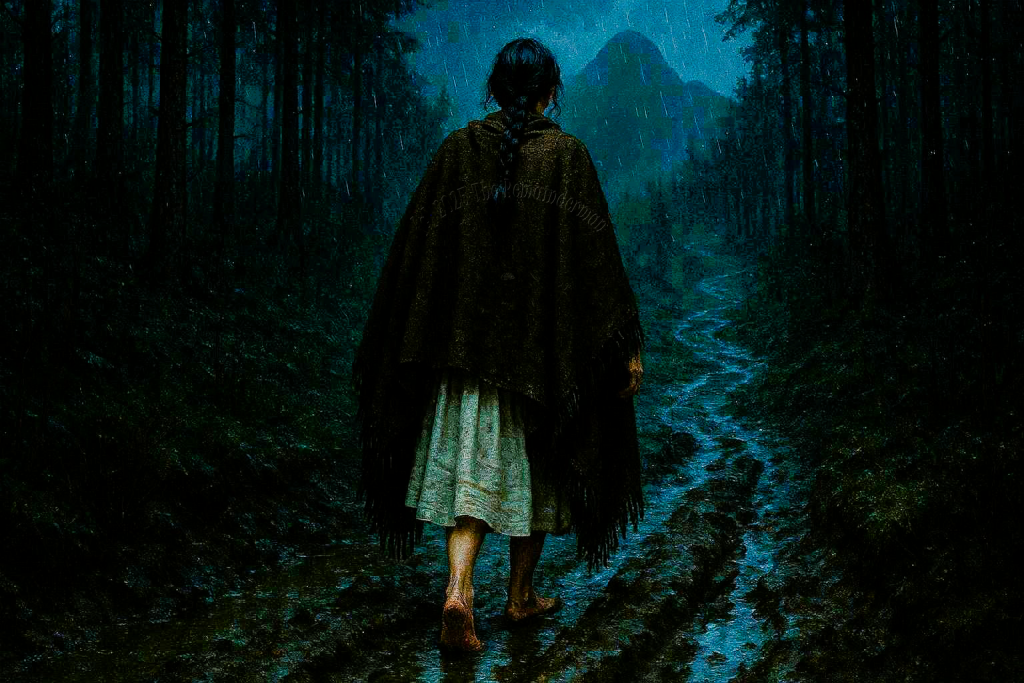

“Liar!” The Cailleach snorted. “But not much of one. Not yet. We’ll have to work on you. Sister Maud Máire!” She called, and Cacht gasped again to see another Cailleach, not quite a twin to what the first had originally appeared to be; but close enough, a suitable hag for the Irish Cailleach, standing not ten feet away. “Show this girl the way. Up to the top of the great mountain.” It was theater; they weren’t going to climb any mountain; but why help people to understand their ways? “You and your sisters, clean her up and dress her for her wedding!”

Cacht keened in dismay, even before the second hag smirked, looking at the devastated Cacht with a twinkle in her eye, demonstrating her own capacity—and indeed, appetite—for cruelty: “Aye, Cailleach. We’ll dress and make her up into a wanton slag-whore, to incite the beast’s lust!”

Cacht and all her conscious relatives made sounds of shock and pain and fear, expressing their complex emotions, the same that had brought them all here and were tearing all of them, their whole fine, to shreds.

But Cacht’s misery and fear were divided, as the last of the humans here who had eyes. The Cailleach had turned, and was walking predatorily toward Ciarcha.

“No. No, what’s happening? Stop!” Cacht tried in vain to escape her escort’s grip, and resist her efforts to pull her toward the stone.

Looking pleased, the Cailleach growled: “If she’s stupid—or weak—enough to stay, all the better. Let her watch! But hold her back if she tries to intervene. I’ve got one last item of business before I go, taking the head off this cland so no one can mistake my leaving these other men as anything other than the warning it is.”

“What are you going to do?” Cacht began. “Stop! Daddy, run!” And then, breaking into tears and screaming as urgently and emphatically as she could, screamed: “RUN!!!”

Her father, already walking backward uncertainly, turned and tried to run away, almost immediately running head-first into a big ash tree, provoking derisive laughter from the hags and another sob of sorrow from Cacht.

“After all this excitement, I’m a bit hungry,” the Cailleach confessed, provoking a new din of screaming and wailing from the panicked, lost, overwhelmed humans around her.

It was said she left his bones scattered all over the circle of stones, following him around as he became less-whole, and definitely less-mobile, as his male relations tried to find them by sound alone. And in that way, the beautiful sacred place became a desecrated, fell pit to be avoided. No one knew if it was what had happened, or the fevered tales of men out of their minds and disoriented, having just been blinded. After all, it could just as well have been the animals that finished him off; none of the survivors were able to see.

Literature Section “08-00.5 The Opposite of Salvation”—more material available at TheRemainderman.com—Part 0.5 of Chapter Eight, “The Wild, Wild West”—3458 words—Accompanying Images: 4651-4663—Published 2026-01-22—©2026 The Remainderman. This is a work of fiction, not a book of suggestions. It’s filled with fantasies, stupid choices, evil, harm, danger, death, mythical creatures, idiots, and criminals. Don’t try, believe, or imitate them or any of it.