CAUTION: Contains themes of rough bondage, graphic nudity, and medical procedures some readers may find disturbing.

Unabridged versions of images containing rough bondage, graphic nudity, and medical themes at 08-5X The Defiled Confinement of the Scáthach at Patreon.com/TheRemainderman

A dark, moonless night. As it must be.

In a dark, trackless forest. A forest greener by day and more alive by night than any English forest. Any civilized forest.

And deep, deep within it, a dark old cabin.

Inside that, something even darker; deeds and portents like to draw away what little light and breath otherwise might have been drawn here.

And in a rough old wooden bed, a woman lying on her back, bound and in agony.

Her arms and legs were lashed to a rusty old iron bar above her head; a bar she gripped hard and tightly enough to make her fingers turn white and her arm muscles shudder with exhaustion. A bar that raised and spread her ankles, trapped by heavy black stirrups tied to the same iron bar, in a position far too high and wide for any humane comfort.

Her skin was wet with blood, from 187 shallow cuts into her flesh marking out bloody blasphemous profanities. Everywhere: her stomach, her breasts, her back, her shoulders, her arms, her hips, her buttocks, her legs, her hands, her feet, her neck and head.

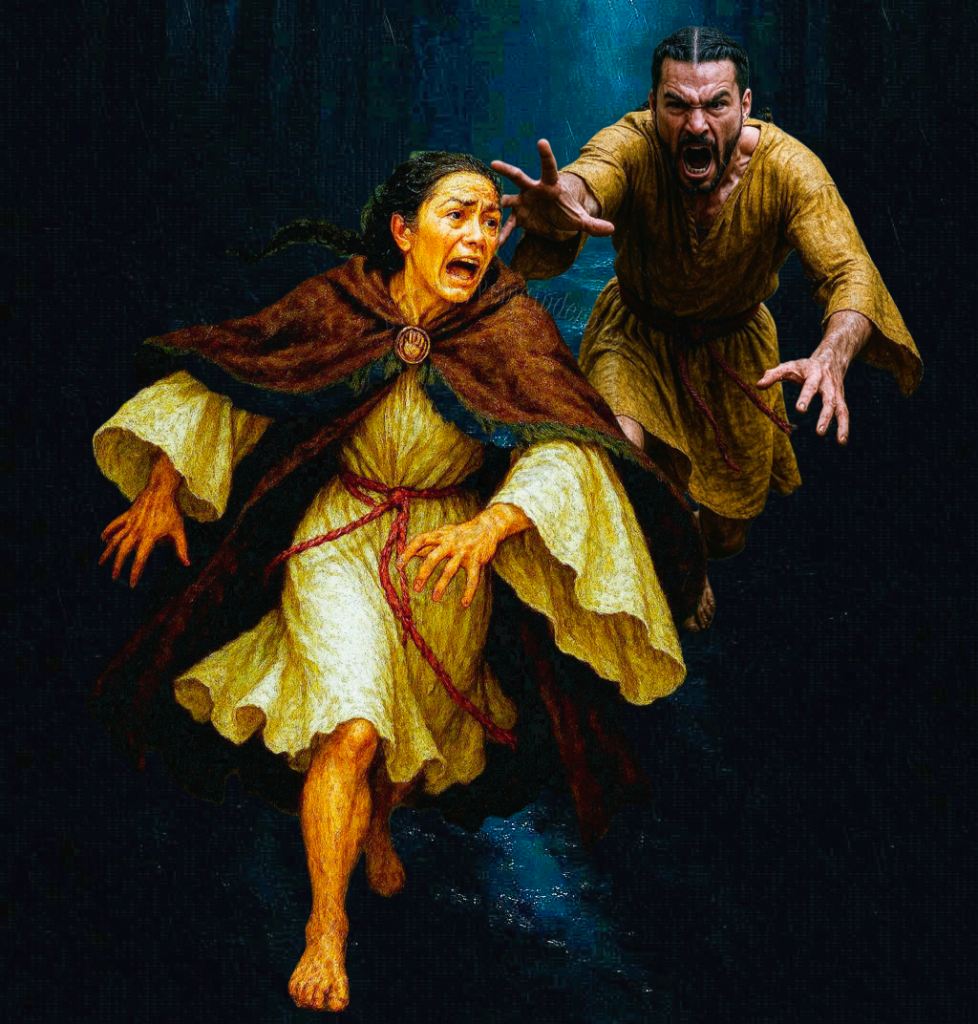

She was screaming.

Screaming and thrashing, her muscles animated with more force than direction, kicking and flailing and writhing for the sake of moving and exerting themselves rather than in an effort to reach anything or accomplish any movement through space.

As if a normal childbirth, attended by sympathetic or at least professional assistants focused on your and your baby’s well-being, weren’t difficult enough for a woman: Try pouring on magic, coercion, and what surely no one would be surprised to learn was a she-woman’s sizeable serving of hell, as oil sprayed on a fire, and it would describe something approaching the torture this mother was suffering in this hopeless, embarrassed place.

The only light came from the spell and its components: The glowing magic circle on the floor around the bed; the ripples in time and space created by magic that manifested to most humans as hallucinogenic sparks, swirls, and even symbols of light. Ripples that by their nature, gave the impression of bursting forth from the slowly-opening vagina of the wretched female in the bed, its beams growing brighter and wider as her sex dilated and dilated and dilated to the proportions of her stuffed womb in her huge pregnant belly: to proportions even the sickest artist or criminal couldn’t have imagined without the example of nature, distending into something like the maw of a sea monster, further poisoned by the blood flowing there, that had nothing to do with any marks or spells except those of cruel nature. Blood: a sure sign of injury, a literal red alarm warning the primal human mind of danger and the need to push a body to its limits for the chance of survival, a clanging klaxon remorselessly demanding one’s highest attention to the cause, the supreme mission, of making the flow of blood STOP.

But here it was ignored, accepted, taken for granted.

Here, the horror was only beginning as her pudenda kept distending, to an extent her jaded old husband—for all his vile fantasies and desires—had never dreamed about, and he would just as soon never have seen. Even the hardened old crone beside him, an ingot of steel compared to the hardest heart; and the demon-king himself, a shimmering vision teasing and mesmerizing the eyes into imagining him shifting back and forth between his human and dragon forms, looked disconcerted by the drama unfolding so appallingly on the bed before them.

She was thrashing and kicking like one being disemboweled or impaled.

Thrashing and kicking and—screaming.

Last and fifth present was the mage: herself a demon, a demon even other ugly, unnatural demons considered ugly and unnatural. She wore red hide more than skin; a face more like a serpent or a pig than a human; and a body more masculine than feminine. Her hands and mouth worked continually, her entire body swaying as she drove the spells swirling and penetrating the woman on the bed and the things inside her. The mage’s voice rose, and with it, even her hands seemed to stretch higher and higher, wider and wider. But her cries were never as loud as the woman’s screams. And her hands were never separated as wide as the huge hole dilating open in the middle of her spastic subject.

When it came, it tore her apart: ripping her flesh with such violence the child shot out on a residual, sudden flush of blood and amniotic fluid like the demon’s own backbirth. The demon-god beamed and applauded, all happy with what he had received, caring nothing for the woman, who was just a vessel as far as he was concerned; and little enough for the feelings of the baby, because gods did not have feelings the way humans did.

The vile husband looked down with an expression simultaneously horrified and aroused, and the crone’s eyes remained fixed with the same predatory expression they always held: alert, attentive, never resting, always looking, always assessing and evaluating.

The complete disintegration of the woman in the bed, further and gruesomely decorated with an explosion of blood, registered like anything else on the crone’s hard eyes, simple data points. Emotionally, they seemed to mean nothing to her. Even the Mage, who one might have expected to be hardened by a lifetime of magic, had to struggle to stay focused on chanting her spell properly; and her eyes glazed over as she deliberately unfocused from the physical trauma around her, sending her consciousness deeply into the process before her, to hide in the logic and deadlines of it all, where the horror could not quite find her, only haunt her with the knowledge it was actively stalking her.

The demon flew upwards, sprays of blood arcing from its wings as they began to flap and its throat to scream, a piercing sound that put off the husband and the crone; and almost buckled the mage in mid-chant.

As the demon disappeared in a flash (either its own, or that of the demon-king departing with it,) darkness mercifully descended on the room around them, concealing the horror in the bed, death and life all left behind in a muddle. The woman—dead. She was, she must be, dead. Her body had been torn asunder.

But her child shrieked, announcing its arrival as a strong and healthy baby which the mage tried to signal with her eyes to the couple across from them, ought to be picked up and swaddled. Immediately. The mage could not do it because her more-important job, the one on which all of the lives in the room or departed from it depended upon, still called upon almost every one of her faculties, definitely including her hands and arms as they continued to weave and stitch, a dance in the air healing space and time themselves, returning them to their natural, or at least their stable, states. Apologizing to them, to their spirits, for having disturbed them so badly in the first place. Protecting and nourishing the child left behind. Treating both its umbilicals, the one to its mother and the other to its demon.

Certainly, she could not be healing the dead. Repairing them? Resurrecting them? Or restoring them to a state she had once occupied but plainly, categorically, rejected and left behind? The mage wasn’t even sure there was a name, for what she was trying to do. Or undo.

Hauling the mother back from the dark sea, with the half-foot hook—more of a claw—required for the largest and wildest sea creatures who were ever captured instead of capsizing or destroying the ships that tried to constrain them, was a process every bit as brutal as the murderous demon-child that had banished her from this plane in its monstrous coming-forth. The husband and crone looked doubtful that bringing the woman back was even worth it, if indeed it proved possible at all. Had it been up to them? None of them would find out what would have happened then. Because the mage had given her word—reluctantly, under the strong protest of her feudal lady, but given it nonetheless—and she was determined to do everything in her power to prove it.

That was quite what was required, every ounce of her energy, every jot of her power, and every wit in her head, to try and deliver all that she had promised. Her resources and efforts were the only things that could have had any hope of bringing the woman back and putting her back together again, a responsibility the mage took seriously.

But hope was different from certainty: Something came back, to be sure. Presumably (hopefully?) someone. But inevitably, the soul that came back brought back such scars, inflicted on it by the event of its banishment, that it could hardly be recognized as the same soul that had once inhabited here.

Wounded soul or hellspawn? Veeerrry difficult to know. Because, on the one hand, such a soul would be so injured, and (in the case of a soul like hers) colored and perhaps twisted with so much forbidden knowledge she would understand the threat posed by the deep suspicions of the powerful druí before her, and who would be determined to persuade them by any means necessary that she was who they wanted her to be. Or, at least, who the Mage wanted her to be. And on the other hand, such a demon, from such a depth of hell as the mage had called upon tonight, would be so cunning and eager to deceive one would scarcely be able to tell it apart from the soul it had gobbled up in hell and sought to pass itself off as, here.

It may have been vanity alone that ever persuaded a human she or he could tell whether a soul had been rescued from hell, replaced with hell’s creature from it, or reduced and twisted by it, in the uncertain time it had been away from its body. Time in hell moved so differently than on Earth, living mages had no way to even estimate how much time had passed for a soul in another dimension unless the soul told them and they believed it. And as if that weren’t enough, certain demons were known to have ways through time and space no human could follow, let alone measure.

But in the end, it can be said, there were five of them left in that room; just not which five they happened to be. The husband and crone appeared as cold and unmoved emotionally as ever, but moving with their bodies to light candles in the room once the things that could not bear light were gone, and then eating their dinners without lifting a finger to help the rest of them. The babe, as it appeared to be, was cleaned, swaddled, and placed in the mother’s arms by the Mage as soon as she could do so. The mother, or whatever might be animating her arms, lay appearing to comfort the child. And the Mage, simultaneously comforting the woman to help her return as close to intact as she might; and evaluating every action, word, and expression from the mother’s reassembled Frankenstein body looking for any hint of deceit.

UNABRIDGED VERSIONS OF IMAGES AVAILABLE AT patreon.com/TheRemainderman

Literature Section “08-05 The Defiled Confinement of the Scáthach”—more material available at TheRemainderman.com—Part 5 of Chapter Eight, “The Wild, Wild West”—1900 words—Accompanying Images: 4613-4615, 4613-4615—Published 2026-02-02—©2026 The Remainderman. This is a work of fiction, not a book of suggestions. It’s filled with fantasies, stupid choices, evil, harm, danger, death, mythical creatures, idiots, and criminals. Don’t try, believe, or imitate them or any of it.