CAUTION: Contains themes of war kidnapping and bigotry some readers may find disturbing.

No one had told the children about the Irish letters.

They knew something had happened—of course they did. Even the children knew cattle had begun disappearing again, and that this was a sign the Irish were getting restless. Or hungry.

Two weeks earlier, everyone’s breakfast had been interrupted by the sentry, sounding shocked and uncertain at first, then louder and more insistent once he was certain about what the slowly-thinning curtain of the morning twilight was revealing to him. But he didn’t ring the alarm signaling imminent threat, natives spotted. Instead, he went on about the two soldiers who had gone missing on the road a couple of days before, saying they were just outside.

Men had rushed to the roof of Shanganagh Castle at his cries, then come down more slowly, gathered more of their number, and headed outside.

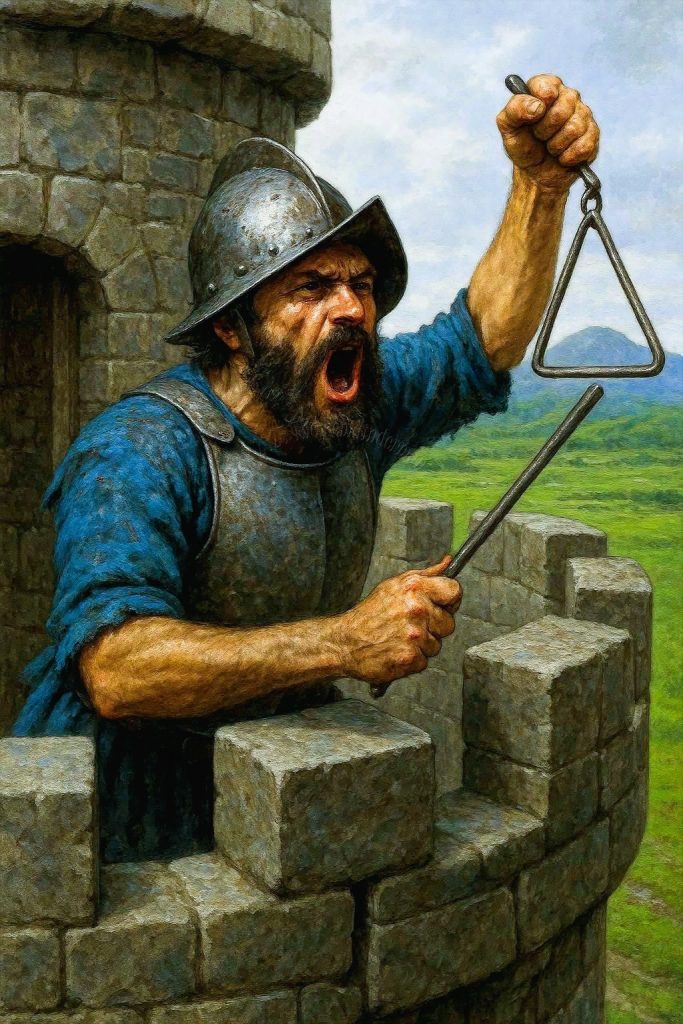

The women and children had been kept inside, on the ground floor where there were no arrow slits to see outside, only the door facing Dublin, away from Ireland, reducing them to speculation. All the men who had gone outside went armed, as best they could be: from the Baron and Char’s older brothers in their fine, well-fitting armor with sharp longswords (no one’s armor was new for long at the frontier; but quality showed even—perhaps especially—in heavily-used equipment), and their similarly-attired knights; to their squires and the militiamen—freedmen of means with their miscellany of polearms, protective shirts, and preferably helmets of metal or at least boiled leather. The Baron even had an arquebus, for three years now, but it remained more of a bragging point than an effective component of his arsenal. He waffled back and forth between considering it a dishonorable weapon, and an impractical one.

The Baron himself had taken charge outside, handling whatever the “letters” were. After one of the soldiers reported breathlessly to Young Roland “They didn’t take the animals!” Char’s brother gloated, either hopefully or encouragingly (depending on how sincerely you took him), that they hadn’t dared get so close to the Castle. He sent men with farm tools, guarded by two of the armed freedmen, to milk the cattle in the barn, which was literally 20 or 30 feet behind the entrance to the castle. The older children were more or less able to put it all together; the younger ones were left with their anxiety and confusion even after the Baron announced it was safe for everybody to get back to work.

A few days later, reports reached the castle of a desperate family near Dundrum that had put new lands to the plow just the other side of the barrier, and suffered the same fate as the two soldiers: left strung up from a tree practically beneath the ramparts of Dundrum Castle, stripped of everything except the ropes around their necks and wrists, tragic and involuntary messengers and messages all at once.

All the Barons’ castellans stepped up their patrols. Merchants and mendicants avoided traveling—even more than they usually did, in these parts. Farmers who could, sent or brought their families into the crowded castles at night for safety.

But life went on: It had to. Life on the Pale was lived too close to the edge of so many kinds of disaster; they had no choice. Farmers, herders, and the few craftsmen and traders who supported them had to keep caring for their animals, maintaining their tools, insulating their homes, and growing food. For most of them, playing it safe simply wasn’t an option. If they didn’t work every day to put food on their tables and clothes on their backs, they couldn’t survive—even without worrying about human threats.

The children didn’t know it; but this promising, fresh, cool morning was it: the closest any of them had ever been, to the ever-present danger of a cruel death or a crueler captivity.

The edge was where they lived, these children: right on it, as close to tragedy as any of their elders. Closer, because they hadn’t quite wrapped their head around the danger they lived in, and wouldn’t have been able to do much to protect themselves from it if they had. The women of the castle kept them closer than women kept children in most parts of the world, because they had to. Kept a closer eye on them, too. Even so, they couldn’t be vigilant every minute of every day; it just wasn’t human nature. Only the most-disciplined and -cautious among them were alert all the time, usually for reasons (most of the children who survived to adulthood would realize at some point when they were experienced and wise enough) that had less to do with their current circumstances than some terrible past circumstance they would never really be able to get past.

Danger and death were there. Everywhere, just around the corner, just out of sight: hiding in the trench of the Pale, concealed down in the river bottoms, behind the rolling hills of the frontier; and most of all, invisible in the woods and bogs that dotted their borderland.

They were playing “king of the hill” right after breakfast, all the children from the castle. And of course, they were playing it on top of the Earthen dam itself: the defining characteristic of their homeland, and as they understood to different degrees according to their ages and faculties, the raison d’être of their entire community. Of course they had chosen it. Its walls were the tallest and steepest slope they could climb up or tumble down without serious injury; and there was the added advantage, even if none of them was thinking about it in the moment, of putting them within a dozen yards of Castle Shanganagh, meaning the sentry on the roof could keep an eye on them, even if his attention was supposed to be focused further away, near the horizons, scanning them for any sign of hostiles.

It had been two weeks since the Irish letters were left for Shanganagh. The Baron had taken a plurality of the soldiers from Shanganagh, Dundrum, and the other Northern castles down towards Bray, where the O’Byrnes had erupted from their mountain strongholds three days ago to rain chaos down on the English settlers.

So early in the morning, half the castle women were still slow with morning grogginess, all of them huddling near the fireplace in the great hall telling themselves they’d just wait to finish their cold cuts and bread before checking on the children, whose voices they could even hear from time to time through the open castle door. And they could tell themselves the sentry could see the children, and would warn them if anything serious happened. Even if they knew it wasn’t quite true.

The sentries were soldiers. Men. What did they know of children? Nothing. Some of them lacked the common sense God had given even unto the rodents who infested every human living place. Half of them seemed to lack the gene recognizing children as humans at all, let alone the portion best-deserving of care.

The little ones stayed away from Stephen, the castle’s current resident bully, because they knew he was careless and mean enough to hurt them for real by roughhousing with them as if they were five- or six-year-olds. Fortunately for all of them, they lived in a community small enough that children didn’t have or form separate societies of their own though Char would be—for a few blessed weeks afterwards might hurt them for real who would have been a bully in a who they knew would push them as roughly as they’d push the older children; but —until Ollie, as slow and deliberate as he always was, finally finished his food. Always the last to finish, and a good thing too because when Ollie played King of the Hill he always won and the other children couldn’t even dislodge him by ganging up on him

“Pale” came from pālus, a stake used to support a fence. So by extension, Brother Hugh had explained, reaching above and beyond his usual unimaginative and uninspired teaching with an example relevant and meaningful to them, managed to teach them a bit about geography during their Latin lesson. Ironically, their home was named after the comforting if ugly dam of dirt that honed to the castle like an arrow across the landscape around them, from Southeast and Northwest alike. Ironically, because as best any of the children could tell, there weren’t actually very many wooden stakes in it. A few, especially where topography squeezed in forcing the walls to be narrower or sloping terrain increased the risk of erosion. But the walls near Shanganagh, at least, were your basic big-pile-of-dirt. The Baron claimed the barrier stretched from around Bray in the South, in a wide arc inland to Kildare and the remotest reaches of Meath, and finally back to the Irish Sea at Louth. But since anyone could see from the roof of the castle, or a couple hours’ walk, that the earthworks on either side of Shanganagh petered out right about the edges of the richest fields worked by the Baron’s local tenants, only the children believed that story. The Baron didn’t even have enough men at Shanganagh to protect that short length of wall; let alone Shanganagh’s portion of the frontier between it and the next castle in each direction.

After Ollie shoved everybody off the hill, and a rather peremptory probing assault confirmed he was still the master of the game, the children at the bottom of the hill switched to tag and jump rope and playing with the old bladder they used as a kind of football.

The sky was as gray as always. Like a fancy noblewoman from Dublin who hid her own skin every day under a coat of lead that was supposed to beautify it, the thick clouds overhead concealed the intensely emerald island from heaven, too busy nurturing its beauty with water to let it be seen.

And thus, the shadows were long, and deep, especially down in the treeline by the stream.

Not a child noticed anything amiss; any more than the sentry himself. But they were there.

Trolls, elves, hobgoblins, dwarves, and all the other creatures of the woodlands were a constant worry, even without their parents weren’t warning them to be careful outside, even if their parents were pleading with them to stop bothering them with their groundless fears. But from time to time, when the games were away from the treeline and the threat the children were worried about was of Brother Hugh interrupting their games by calling them to their lessons, they forgot to pay any attention to the trees, however close and concealing they were.

It was the shouting of the adults that first caught the attention of the children. And if they attributed the calling to normal business in its first few seconds, that didn’t last long. The strain and alarm in the voices, the number quickly joining the call, and even their locations were wrong: The first cry came from the doorway but the next—belatedly, oh so belatedly—from the parapet of the tower where the sentry stood guard.

“ROBERT!” One of Char’s companions’ mothers screamed. “RUN!”

And then it was several women pouring out the door of the castle, screaming and gesturing at their children to run. Run as fast as they could towards the door. And the sentry on top of the tower, imitating their gesture for half a second, then struggling to load and aim his crossbow.

A couple of the smaller children began to run. Their mothers’ and aunts’ and older sisters’ cries were enough for them: they heard them and heeded them without delay. But the older children delayed.

Not on purpose: by instinct. They frowned in confusion at their female relatives, then turned and looked around them trying to understand what they were worried about. Those who looked up, understood immediately what a drawn crossbow implied: raiders. And close. But somehow, for many of them, realizing there must be scary men threatening them only increased the necessity of setting their own eyes on the threat and quantifying it.

What they saw was a line of men, 6-8 or maybe even 10 in number, running toward them at breakneck speed. Their irregular armor, weapons, and helmets—comparable in their variety and quality to those of the English militiamen—marked them as soldiers.

Their bare feet and legs, saffron Léinte (chemises), and heavy fringed brats (cloaks as versatile as they were warm, the Irish counterpart of the great kilt and arisaidh) marked them as natives: wild Irish in their savage dress, which according to many of the English (who were, perhaps, unfamiliar with the continental, and even English, fashions of the previous century) defied any pretense of civilization.

Kerns: Irish light infantry. Raiders. Reivers.

Upon sight of them, even the most stubborn children screamed and ran, as fast as they could, most forgetting everything else, even their own younger siblings, at the sight of the Irish. If given an opportunity, they probably could have worked out the threat posed by the Irish, readily enough: death or enslavement, if they were caught; even if they couldn’t have explained the details implied by either of those fates. But who could, really? There were a few stories of Norman knights being captured and enslaved by the Irish, only to survive and escape; but not many. If ordinary English settlers had been captured and returned at all, not much was written about them; but it seemed clear captivity was not a fate to be relished, or even brushed off. They certainly, every one of them, grasped that the moment any one of the men’s hands fell on their shoulder or seized their arm, life as they knew it would be over.

The women screamed and urged them forwards with every sinew of their bodies and voices, as if they could physically will them forward or add speed to their flight. The children, once running, ran as fast and as desperately as their little legs could carry them. But their legs were much shorter than the kerns’ and the soldiers’ legs had been hardened by training, hunting, and campaigning; and they rapidly closed the gap on the children.

Sindonie, one of the more-sensible women at Shanganagh, and her mother Lady Parnell, began shoving other women back inside the castle, realizing that when the children reached them there was a risk of a traffic jam in the final few seconds they needed to be closing the door and throwing the bolt. The other women, still screaming at the children, darted their eyes back and forth between the children and the kern, gauging their speeds and distances, trying to know what would happen; trying to will the children to make their escape in time. Through the door, the children could see one calm Wrathdonian soldier kneeling calmly 2 or 3 feet inside the tower, resting his drawn sword over his knee to be ready-to-hand, and tipping his crossbow up so the bolt would stay in place without risking an accidental shot through the women and children. But most of the men would be heading for the roof or the arrowslits in the upper floors of the tower: Much better positions for defending the castle itself; and perhaps theoretically for defending the children except that by the time most of them could hope to be in play the childrens’ fate would already be determined.

So it came down to them, their scared female relatives, and the sentry on the roof who had given every indication so far of being incompetent, inexperienced, inattentive, or all three.

In fact, the sentry did get off a shot, just as Rash Henry reached the roof close enough to its rear parapet to see what was happening below: A shot that fell far short of the kerns he was trying to kill or delay, falling instead right in the middle of the children. More specifically, whistling into the dirt less than a foot in front of a well-dressed boy with long blonde hair Rash Henry recognized with shock as his younger brother.

It would be fair to say none of the Wrathdown children enjoyed the kind of friendship most parents might hope for among children. Indeed, Baron Wrathdown had done almost everything within his own personal capacity to ensure the children lived at one another’s throats, aware they were rivals in everything and that their father at least viewed them as such. Practically as replaceable, potentially-fungible commodities he was more interested in grooming and using as a pool of candidates for the top management positions in his Barony, rather than as individuals with personal meaning to him.

And none of Char’s older brothers had a good word to say about the youngest. Even before Sindonie had commenced her devastating work, they had viewed him as spoiled and coddled primarily because he was the youngest, and there hadn’t been a pile of younger siblings behind him to compare him with and demonstrate he was just another chip off the old block. After several months in Sindonie’s care, he was finding himself to be very, radically different from his siblings or his father, and not interested much that interested them.

But still—this was his brother; and even if Rash Henry didn’t like him, he felt the affront to his brother was equally and personally an affront to him, and to all of the Wrathdown name. His stream of profanity was lost on the children and women below, even Char, who were too wrapped up in their desperate circumstances to pay much attention to the roof anymore; but the sentry blanched at his threatening words and the violence with which he wrenched the man’s crossbow up and shoved the man back against the parapet, nearly making him lose his balance and fall over it to land on or among the women standing below.

Char’s consciousness flared with sudden awareness of the bolt plunging into the soil nearly literally under his feet but didn’t have time to dwell on it yet. Certainly, from its angle some part of the child must have recognized it hadn’t come from the Irish. And fortunately it didn’t trip him up or cause him to stumble; he washed over it like a wave, behind one child and ahead of another, running and yelling without thought for his dead mother, probably thinking at least in part of Sindonie.

For every foot the children covered, the kerns covered two or more; and a moment later they were among the children, snatching up two little boys and a little girl who were straggling, just as the first of the children raced through the castle door and Sindonie, beside the doorway, raised the Baron’s arquebus. A keening scream from inside the tower was presumably one of the mothers whose child had been seized, catching sight of their fate, but events were moving too quickly to process them let alone dwell on them.

The men pouring onto the roof above roared in dismay as they noticed kerns leading a cow and a horse out of the barn, focusing their attention on them and firing a scattered volley of a few arrows that failed to find any of the kerns; but mercifully weren’t anywhere near the fleeing children whose plight the soldiers were ignoring, distracted by a wisp of smoke from the barn’s thatched roof and the potential loss in livestock. They did frighten the horse, which bucked off the hand of the kern trying to mount it, and—with a minor but apparently painful scrape on the rump—stampede the cow, who was later found eating grass beside the Dublin road with a broken arrow stuck in her tail.

Ollie fled past his mother a moment later, looking worried but knowing better than to mess up the retreat by blocking the door; immediately followed by the mass of the children. A few moments after that Char and Edith, the last of the children not yet captured, who had been skipping rope away from the other children playing tag, trailed past after the others, clearing Sindonie’s line of fire just as the closest of the pursuers looked up at her, shouting as much in surprise as fear and instinctively turning away, crashing into the second pursuer and slowing all of them down just as Sindonie fired.

Whether she had scored blood or not, she never knew; it was the first time she’d fired an arquebus, and she considered it a victory that she’d managed to ignite the gunpowder. Doubtless, had the men given it any notice, they would have compared her level head favorably with that of the sentry who had nearly shot the Baron’s own flesh in his haste.

In the seconds as the men checked themselves for injury and turned back towards the door, Sindonie fled through it, pulling it shut behind her and hearing the two heavy crossbars slam shut, thrown by two of the older women who had been waiting for the opportunity. Char practically jumped into Sindonie’s arms and Ollie hugged her fiercely, all three of them talking over one another as they expressed their overwhelming feelings of fear and relief to one another.

Around them, other women were hugging and holding their children fiercely; and a couple of the older women were physically holding the mother, or one of the mothers, of the lost children: at first to keep her from throwing the crossbeams off the door and hurling it open in a doomed effort to recover her child; then to keep her from falling over, as she suddenly seemed to lose her strength and sag towards the floor, wailing in horror.

The kneeling crossbowman rose to his feet and helpfully took the arquebus from Sindonie before she could drop it; then looked up toward the top of the stairs, looking or listening for something that apparently persuaded him not to follow the other soldiers up to the parapet.

Instead, he returned to the door and cautiously peered through a slight gap where a knot had deformed a piece of wood just enough for light to show between the two boards. Apparently whatever he had seen, or not seen, reassured him because he shouted towards the top of the stairs: “Is it clear?” And when he received no response, he repeated even more loudly: “IS IT CLEAR YET?! Is it cl—”

At that moment four soldiers clattered back down the stairs having come, presumably, from the roof; their leader crying: “Wait for us! It should be clear but wait for us! Men!” and here everyone recognized he was talking to the older and poorer men, unarmed or holding hoes or scythes or other farm implements. “Follow us! Grab the buckets in case the barn is burning!”

Everyone in the main room reacted to that; fire may have topped the long, long list of things the Englishmen of the Pale feared: Irish, Baron Wrathdown, famine, flood, pestilence, plague, flux, scurvy, pox—fire. Fortunately, it was wet outside, the castle was stone, and there’d been plenty of rain. But still, the barn was close by the castle; and the four upper stories had wood floors, wood furniture, and wood internal walls; supported by wood beams and columns. There was plenty to burn inside the castle, basically everything except the fireplace and the wooden shell of the building around them, which would look more and more like a flue as the wood burned or fell down inside it. If the fire got inside the building before they got out, their lives would be in mortal peril.

Rash Henry would explain to all who listened in the coming days, how he and the men under his command had stoutly defended the barn, driven off the kern (who indeed, hadn’t taken or damaged any of the livestock), and “saved” the barn by stomping with their boots on sparks and smolders in the wet, fouled hay in a corner where the kerns had dropped a torch.

But that wasn’t what most of the people at the castle would remember about that day. Two fathers and one mother (Sir Edmund, the father of the two lost girls, was a widower) had lost children; and while they were especially devastated by the losses, everyone felt them. There weren’t that many English families on the Pale; and with the exception of those desperate people drawn to this harsh world by the economic opportunities warfare and chaos offered, they tended to be families that had been living on the edge and battling the Irish for generations. Families on the Pale were like a hedge of briar bushes, prickly and entertwined with one another, even their stalks sometimes grafted onto one another’s roots; and virtually everyone at Sanganagh Castle was related to the missing children in some way, as a distant cousin or recent in-law at the least.

All of them who had heard the children’s screams as they were seized, would remember the sound the rest of their lives; many of those would hear it echoed in terrible dreams over and over and over again. The mother who had watched her son’s face, seen his hands reaching out desperately for his mother as he was taken away from her, would never even be close to the same again. And Sir Edmund… would be forever changed as well.

Some said they’d been under-defended, or that the Irish had successfully baited most of the castle’s defenders away, leaving them vulnerable. But nobody thought it wise to share opinions too openly, that could be interpreted as criticisms of their leaders.

Literature Section “08-1.5 Edgeplay”—more material available at TheRemainderman.com—Part 1.5 of Chapter Eight, “The Wild, Wild West”—4295 words—Accompanying Images: 4870-4879—Published 2026-02-04—©2026 The Remainderman. This is a work of fiction, not a book of suggestions. It’s filled with fantasies, stupid choices, evil, harm, danger, death, mythical creatures, idiots, and criminals. Don’t try, believe, or imitate them or any of it.