Everything began the autumn of the haunting.

Once upon a time, not so very long ago, fortune beamed on the Defalais family with a generous light reserved only for the luckiest. Lord Robert, the Earl of Warwick, was one of the most powerful and prominent men in England, politically astute and well-esteemed by King Henry VIII. Lady Margaret Mordaunt’s grace, charm, and beauty had been celebrated even before her debut at court, and even before tragedy and piety had cleared a path through her six older sisters to her marriage. Her family’s title had gone to her younger half-brother; but she had brought estates of her own to join those of her husband’s. Both families had joined the Tudor pretender at the Battle of Bosworth Field, and been richly rewarded with the plunder despoiled from those who had kept their oath.

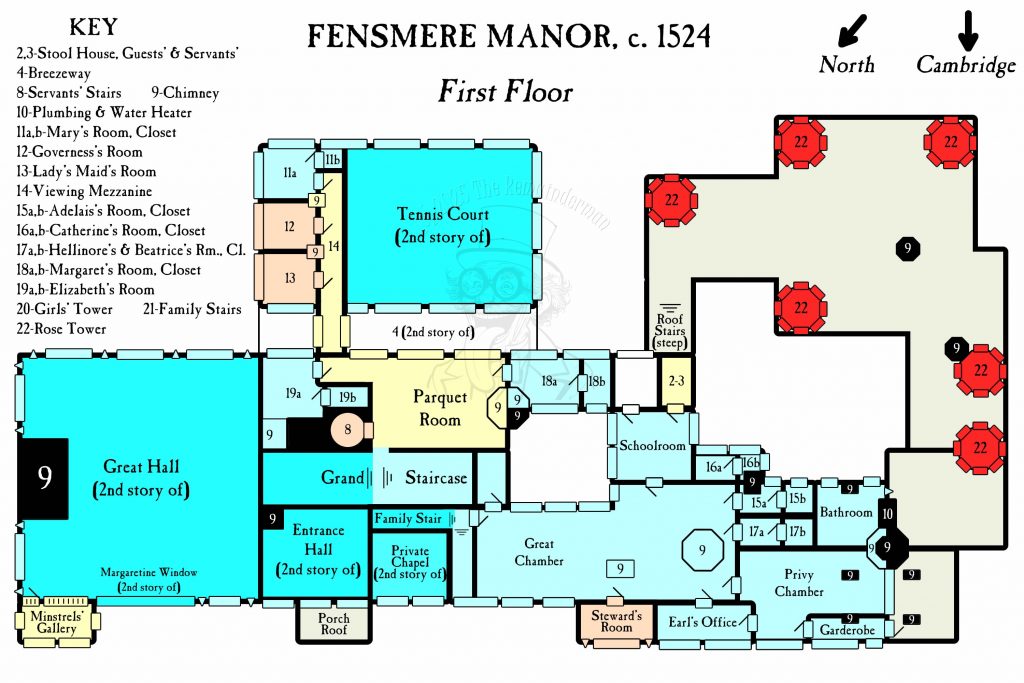

The couple’s courtship had been the talk of the court; their wedding, the event of the season; and their affection manifest, in the form of seven accomplished and (mostly) proper daughters: Margaret, Elizabeth, Mary, Catherine, Adelais, Beatrice, and Hellinore. The eldest were well-wed, the middle children hopeful, and the youngest naïve. They enjoyed the best tutors their mother could arrange from among the faculty of nearby Cambridge University.

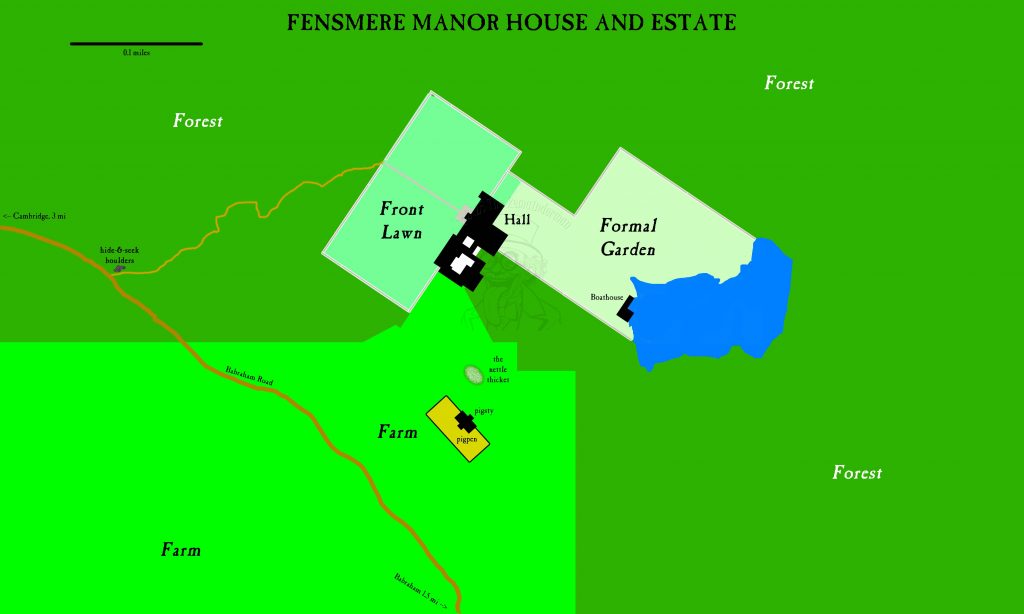

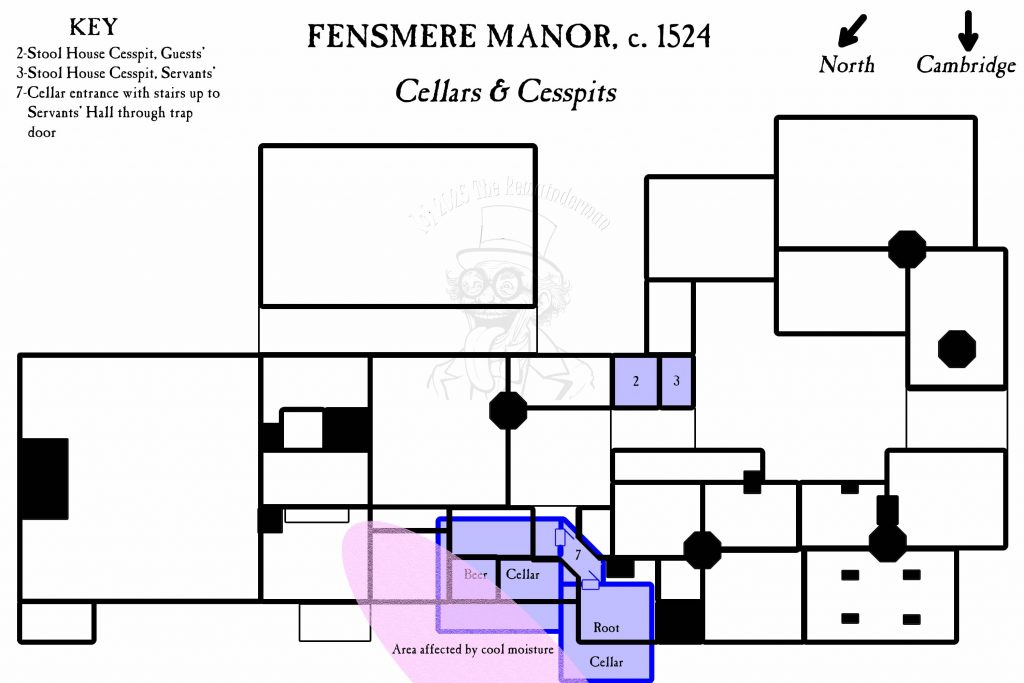

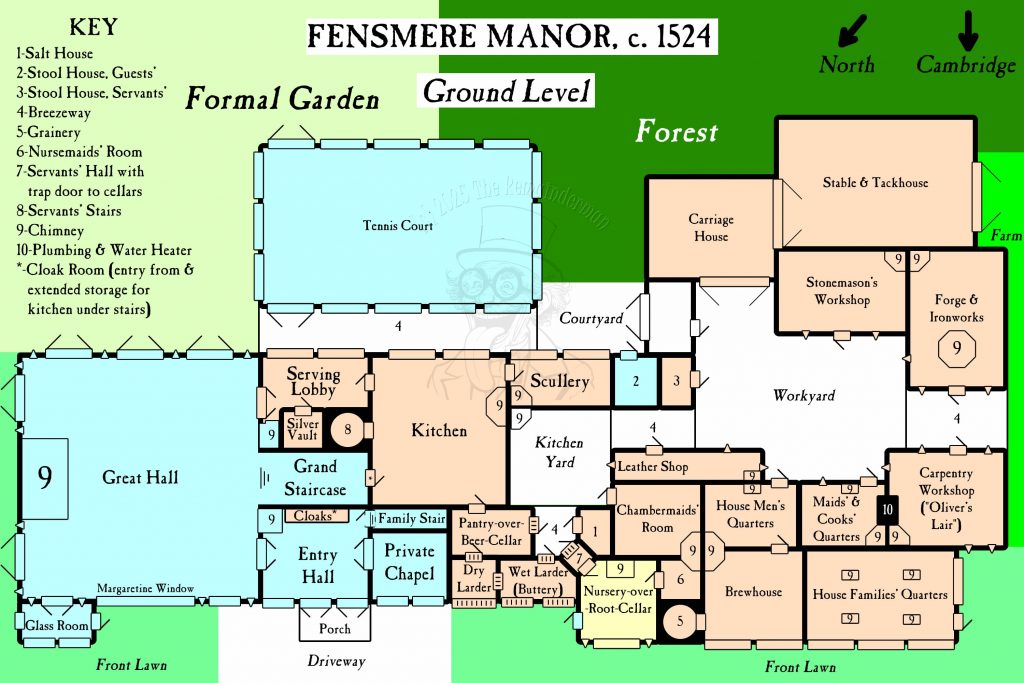

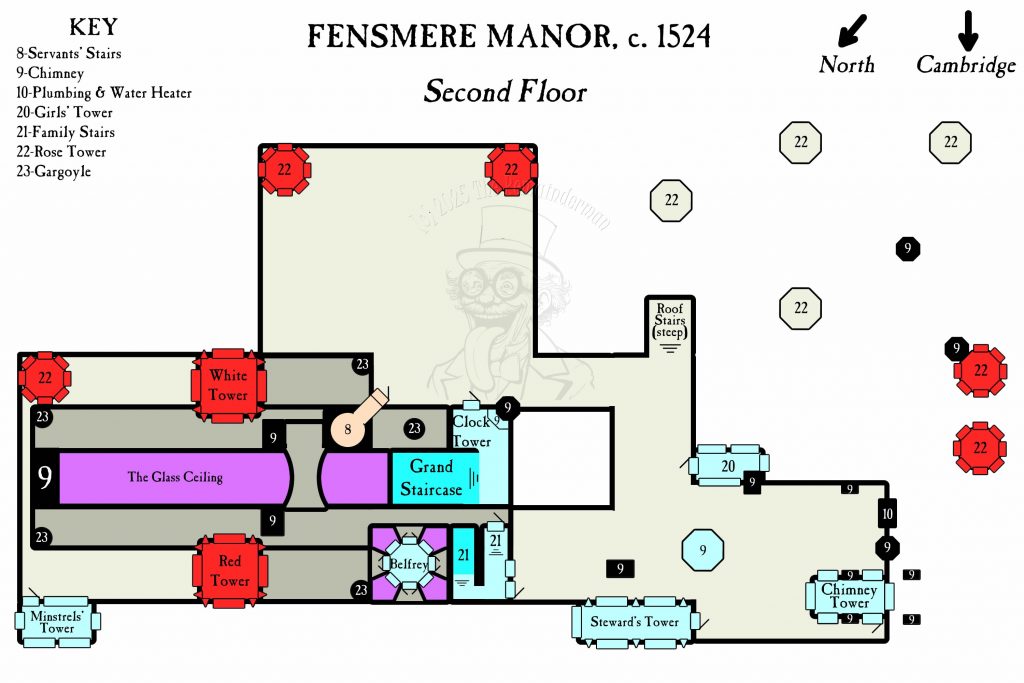

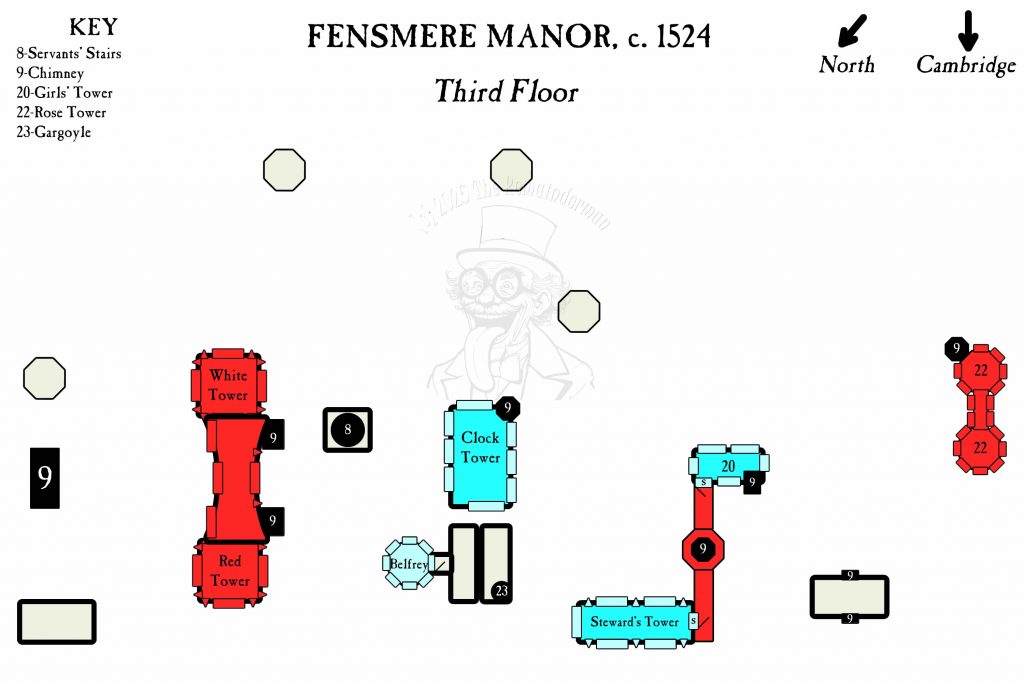

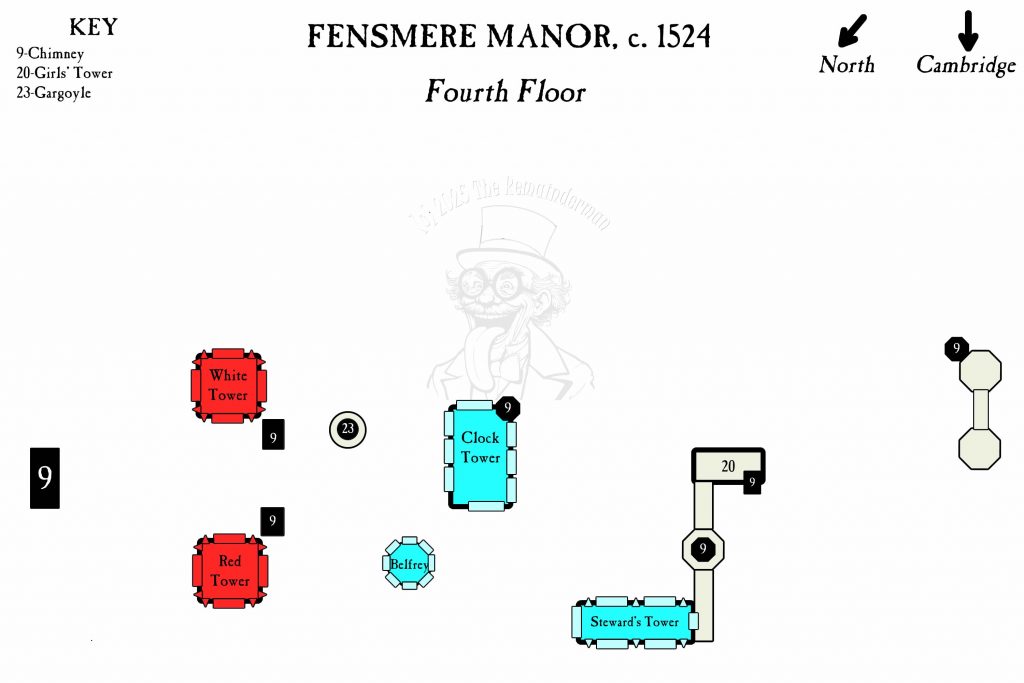

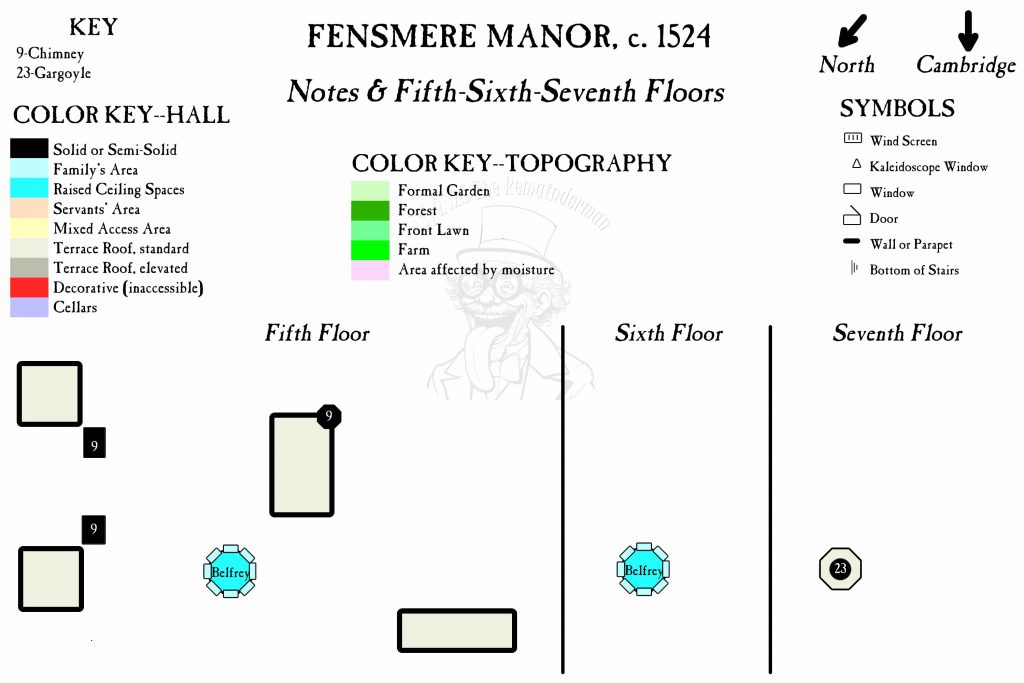

The family dwelt in splendor at Fensmere Manor, a newly-built seat ahead of its time, more luxurious and pleasant country estate, than drafty fortress for hiding in. Blessed with health, wealth, education, position, strength, and even family, which all considered their birthright, their destiny was to blossom and grow, crowding out the needs and ambitions of lesser bloods.

Or so it appeared, until a tragic fall robbed the Countess of her life, the family of its joy, and England of one of its most precious gems. The daughters lost their role model, their most ardent advocate, their fiercest defender, and their loving, attentive mother. The Earl was distraught, distant, and thoughtless in his own grief, practically a second parent lost to them even as he lost his own way, leaving his daughters in the capable but uninspired hands of his servants.

Then SHE appeared: Anne Batonnoir, a Lady of obscure family origins but great charity somewhere far to the West—Devon, Cornwall, or even the Pale. Her brother Jerome was a Herald of Arms in service to the King, and she was well-respected throughout the English clergy as a charitable woman who helped them care for orphans of quality and piety. Jerome had slowly achieved some minor influence at the royal court, and now she quickly achieved even greater influence at the Earl’s.

None could deny her extraordinary beauty, magnetic charisma, or easy self-assurance. Her spirit, body, and manner were indisputable evidence of her gentle birth and high prospects. And men not inclined towards the counsel of their mothers pursued her with as much focus and intensity as their mothers displayed in trying to steer them towards more-eligible, less-interesting women like the Earl’s daughters.

Her first appearance in Cambridgeshire, like Lady Margaret’s final tragedy, coincided with an autumn of ill winds, momentous storms, and inexplicable losses. As the weather grew colder, crops wilted; cattle were mutilated; people disappeared; and rumors spread, of fires spied and chants heard deep in the woods. Of remote dances and orgies on the darkest nights, and unholy ceremonies when the full moon was in zenith. Tales of demons and witchcraft rattled the unsteady and inflamed the superstitious. And some—among them, it must be said, the most jealous and least charitable of women—whispered that Robert’s alacritous courtship of Anne was more than unseemly: it was unnatural.

Still, less-suspicious women, and virtually all men, took one look at Lady Batonnoir and dismissed supernatural explanations. Not that the men were likely to share those thoughts with their wives, but they did with one another.

If Lord Robert’s first wedding was a fairy tale, his second was a delicious scandal; and definitely the subject of as much gossip as his first. Soon after they took their leave of the celebration, the guests near the stairs to the Great Chamber became excited, drawing other guests to them.

From above came the unmistakable sounds of a very passionate woman, being aroused and then, in turn, bitterly disappointed by her groom. Within ten minutes the gentry of the whole county, and those few of their peers from elsewhere who had been able to attend the quick ceremony, learned not only that the new Countess was as expressive and hard-working as she was attractive, but also that the Earl was a quickjack who had already been accommodated twice today by his energetic new wife before their marriage was thirty minutes’ old.

As best the attentive crowd could gather, he had attempted to defile her just before the ceremony, only sparing her wedding dress by ruining his own breeches before he could get them off. Even so, he had just barely and technically managed to consummate the marriage by penetrating her (ineptly and painfully, it seemed) before spending himself. The guests, embarrassed, scattered to report their news to everyone they might come across, carefully avoiding the Earl’s mortified older daughters who were struggling to maintain their dignity in the presence of their father’s vassals.