The Earl’s daughters were already starving for love and support after losing their mother. But as sometimes happened, fascination with their stepmother seemed to eclipse Lord Robert’s interest in his own children. The new Countess, famous for her work with orphans, was as interested in the girls as their father was disinterested. But her interest—contrary to her reputation—was punitive and vindictive. She seemed to go out of her way to magnify the disruptions in their life, communicating as forcefully as possible how unwelcome they were in their own home. Although she could be a harsh, even vindictive disciplinarian to her own nieces and nephews, she also showed a warmth and fondness toward them completely at odds with her unrelenting, frosty hostility towards her stepchildren.

Talk of the remaining Defalais girls’ weddings, and even betrothals, soon sputtered into silence, replaced with dark hints and suggestions of futures in the nunnery. It was decided that unlike their stepmother and stepsisters, the girls already had plenty of dresses and gowns to last them indefinitely, however they might compare with debutantes of lower standing—or even girls of lower classes. Their education—something their mother had fought for and encouraged them in, something that made them identify with her even as it helped define their identities—was deemed wasteful for girls.

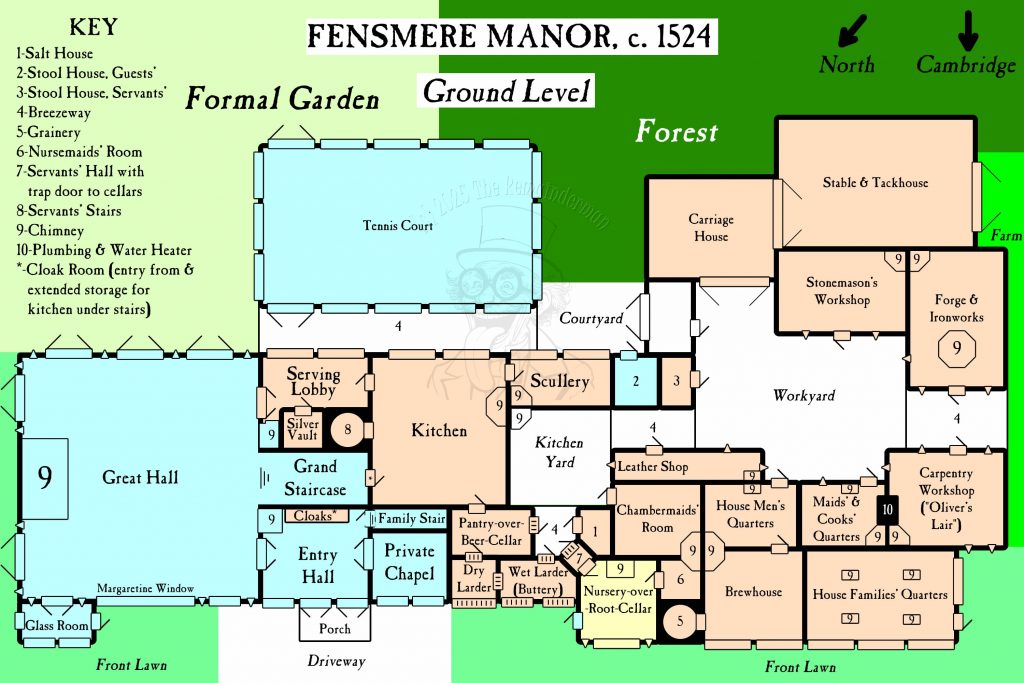

The girls’ governess—a close friend of their mother’s, who had been governess of all the sisters since Margaret the Younger had outgrown her nanny—was sacked for laxness, literally chased off across the front lawn with a broom by the Countess, huffing and gasping and staggering away as fast as she could while her former charges wept and pleaded uselessly on her behalf. She was summarily replaced by Sindonie Manning, the longtime governess of her own wards, who at least showed them the same kindness she showed their stepsiblings.

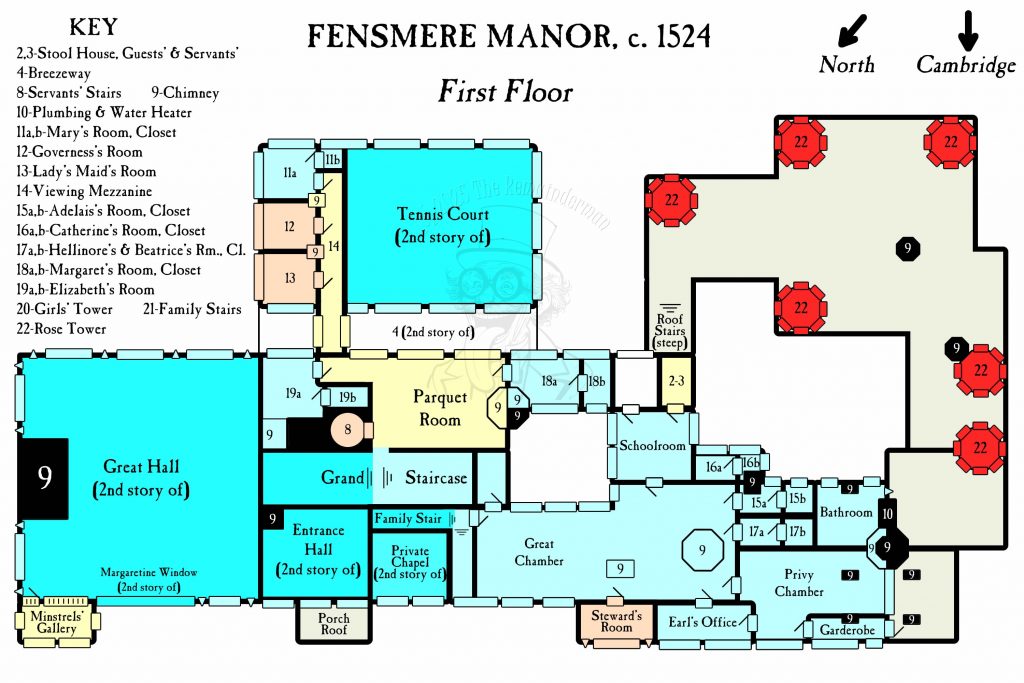

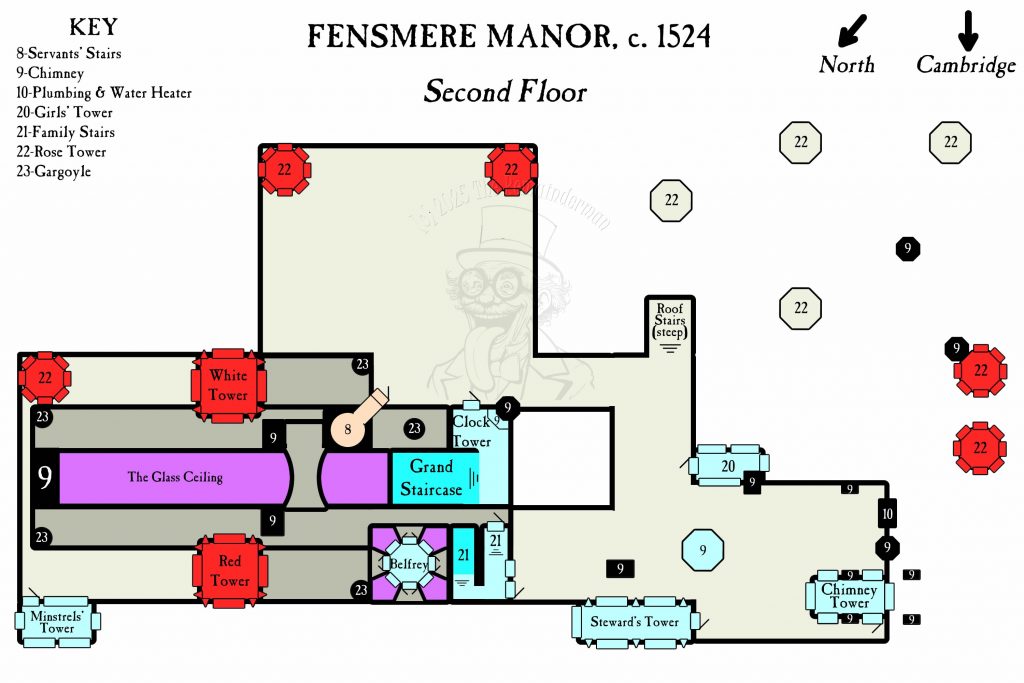

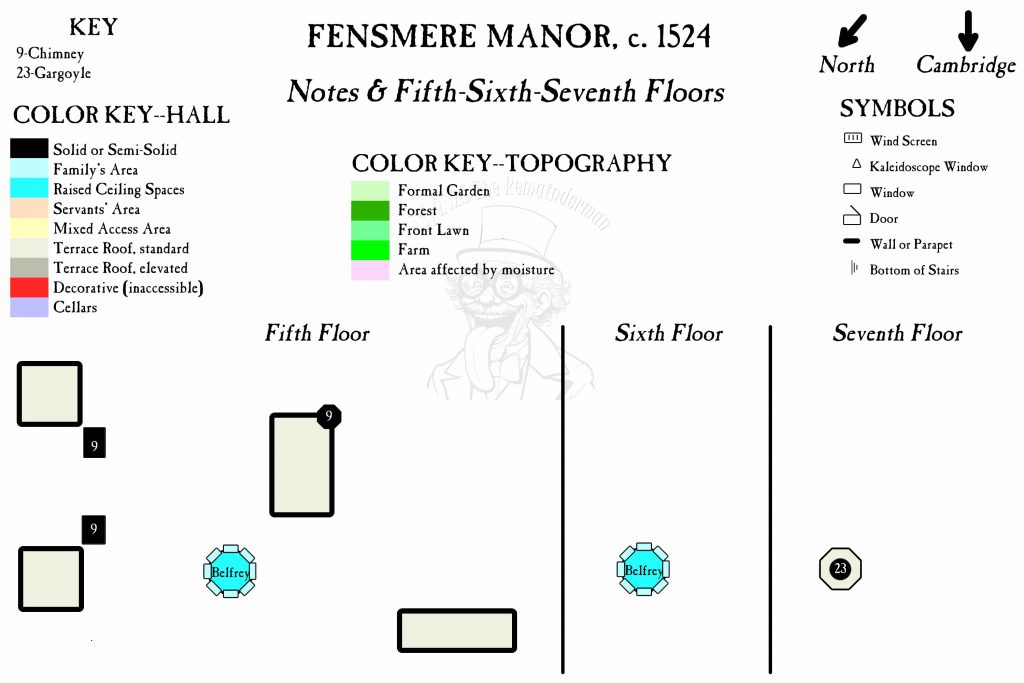

The prestigious tutors also disappeared, their duties to be fulfilled as well as possible by Penance, one of their new stepsisters. Not only had their stepmother decided she would be perfectly adequate to cover the subjects she considered appropriate for young ladies, but she thought it inappropriate for young ladies of their social standard to be socializing with men, especially younger men born into more vulgar classes of society. Since a young student from Cambridge was seen visiting the house, even after the tutors were fired, the girls—and their governess—suspected he was teaching Penny what she was supposed to teach them.

Fortunately for the sisters, Penny was as dedicated to her students as she was conscientious about her duties. Although she was the same age as Catherine, the middlemost of the seven sisters, Penny became a bright spot in their lives, a way for them to feel connected with their mother, and a source of encouragement and support in the face of their father’s lack of interest and their stepmother’s unremitting hostility.

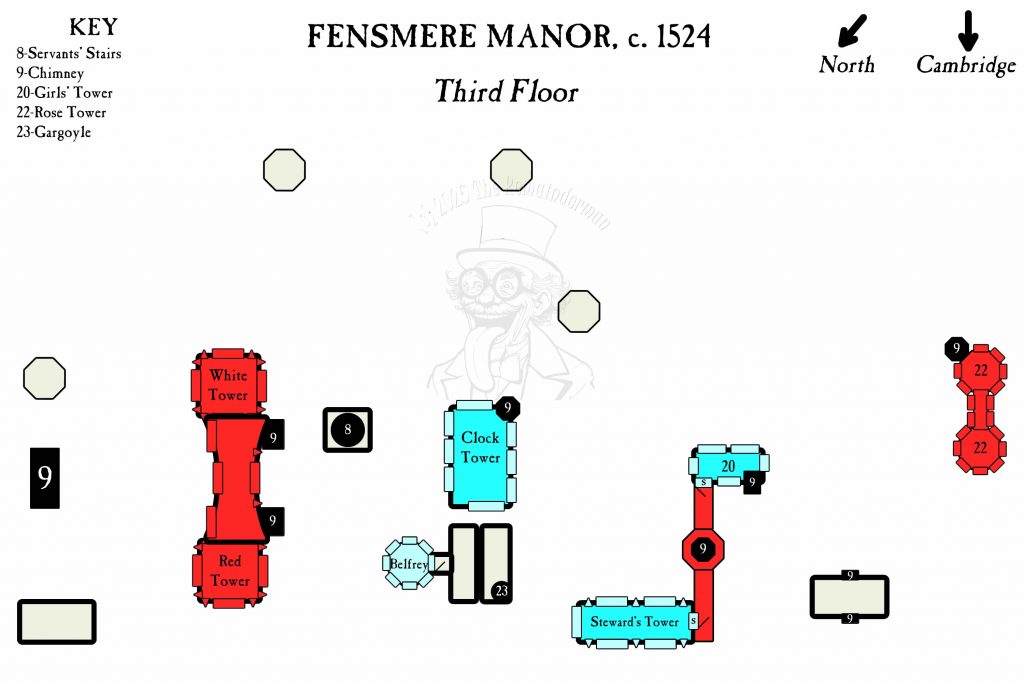

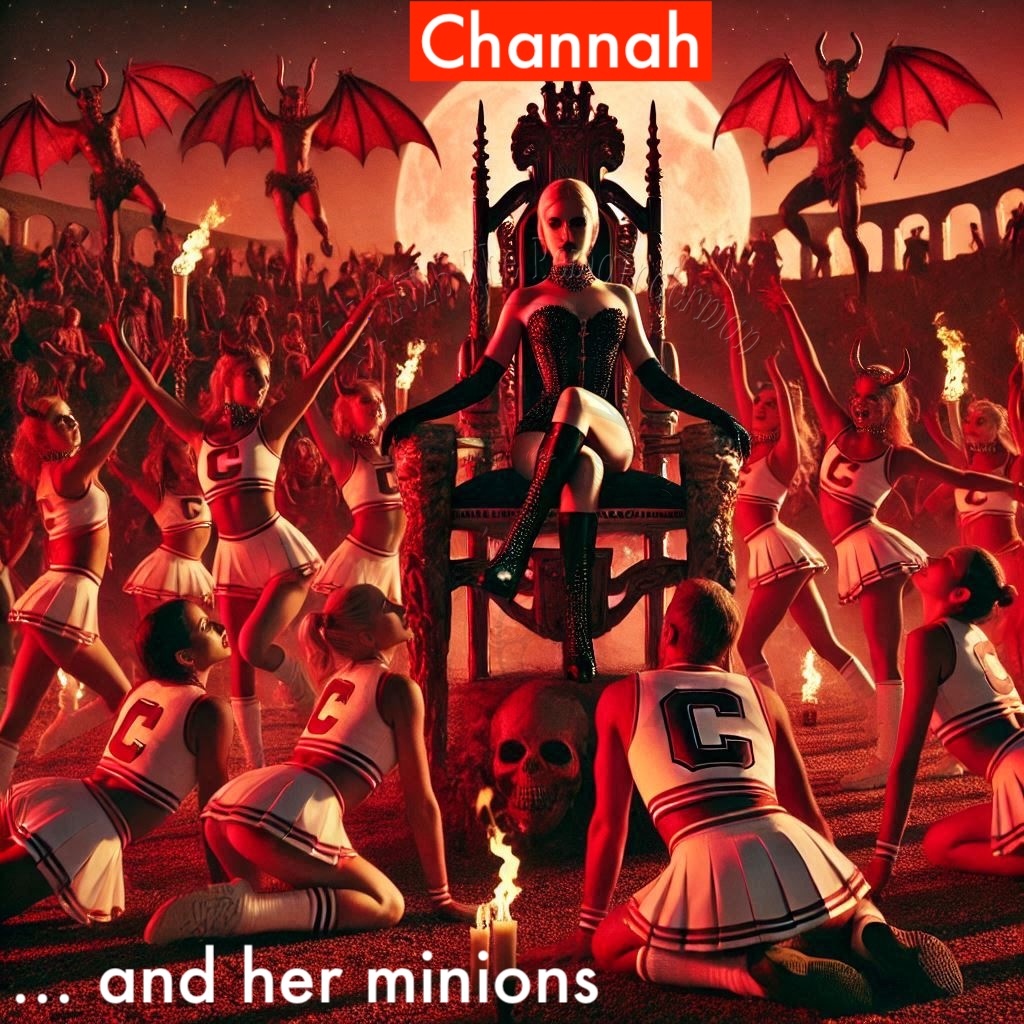

She became particularly important as an anchor for the youngest daughter, Hellinore. Hellinore, although studious and accomplished, had tried even her parents’ patience, earning the nickname “the Hellion.” With the Countess… from practically the moment the two were introduced, sparks had more than flown—they had exploded! Anne Batonnoir didn’t spare anyone under her control the fury of her punishments; and the daughters had to suffer their detentions in their closets. Hellinore, in particular, seemed to spend half her existence with a bottom nearly as angry as she was, memorizing every little detail of her closet, until Penny, feeling sorry for her and guilty, started bringing her books and candles and even teaching classes there instead of the nearby schoolroom, so that she could be included. Her sisters took the change in venue with remarkably little complaining, knowing all of them shared a common enemy, and the only difference among their punishments was of degree. In truth, her older sisters might secretly have been relieved Hellinore acted as such a lightning rod for their evil stepmother’s attentions.

She seemed to be able to take it, for one thing—unlike Adelais, who wilted and shattered when she drew the Countess’s ire. One night, Adelais never came to bed, caught in the clutches of their stepmother. Whatever Adelais had experienced, she refused to say; but she was never quite as bright or gay as she had been before. While Adelais curled up and shrank, Mary became careful and neutral; Beatrice insistently cheerful and helpful; Catherine sneaky and resentful; and Hellinore… Hellinore became a terror to anyone small enough or—a category encompassing most everyone on the Manor—lower-ranking and weak enough she could bully.

Like his daughters, the Earl failed to thrive and bloom in his new wife’s garden. Instead, he appeared increasingly listless and withdrawn; even prematurely aged. Some joked, carefully, that it was his new wife’s energy; but most attributed it to vinegar and tragedy. In some corners, surely far from Fensmere, jokes were made about someone called the “Earl of Quickjack,” but this one, at least, didn’t show the same signs of vigor that had been so loudly proclaimed at his wedding.

PART 2 OF STORY RECAP

Literature Section “06-35 Grimm Transformations II: The Long Fall”—Accompanying Images: 1508-1512. 846 words—©2025 The Remainderman. This is a work of fiction, not a book of suggestions. It’s filled with fantasies, idiots, and criminals. Don’t believe them or imitate them.